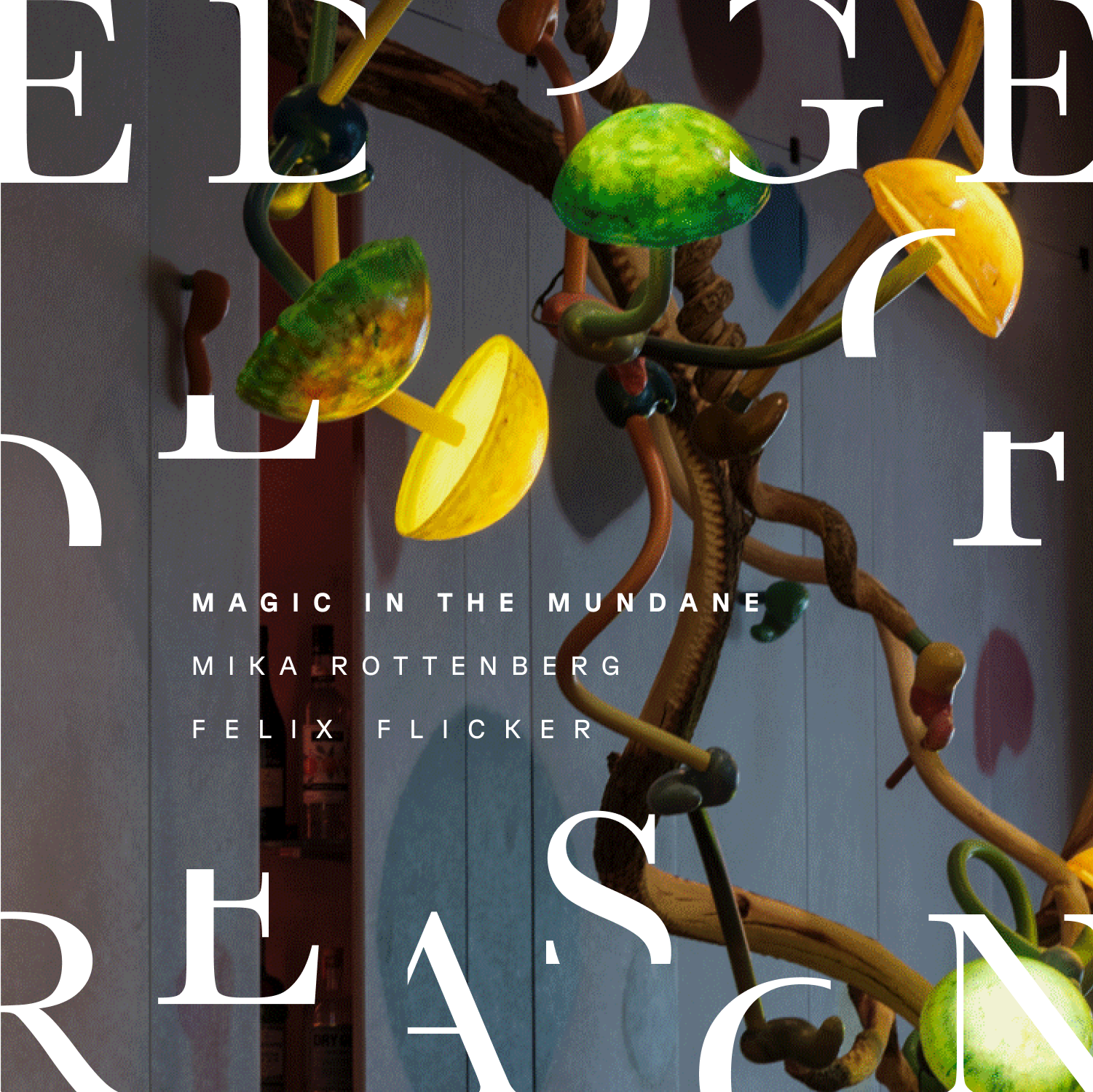

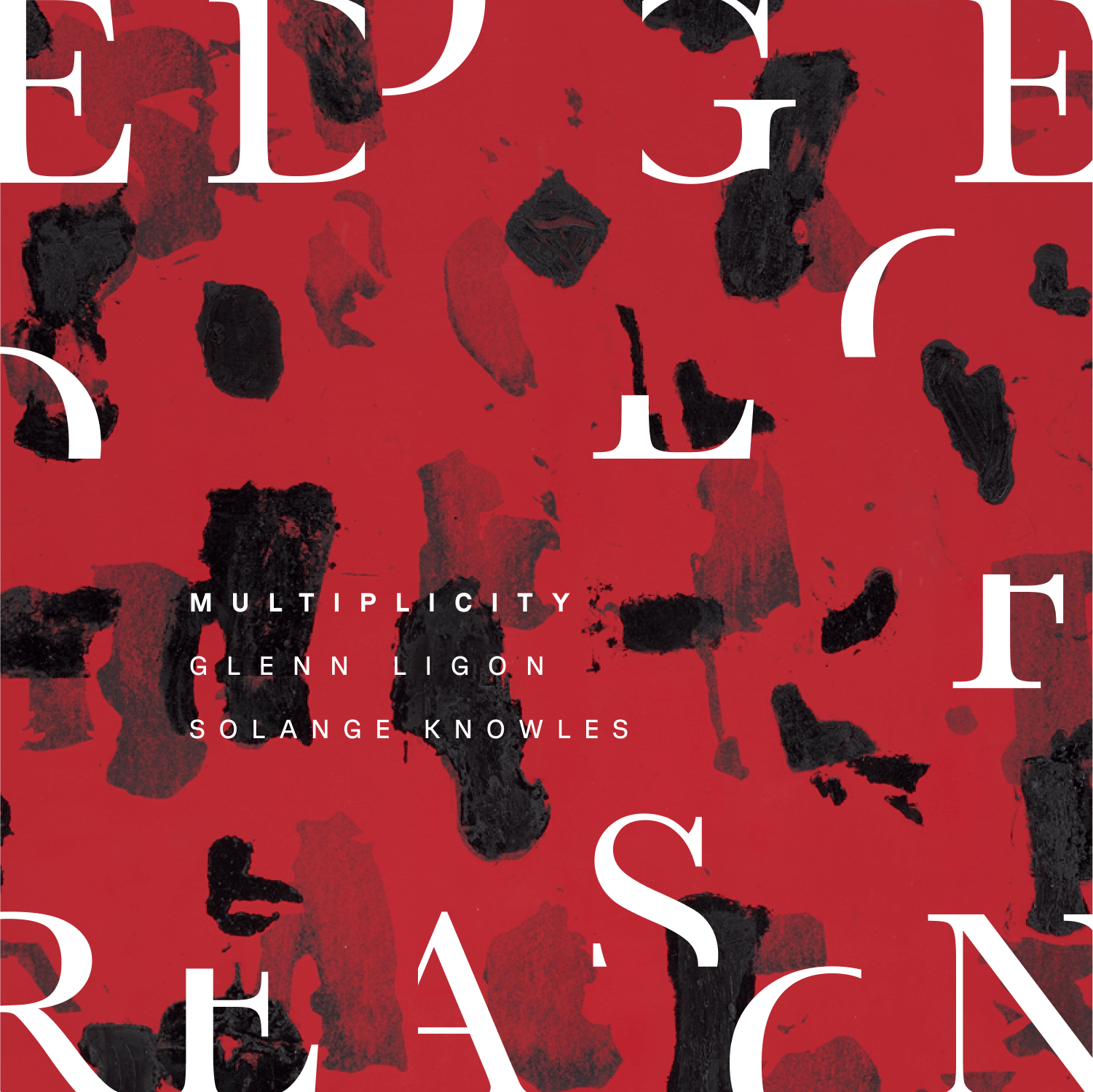

In the second season of our podcast with Hauser & Wirth, we explore the line where left-brain meets right-brain; where logic ends and creativity begins—beyond the edge of reason.

