How to make the data and code for your manuscript available to peer reviewers ‘before’ making it public

It’s no surprise to any internet user that the way we communicate is rapidly changing. For example, in the distant past, we learned the news of the world by reading a few paragraphs of tiny text in hard copies of newspapers. For especially newsworthy events we got a black and white photo or two. Nowadays, we are accustomed to news websites that transmit distant events to us with full color video, images, infographics, and a stream of live tweets. Just as news broadcasting is changing, so has scholarly communication.

One important way that scholarly communication is that the PDF of the journal article is no longer viewed as the full and final report on a scientific finding. Instead, the PDF is increasingly being regarded as only advertising, or the tip of the iceberg, of the real science. In many research communities there are now expectations that researchers will make available the data files and code files (for example, R or Python code) that were used to generate the published results (i.e. the plots and tables in the paper). For many researchers, the real science is the paper plus the data and code. This bundle of files is also known as a ‘research compendium’. In this post we describe how to privately and anonymously share a research compendium to peer reviewers for double and single blind peer review.

One challenge in preparing a research compendium to accompany a paper for publication is how to ‘blind’ or anonymize it for journals that do double-blind peer review. Double-blind peer review means that the authors don’t know who is peer reviewing their paper, and the reviewers don’t know the names of the authors of the paper they are reviewing. Preparing just the manuscript for double-blind peer review requires careful editing. Many journals instruct authors to remove their names from every place in the manuscript where they might disclose their identity. This includes replacing self-citations, removing identifying details from the data availability statement, acknowledgements, etc. It can be a challenge to perfectly anonymize a manuscript, especially in small research communities where most people know of each other’s work.

But when we upload our data and code files to a trustworthy repository, such as osf.io, zenodo.org, etc. how can we similarly make our materials anonymously available to peer reviewers? We actually have two challenges here: first, how to present the repository anonymously, and second how to make it available to peer reviewers without making it fully public (this may be desirable even in a journal doesn’t require double-blind review). Because these are such new ways of working, and involve new technologies and concepts, instructions for doing this are hard to find. So we thought it would be useful to sketch out how to do this in this post. These instructions are based on our experience with widely-used repository services such as osf.io, zenodo.org, dataverse.org, and figshare.com, and will be suitable for any journal.