Hosted by Jeff Chang

Episodes

⊖

LATEST EPISODE

Process

Annie Leibovitz

with

Amy Sherald

LISTEN NOW

Annie Leibovitz

with Amy Sherald

PROCESS uncovers how vulnerability and intuition come together in the creative journey, revealing the humanity behind the art.

In this special bonus episode, celebrated artists Annie Leibovitz and Amy Sherald join Ford Foundation President Darren Walker in a candid conversation about the complexities of process. Leibovitz reflects on her journey as one of the most iconic portrait photographers of our time, balancing intimacy and theatricality, while Sherald shares insights into her luminous reimaginings of identity and culture through painting. Together, they explore the intersections of their crafts, their shared reverence for intuition, and the beauty found in the messiness of creating. Moderated by Walker, their discussion offers an inspiring look at how art evolves from life and transforms our understanding of humanity.

Edge of Reason, Season 2 | Process

SECTION ONE | THE THEME

JEFF CHANG: The creative process: an unfolding journey where life becomes art. It’s about more than just the finished work—it’s about the moments of discovery, the unexpected detours, and the vulnerability of shaping raw experience into something that resonates and endures.

Process is where the magic happens: where intuition meets intention, and where the act of creating becomes an / exploration into what it means to be human.

What happens when two artists with unique approaches to their craft come together to reflect on their processes? How do their methods, experiences, and perspectives mirror and contradict and illuminate one another? What can we learn about the process of creation and the power of creativity from the intersections and juxtapositions of their work?

I’m Jeff Chang and this is Edge of Reason…

<< Theme Music >>

…a limited-series podcast produced by Atlantic Re:think—The Atlantic’s creative marketing studio—in partnership with Hauser & Wirth—a home to visionary modern and contemporary artists.

As a special episode this season, we’re excited to share a live conversation between two extraordinary artists whose work captures the essence of life itself.

Annie Leibovitz is one of the most iconic portrait photographers of our time, known for her ability to balance intimacy and theatricality.

Amy Sherald is one of the most iconic portrait painters of our time, celebrated for works that picture the breadth and luminosity of American culture.

Together, in conversation with Ford Foundation President Darren Walker, they unpack the beauty, challenges, and humanity embedded in the act of creation. They talk about painting and photography and how to capture energy. They talk about how they came to some of their most famous works, and also the work they did together. And they talk about the business of being an artist and the messiness and the delight of process.

Here is that discussion.

<< Applause >>

DARREN WALKER: Good afternoon everyone, and welcome. You are in for a treat.

AMY SHERALD: Annie and I are nervous.

DARREN WALKER: So we were just back in the green room.

AMY SHERALD: No, no, no, no- [inaudible].

DARREN WALKER: We were just back in the green room and they were saying, “Why are we here?”

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: We’re wrecks.

DARREN WALKER: “Why are we here?”

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: We’re wrecks.

AMY SHERALD: Artists that don’t know how to do or don’t like to do artist talks, raise your hand.

DARREN WALKER: But you are here, and you are here because we need to hear from Amy Sherald and Annie Leibovitz. We need your voice, we need your perspective, we need your art. Each of you-

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: So you should go to Hauser & Wirth and you should go definitely to the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco.

DARREN WALKER: Each of you-

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: And it’s going to be the Whitney soon, which is great.

AMY SHERALD: Yes.

DARREN WALKER: We’re going to get to the promotions in a moment but-

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Oh no, no, so what I wanted to tell you is I was doing my research and you said you were doing your research, and you were looking at me and I was looking at you, and then my editor, Sharon Delano, sent me an article that David Hockney had written about is Painting Better Than Photography., And it sent me, and it’s tizzy because of course he ended up saying that painting was better than photography. And then I got-

DARREN WALKER: You didn’t like that, you didn’t like that answer.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: But then I kind of looked it up and I realized it was written in 2004. And I said, “This is coming from a painter.” And also in 2004, because so much has happened since then with photography and digital work, and he did mention towards the end of his piece that with the on put of new technical digital work, it was coming closer to painting, and I thought that was interesting. But you [inaudible] worked with photographs too, so I always found that very interesting.

AMY SHERALD: It depends on what kind of painting, right? Because I think photography and painting are similar when you’re using film because it captures the same thing. I was just recently watching One Hundred Years of Solitude and in the series, this guy brought the main character daguerreotype, camera obscura. Did I say that right?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: No, no, I think it’s a couple of things put together.

AMY SHERALD: So it was the beginnings of the camera.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Back in.

AMY SHERALD: Yeah, and his intent, once he saw his first image, was to try to go around and take pictures to try to capture God, to see if we could take a picture of God. Like God is out there, let me see if I can take a picture and this energy will allow itself to be seen. But I think in painting, and when you work with film, let’s say, I don’t know what kind of film, because technically not a photographer guys, so 35 millimeter camera.

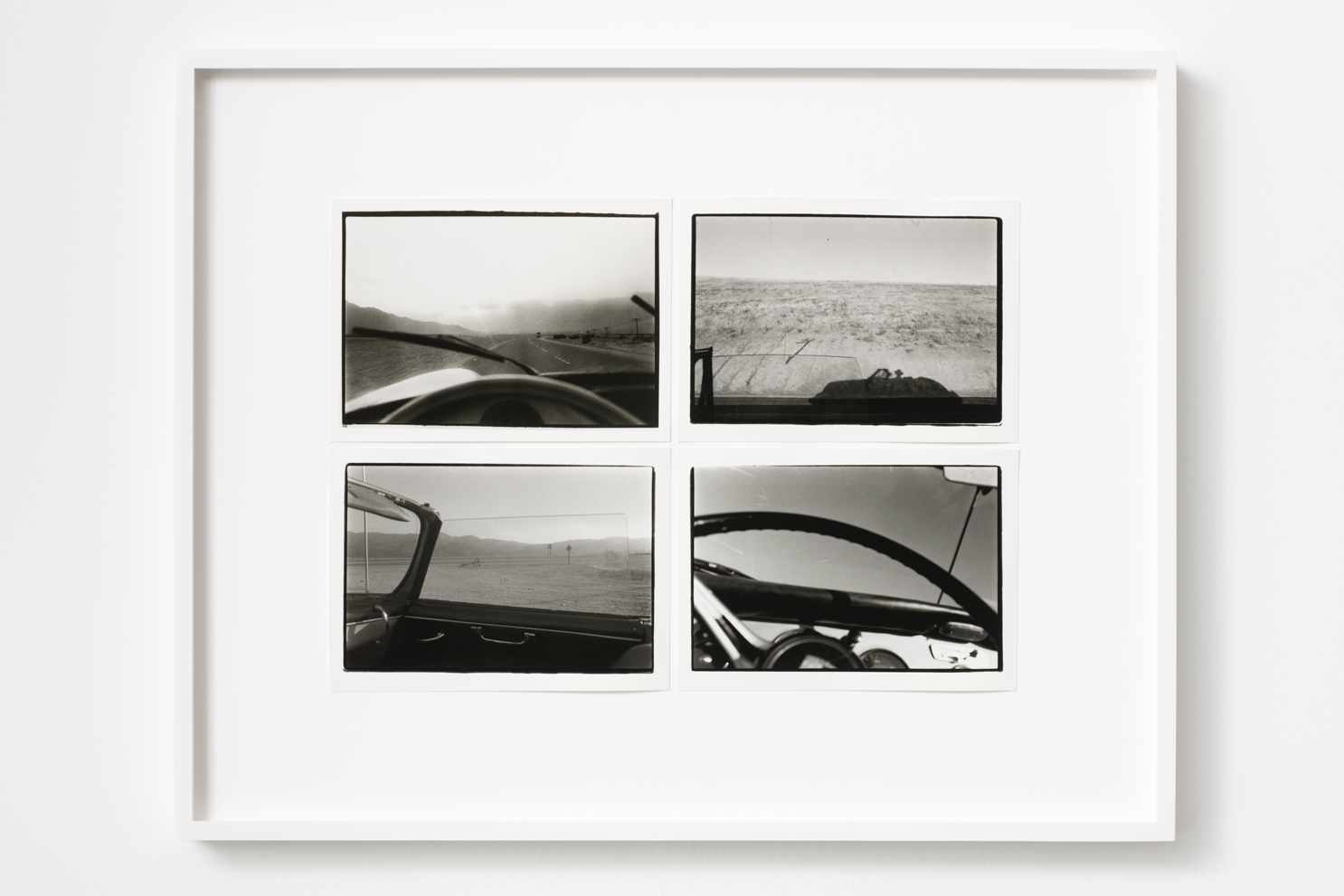

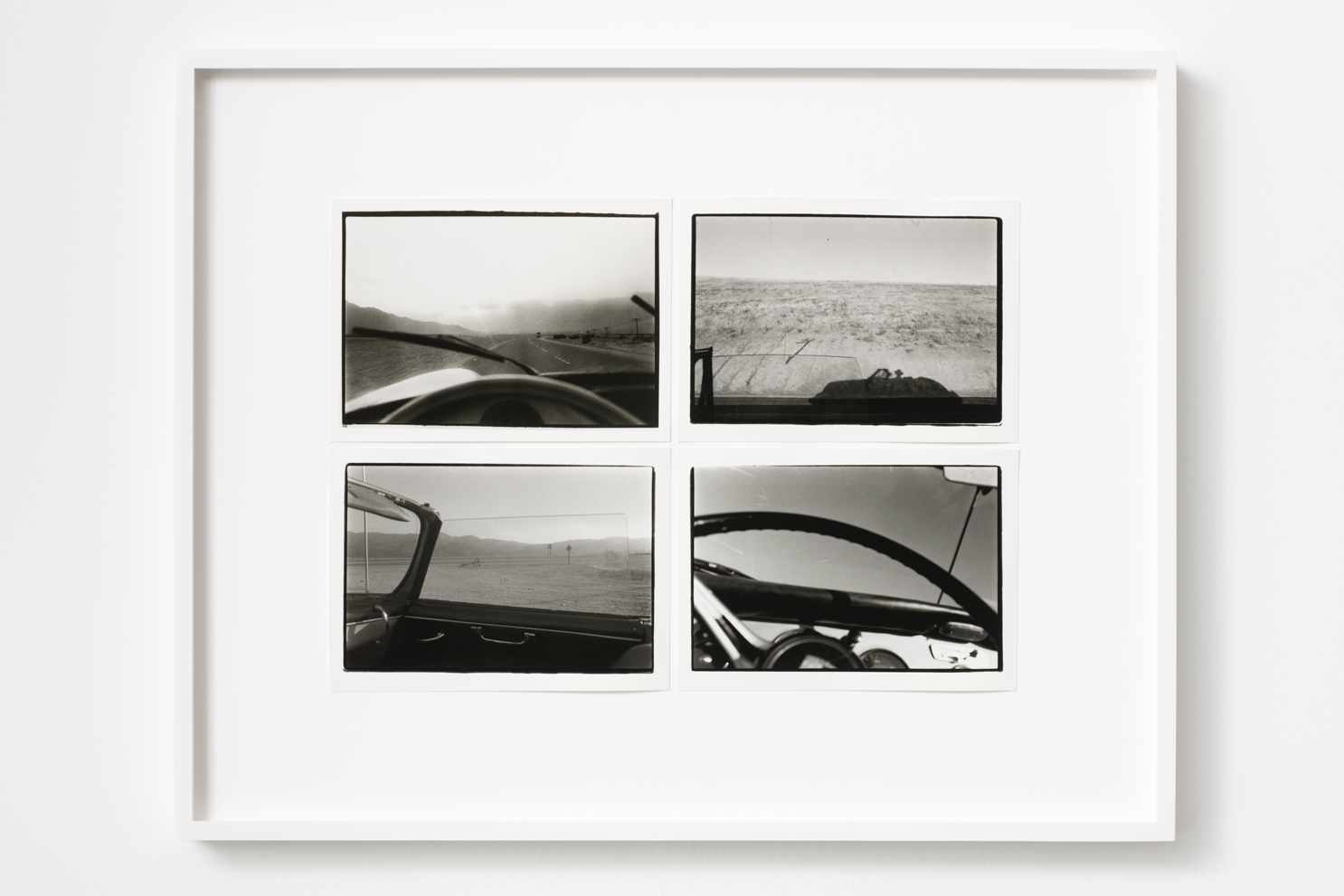

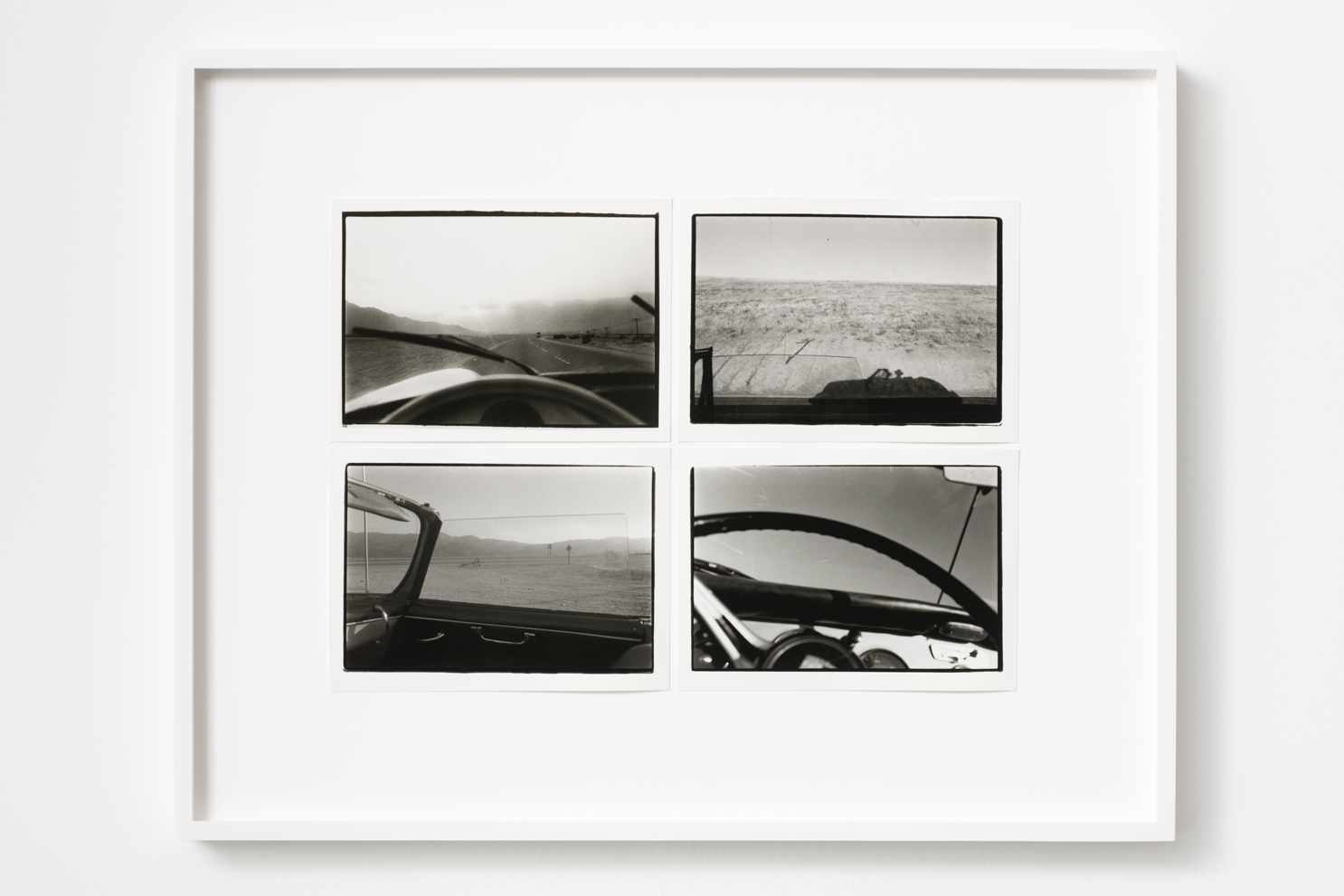

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Now, it almost anything. In fact, Hockney himself, sort of Hockney himself sort of introduced me to the idea of breaking the frame, because having done this a pretty long time, my original work was really based on Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank, 35 millimeter in a frame. Basically Hockney did these photo montages of all these photographs kind of put together, and I said, “Oh my God, that is how the eye actually sees.” And I see what he means about how limiting photography is. But it is different for us in portraiture, I think-

AMY SHERALD: I think so.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I think the way you use photography… Anyway…

AMY SHERALD: We’re going after the same thing, and I think it’s energy. I think in your work you capture the essence of what it is to be human. In my work, I capture the essence of what it is to be human, and it’s the energy. And I always bring up Alice Neal, because she wasn’t a realist painter, but she also captured the essence of what it was through paint.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: See, I was so jealous of you as a painter, and I would cite Alice Neal as well in portraiture, because you can look at Alice Neal as it’s definitely done in pieces. You feel like the portrait is done and she’s looking at different parts of the body, and she’s painting them, and it creates movement. So all I’m really trying to bring up now is the new digital work, I’m actually coming clean now and saying I’m starting to take pieces and work almost like a painter, but not… Anyway, Alice Neal.

AMY SHERALD: In your beginnings, you were a painting major, right?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Not a very good painter.