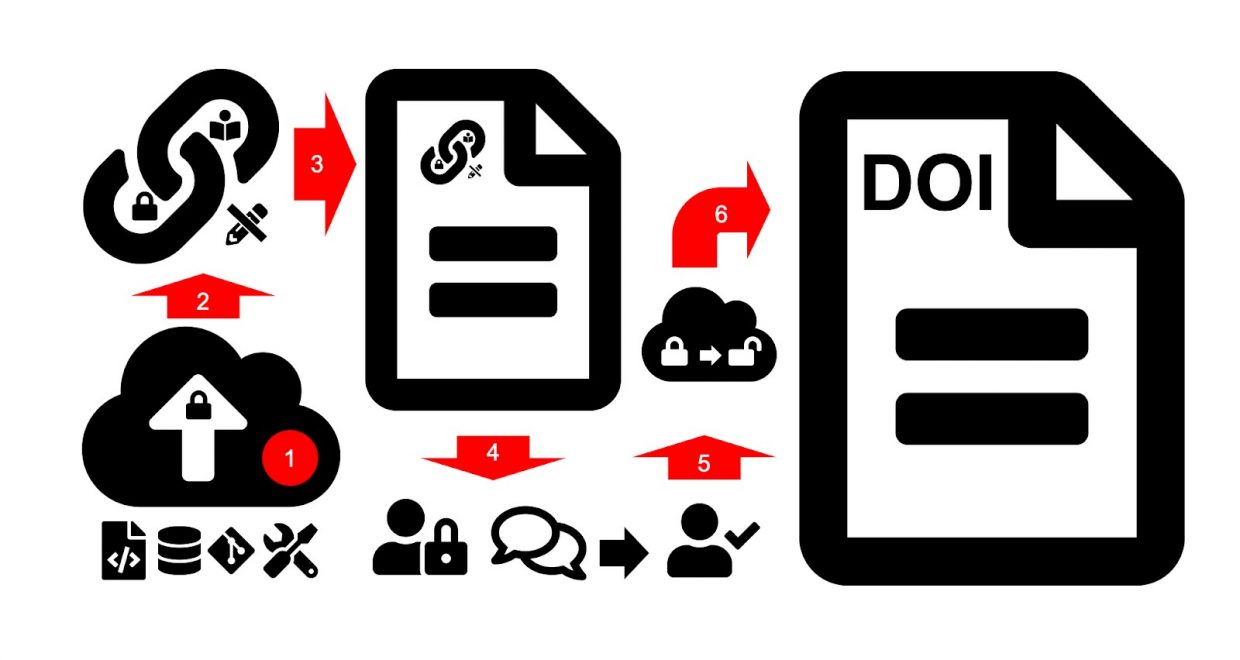

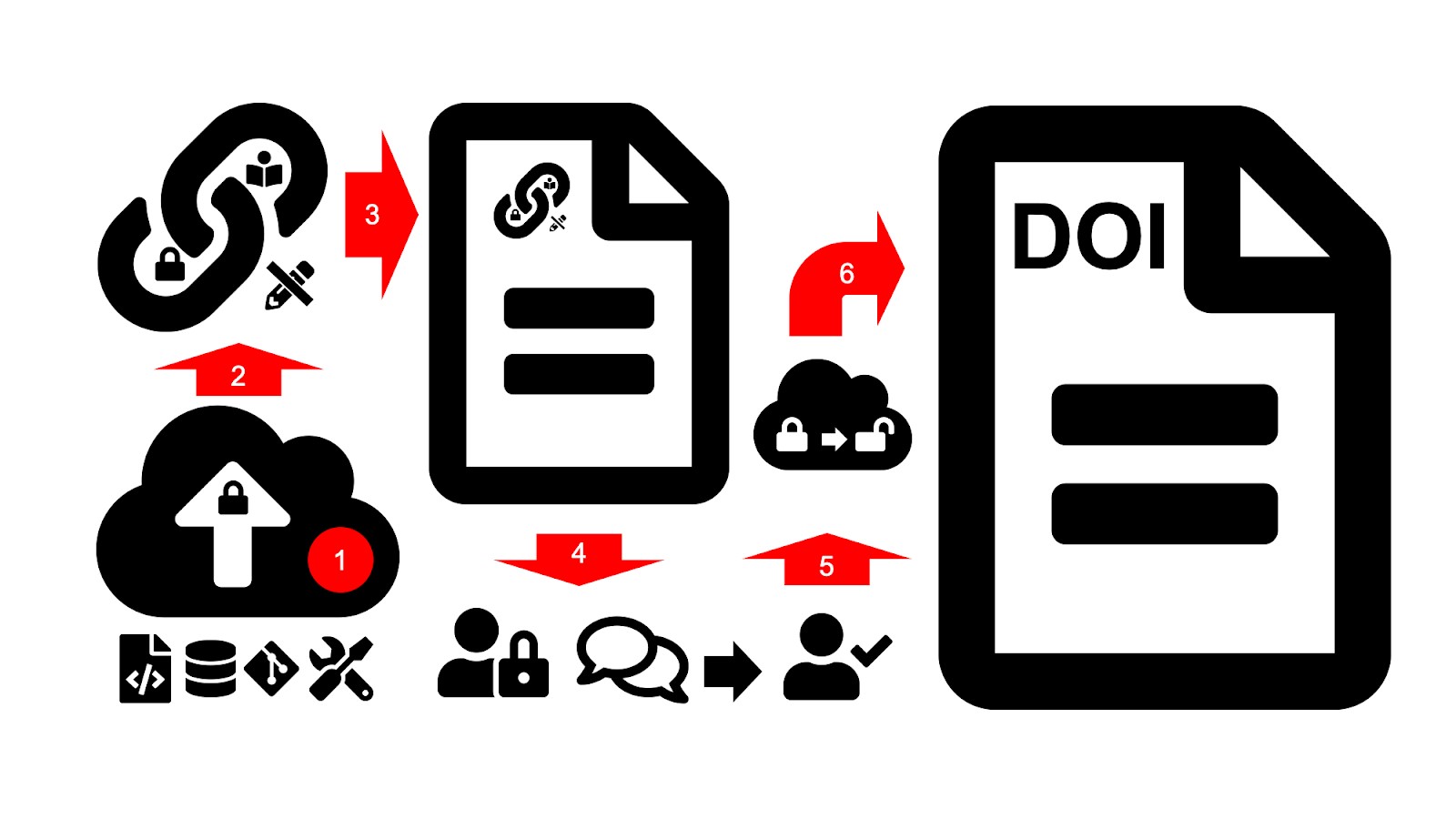

Here are the general steps for preparing a research compendium for peer review:

- We (the authors of the manuscript to be submitted for publication) deposit our data, code, and other supporting files in a private repository while we are finalizing our manuscript, before submission. A private repository means a repository that is only accessible to the owner of that repository. At a later stage we will change the settings on our repository to make it public so anyone can freely see it, without needing an account or our permission. To ensure anonymity for double-blind peer review, we manually review the documents and files that we upload to the private repository to remove our names from them.

- On our private repository website we obtain a ‘view-only’ link from the settings. This special link will give access to our private repository in a way that hides the repository metadata (i.e. our names and affiliations). The repository remains private; only the authors and people they give the ‘view-only’ link to can access it. People with the ‘view-only’ link cannot modify the contents of the repository

- We include this special ‘view-only’ link in our manuscript, for example in a sentence in the methods section that tells the reader that our data and code are available on repository, or in the data availability statement.

- We submit our manuscript to the journal peer review. Their data remains private on the repository. At this point, anyone with the manuscript, such as the editor and peer reviewers, can click on the ‘view-only’ link in the paper to download the research compendium. The peer reviewers can anonymously inspect the data on the repository, and they do not see the names of the authors on the repository.

- Once our paper is accepted, and we are finalizing the edits before sending it back to the editor, we change the settings on our repository from private to public.

- The final step, now that our repository is public is to obtain a DOI link from our repository, and remove our ‘view-only’ link from the manuscript, replacing it with the DOI. Using a DOI link (or similar persistent object identifiers, less common ones include ARKs and handles) in the final copy for publication is very important because the ‘view-only’ links typically auto-expire after a few months. On the other hand, DOI links are a special kind of link that comes with commitments to long term availability of the materials it links to, so these are most suitable for linking to data and code files in publications.

Figure 1. A schematic of the key steps for making a research compendium privately viewable for peer review. The white numbers on red backgrounds correspond to the numbered steps in the text. Icons used under license from FontAwesome.

The steps above will ensure that our research compendium is available only to editors and peer reviewers, and without our names visible to them. This helps us to fulfil requirements to make data and code available, while at the same time honouring the double-blind peer review process.

For further information about the specific implementation of these steps, we can study the documentation of the repository services. We know of three widely-used, trustworthy repositories that have excellent documentation for these steps:

Other repositories, such as discipline-specific services like tDAR for archaeology will have similar instructions (and if you can’t find them, email the service to ask for help).