AMY SHERALD: What was your work like?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: But I didn’t have the patience to, I was too young. I see what it takes for you to paint.

AMY SHERALD: And I desire the instant gratification of the camera.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I’m sorry, what?

AMY SHERALD: I said I desire the instant gratification of the camera.

DARREN WALKER: Do you feel that the camera is a medium that gives you instant gratification? Do you feel that the camera, you get gratification?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Nothing’s instant, it’s bullshit. Nothing is instant, it really is… Just look at-

AMY SHERALD: It’s the grass is greener kind of thing, I feel like the grass is greener, but it’s really not.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Originally, originally it was, originally it was fast, originally it was as a young person, you’re out there just photographing everything and then you’re not really, but now it’s definitely more… Anyway, I do want to say that what I do is really working in popular culture, what’s going on right now, and you are doing something, Amy, you are a genius, you really…

AMY SHERALD: You’re a genius.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: You are a genius.

DARREN WALKER: We have two geniuses that are acknowledging that each is a genius.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I just have to say kudos to this catalog because what happened was, these are my notes, my daughter said, “Mom, don’t take that up on stage, you’ll never find anything.” But to see this done in a way where you turned a page, and it’s so powerful to me to see your work like this, to see how you really are thinking in this catalog, and you’ve started, maybe all along you’ve been making it up. I’m not making it up, but you’re making up a world that is… I’m so, again, envious, I’m dealing with kind of a semi-reality, although there’s no such thing as reality, but-

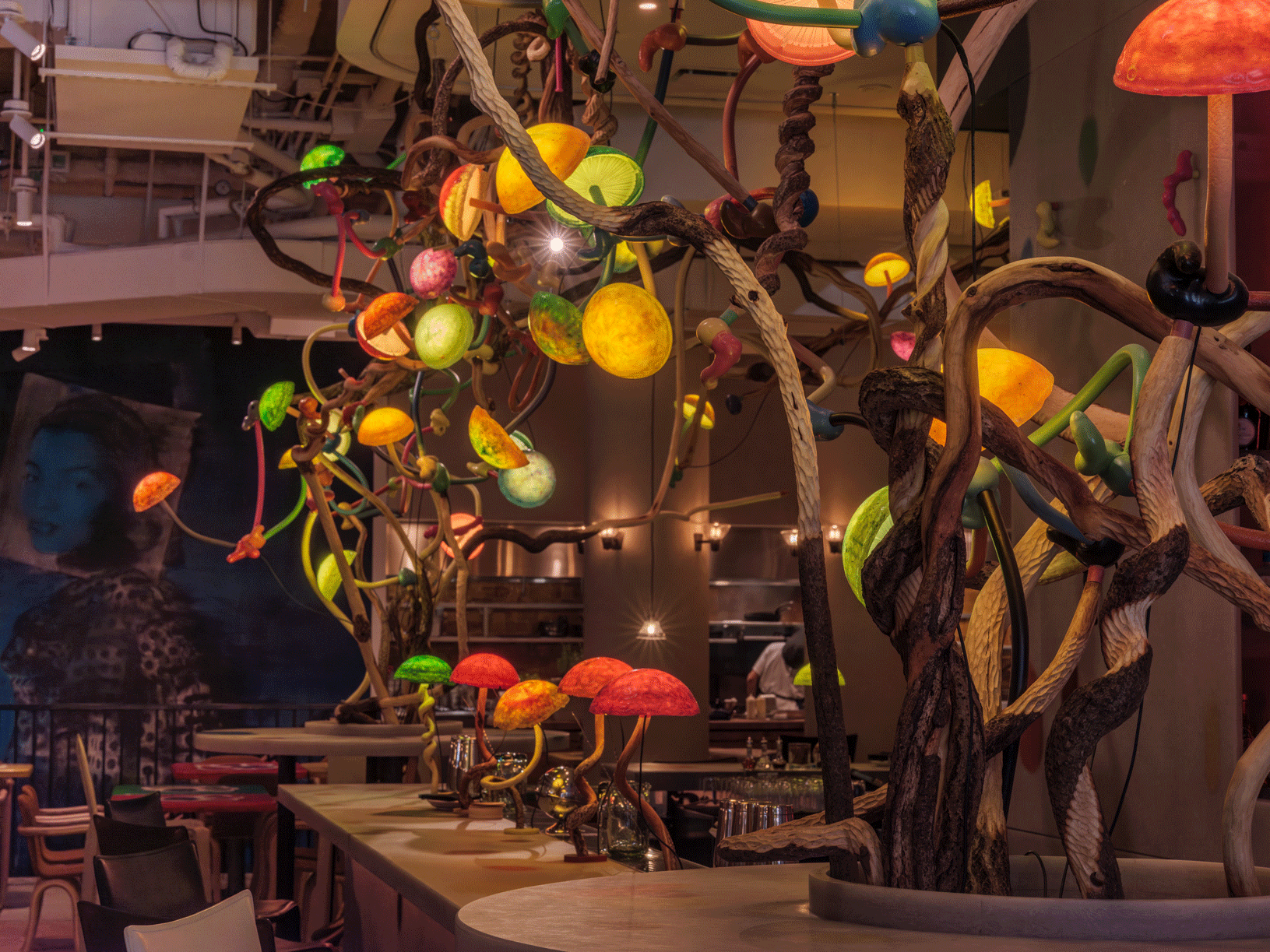

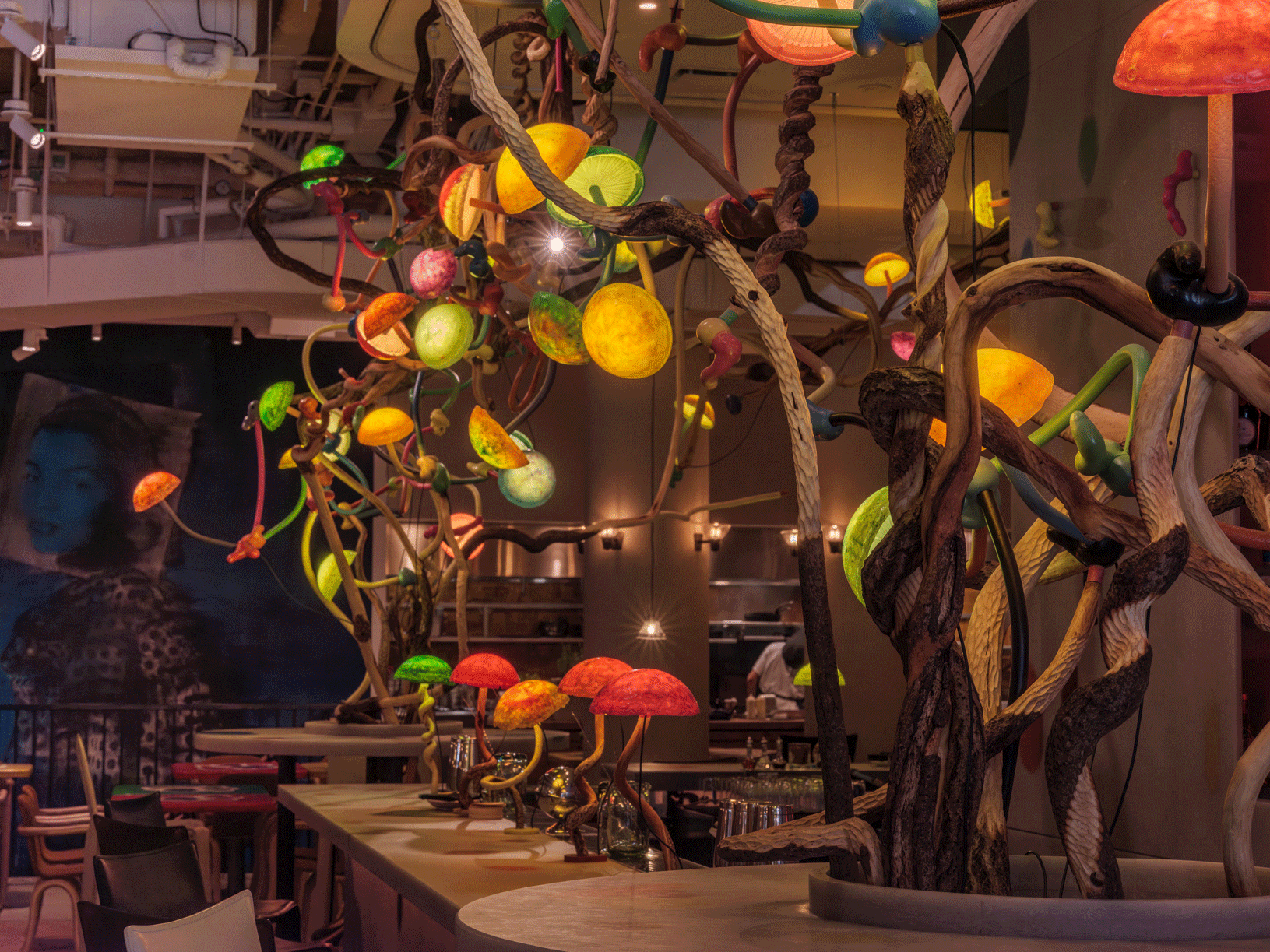

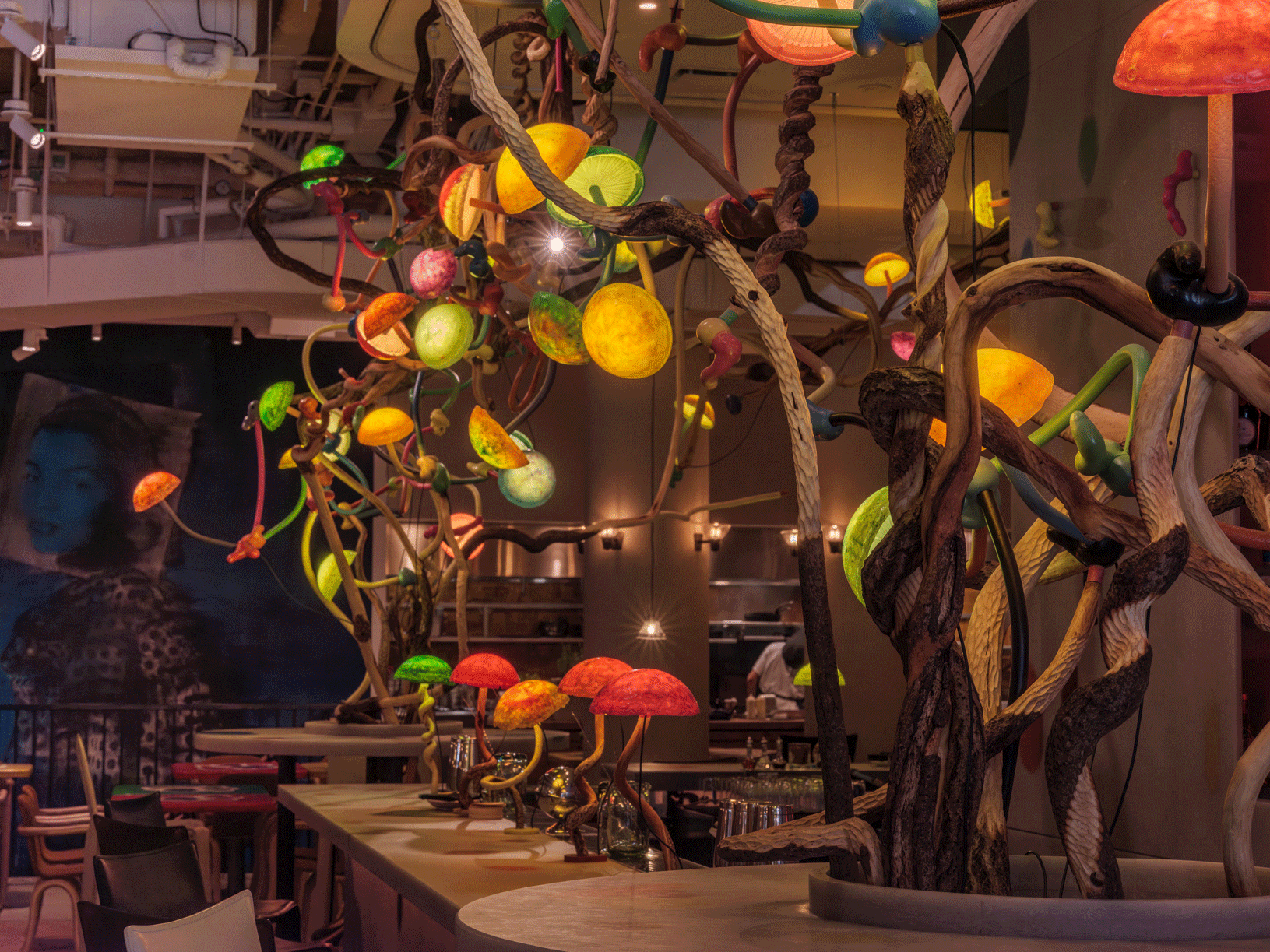

AMY SHERALD: I see world-making, when I look at your catalogs though. When I went through Wonderland, that was world-making, and because I also went through a phase where I was really into Alice in Wonderland, and I just love to see the theatrics, and the tonality, and the narrative, and how you composed these images, it was beautiful, it was wonderful.

DARREN WALKER: But one of the things you do, Amy, I think, is you have a particular insight, and perspective, and representation of Blackness, and of a humanity, and of a dignity that you seem to be compelled to want to paint. One of your favorite paintings, there are so many beautiful, amazing AMY SHERALD paintings, is the painting, “Welfare Queen.” I love that painting. Talk about Welfare Queen.

AMY SHERALD: Well, speaking of film, it’s the only painting that I ever thought about making into a short film. When I say short, it could be like 30 seconds. But I had a studio in Baltimore, Maryland, and I would walk to my studio from where I lived, which was this neighborhood called Bolton Hill, and I would have to walk up a street called Utah Place. And on this street, it was like there was a market called Lexington Market, there was a methadone clinic, it was just complete and total chaos. And I came up with the idea because I was thinking about a painting, and there was this girl that was standing on the corner, and I was standing there, I used to listen to, on repeat, I would always listen to the March of the Penguins soundtrack for some reason.

So there’s all this chaos around me, there’s people yelling, there’s the guy that just got out of prison whose name was Swole, who’s selling water. There’s Fruit of Islam, there’s a woman who was miming to gospel music on the corner, and then there was just this one girl that was standing there. And in my mind, I imagine that all these people that were walking towards, her past her, that they were taking something off of her and putting something on her. And for some reason, Chicken Soup of the Soul is coming up, but maybe I was reading that book at the time, I’m not sure, but in the painting itself is a friend of mine named April, who was born in Baltimore, Maryland in a neighborhood called Cherry Hill. And she was the first in her family to go to college, went to Harvard, she went on to Columbia. And for me, she represented that kind of evolution, that transformation, and so she is Welfare Queen. And so after they transform her from this young girl to this princess, then she’s walking around on stilts, I guess, so she’s bigger than life and she’s handing out something, I’m not sure yet. But this is why I’ve never made this movie because when I talk about it, I’m like, “Yeah, no, it’s not going to be good.”

DARREN WALKER: I think there’s great potential. Annie, you have in some ways created the soundtrack of American Life through photography, and you have photographed just about every celebrity. And not only have you photographed them, you have done the iconic photograph. So I think about Demi Moore, a pregnant Demi Moore on the cover of Vanity Fair. Was that your idea or did Demi say, “Let me get naked and take this picture”?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I had photographed Demi and Bruce Willis together on occasion, and Vanity Fair was doing a cover on Demi Moore. And they said, “The only problem is Demi’s pregnant, so you’re going to have to work around that.” Because no…

DARREN WALKER: You’re going to have to work around her pregnancy?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: In those days, you didn’t photograph someone looking pregnant. So I went out to LA armed to basically photograph Demi’s face, do a head portrait, which I’m not very good at by the way, and interestingly enough, I had done some work with Demi and Bruce when she was pregnant with her first child and I did some photographs of her nude with Bruce, pregnant, and on another occasion. And so I said, “Listen, since you’re here, let’s go ahead and do some pictures of you nude now, so you have the second child.” And photographed, so you can see the baby. And so we took these pictures, and as I was taking them, I said, “You know, I wonder if this could be a cover, if we could run this.” I brought the material back to New York, Tina Brown was the editor, and I was with Susan Sontag at the time, and Susan saw it and she said, “You have to do this. I’m calling Tina Brown right now, you have to run this. This is too important, you have to do this.”

And at the time, we actually reached out to Demi and said, “How do you feel? Are you comfortable?” We didn’t really know what its ramifications were and how important it would be in the scheme of things. And Demi and I talked about, well, what does it mean? We had to try to figure out how to talk about it. And of course, it turned out to be so important. Doctors put it in their offices.

DARREN WALKER: Well, it’s a cultural. You transformed what, for centuries, had been this difficult cultural reality of pregnancy and the inconvenience of the way a woman looks while she’s very pregnant especially, and you transformed something into a cultural asset. All sorts of women now get naked when they’re eight months pregnant, it’s transformed the way as a cultural phenomenon [inaudible].

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I think of how Rihanna brought it full on, and I admire Rihanna so much for she’s walking around, and it’s so beautiful, it is beautiful now. It’s very, very beautiful.

DARREN WALKER: That’s the power of art, right? It is the power of art. And Amy, when you think about the moment you learned that Michelle Obama had chosen you.

AMY SHERALD: Come on church.

DARREN WALKER: It’s not as if you were unknown, you had gallery shows, I’d seen your work at Monique.

AMY SHERALD: I was known in the art world.

DARREN WALKER: In the art world, you were absolutely known. And of course-

AMY SHERALD: But baby known.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I just want to add one quick thing I have to say about Michelle Obama. Having worked with her the year she was in the White House, what you gave her in that was you gave her back herself because she had lost herself in the White House, and you gave her back her dignity and herself and who she was, and it’s such a powerful, powerful portrait.

AMY SHERALD: Thank you. That means a lot, oh my God.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Oh my God. I felt so bad for Mrs. Obama, for Michelle, towards the end especially, she just hated it, just hated it.

AMY SHERALD: It was rough. It was rough-

DARREN WALKER: And so where were you? Were you driving on I-10? What were you doing when Thelma Golden called you and said, “Go to the White House”?

AMY SHERALD: I wish Thelma had called me. I met Thelma for the first time in the White House, and I’m sitting there like, “Should I be more excited to meet Thelma or Barack?” Because I’m kind of excited to meet Thelma. But Dorothy Moss called me, I was in my studio, I was in a residency, like a three-year kind of live/work space residency program in Baltimore. And yeah, I was working, I was painting, and she called and she’s like, “You should sit down.” And I’m like, “I don’t want sit down, just tell me what it is.” And she said, “She chose you to paint her portrait.” And I was like [inaudible], it was just like, ugh. And I sat down with my dog, August Wilson, who was also a Virgo like his mom, and I was like, “Your mom’s going to be famous. You’ll never have to eat cheap dog food again.”

But I also had a knowing, I had a knowing. I’ve been through a lot in my life, and I always say I didn’t survive everything I went through not to make it. I didn’t know whether I was going to be chosen or not, but I had a very strong feeling about painting her, and even in the interview process, I didn’t realize that I was there to talk to her and Barack, and Barack was there, because in my mind, the opportunity only came with me putting her image into the world and connecting with her. And I think I remember Barack had asked a question too and she was like, “No.” He was like, “How would you paint me?” And I was like, “I don’t know, I actually haven’t thought about it.” Because in my mind, I was thinking about Michelle because I felt-

DARREN WALKER: I’m not interested in painting you, I want to paint her.

AMY SHERALD: I would have, but Michelle is Michelle, and even Barack knows she’s more popular than he is.

DARREN WALKER: I told you guys you were in for a treat. Okay, Annie did you know that you were going to be Annie Leibovitz? Did you know that you were destined to be amazing and that you had this talent that you knew as a kid?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: We love our work, we work, we just love what we do, and that propelled me through all of these years. And even to this day, I love what I do. I am on a mission for the body of work. Having done this so many years and have such a big archive, to look at all these years, it even overwhelms me to understand. So I feel very responsible to the body of work, and sense of history, and culture and that I will continue to do that. But thank you, thank you.

DARREN WALKER: You’ve talked about history and your loving history, and you understand that photography has a particular role. When I think about Frederick Douglass and those, those photographs,

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: That was a very important portrait of him.

DARREN WALKER: And he was the most photographed man.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Yeah, he was for sure.

DARREN WALKER: In the 19th century, and it was really important that he was, but you see yourself as documenting history, not a photographer, but you truly see yourself having a responsibility to do that.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: And I like to try to stay current.

AMY SHERALD: I didn’t realize that you were a wartime photographer until I was going… I don’t know why, I’ve looked at so much over the past two weeks about you, but I was reading about Sarajevo, and I didn’t realize that you were there photographing in the midst of everything that was happening.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Well, Susan Sontag went, and to her chagrin, I trailed along. Well, I think it’s important to be in places. It’s interesting because with everything that’s going on now, I do think some of the greatest photography that’s so intact right now is our photojournalism. I think it’s really very powerful. I think photography, in answer to Hockney, we’ve never had better photojournalism as right now, and every single day in the newspaper or online, we see things, it’s so powerful.

AMY SHERALD: The way the fires are being documented right now also, just shout out to the photographers in Los Angeles.

DARREN WALKER: The way the fire in LA is being documented, they’re great.

AMY SHERALD: Those images are so powerful.

DARREN WALKER: It’s amazing when you think about the photography right now, and you talk about instantaneous, but what is being transmitted, as you say, Amy, during the last week around the fires gave you a sense of urgency, and as only photography can do. You felt like some of the photographs, you literally could feel heat emanating from the pictures, the photography was that powerful, that profound.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Definitely the still is alive and well, I have to reach out to David Hockney actually soon and have a talk with him.

AMY SHERALD: Let’s all have coffee because I would like to meet him.

DARREN WALKER: I have a feeling he would still believe that painting was indeed.

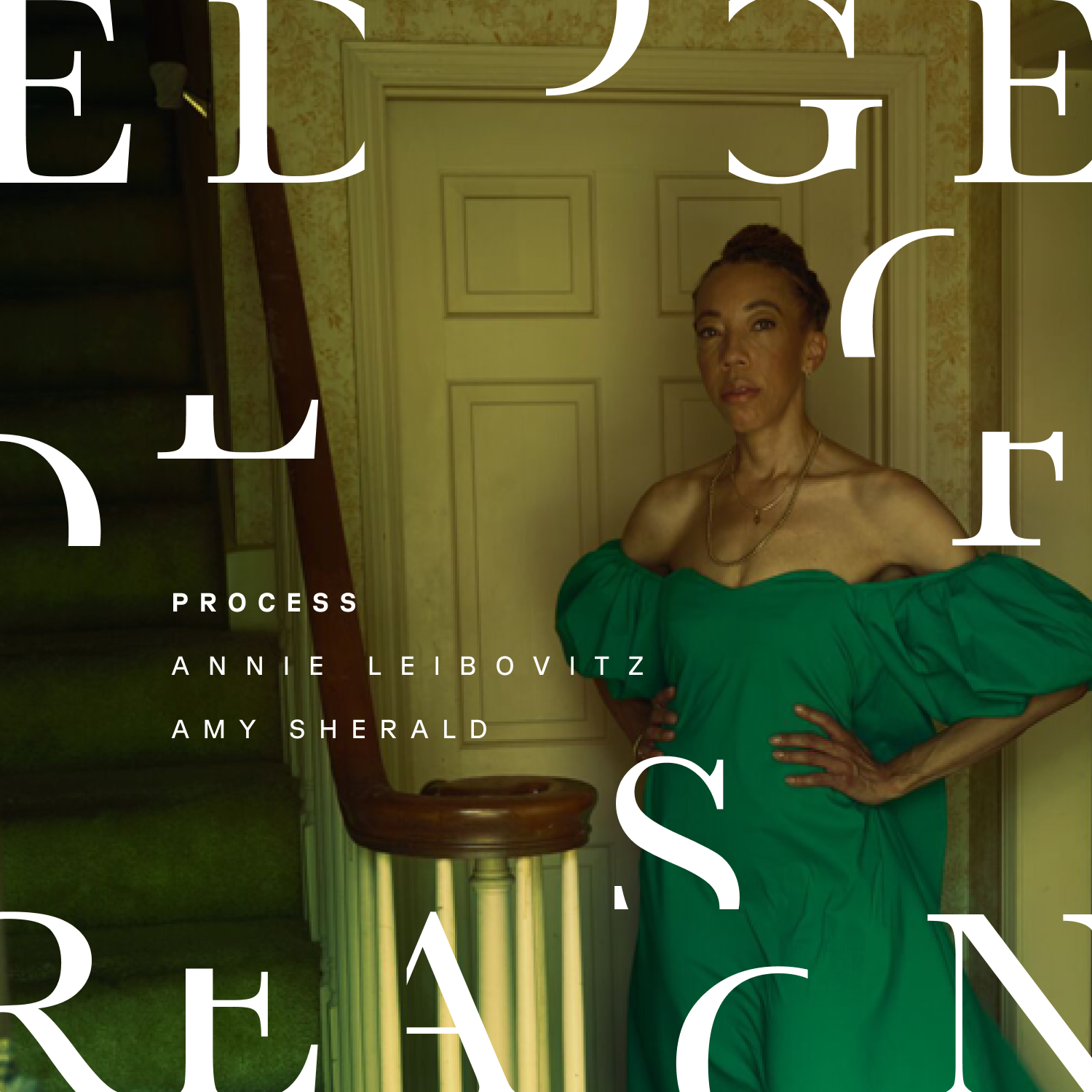

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: But Amy actually, we have unfinished business because I was thinking about the session that we had, the first one we had, and I don’t even remember those pictures because I was so obsessed with what you told me, you told me about how your mother had kept your childhood home, your room exactly as it is.

AMY SHERALD: Exactly the way that it was when I left.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Growing up, and you weren’t allowed to put any imagery on-

AMY SHERALD: No posters on my wall in my bedroom. The bedspread matched, the bed ruffles matched the floor, matched the paint on the walls, everything was pristine. And it’s funny. So what’s interesting, and this is how when I say you walk into a space and you don’t have a plan and let the plan evolve. When Annie came to Columbus, Georgia to photograph me in that house, which my parents built in 1973, we had not been in that house for three years. And so this was 2023, Covid had come upon us. My mom, my sister and I, we all hunkered down in Atlanta, Georgia. So we hadn’t been back there, so I unlocked the door and I looked back at you and I was like, “I don’t know what we’re walking into.” And what we walked into was a roof that had collapsed, there was black mold everywhere, you literally couldn’t breathe for more than two or three minutes without having to go outside. And I was like, “I don’t think she’s going to be able to do this.”

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I said, “I think I came too late for this house, for this moment.”

AMY SHERALD: And it’s incredible, you made it work.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: No, what I love about you is you brought this green dress, and I was like, “Okay.”

AMY SHERALD: What do you wear when Annie Leibovitz photographs you?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: You’re very much in control, whatever the situation is, and I have to go with it, it’s all right with me. It’s just like I was trying to figure out how to have a full length green dress in the bedroom. And so we went up the stairs and I couldn’t even get far enough back to photograph the whole length of the dress. I actually did not know what I was doing, and then we ended up going back downstairs, and it really was like the front door opened and the natural light came in, and you saw the darkness of the house behind you, and in the stairwell there, that’s where we ended up taking the photograph. And it’s not attractive of you, and you are a very attractive person, obviously.

AMY SHERALD: Thank you.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: But I let it go, and I’m at the point where everyone should look as good as they want to look. And I let it go, and for that reason, you had your hair pulled back very tight.

AMY SHERALD: I had a lot going on, and I was like, “I’m a black woman, it takes time to do my hair. And if I take these braids out.” It was just a whole thing, so I was like, “What am I going to wear for Annie to photograph me?” This is a big deal, I don’t have a stylist, I was like, I didn’t know what to do, so I was almost panicked and trying to figure out what to wear.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I would say that picture is very accurate for the moment. It’s definitely a helter-skelter picture, and there’s something-

DARREN WALKER: Its a beautiful picture I found, it’s a gorgeous picture. [inaudible]. First of all, I think it’s a powerful picture. It’s not just in any green dress, it’s like a Balenciaga gown. You look fabulous, as a gay man, I love that dress, I love that coat.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Daren, you are absolutely right.

DARREN WALKER: She looked fabulous.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Listen, I printed it. No, what I’m trying to say is there’s another step to do with Amy. It is my job to figure out which story we’re going to tell. That is what I do like about portraiture, is that it’s not journalism, and I have the opportunity in portraiture as well to have that point of view, and that is why I can be conceptual and that interests me a great deal. So that’s why I’m not finished, and that is actually, if there’s a secret to my work, I am not afraid to go back.

DARREN WALKER: So you’re going to go back and have another round with Amy Sherald?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Yeah, and we’re going to have a collaboration next time.

DARREN WALKER: And where will you go this time?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: We haven’t talked about it.

AMY SHERALD: Annie will know. I don’t know, I’m just going to do whatever she wants me to do.

DARREN WALKER: Can we be witness to this or is it just between the two of you?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Hey, we’re very introverted people.

DARREN WALKER: I love that were saying backstage, “We’re so introverted, we won’t talk. It’ll be really hard for us to talk, you’ll see.” Been really hard to get you two going.

AMY SHERALD: It’s like a cold plunge. You just got to jump right in and you’re like, “Oh my God… “ And then you’re like, do you know what you just said? No, but we started talking.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: It’s a miracle.

DARREN WALKER: It is not a miracle. So let’s talk about though, how the body of work you’re pursuing now, is it evolving, is it changing? You, Amy, and I know many of us would love to hear about the upcoming show at the Whitney and all the amazing things that we saw out in San Francisco and hoping that it’s all coming to New York.

AMY SHERALD: Most of it is coming, and then there’ll be some add-ons as well. It’s honestly so hard to talk about that show because my brain is already in the next dimension, and I’m just trying to figure out how to evolve. And I think I’m living this big question now and trying to match my practice with the pace of the art world and what my needs are as a creative person.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: This is the last time she’s doing this is what I’m saying.

AMY SHERALD: And I had a conversation with myself a couple of weeks ago and I was like, I haven’t had a lot of time to play in my studio, I just don’t have time. Somebody asked me today, we were having luncheon, and Chanel asked me if I draw, and I’m like, “I kind of don’t have time to draw.” I have ideas and I have to make them. And there’s the art market, but then there’s the artist, and I’m thinking maybe I should just make some stuff and have a show just about stuff that I made, because it’s part of the process. Everything doesn’t have to be this perfect presentation, it can be like, these are some different thoughts and different ideas that I was working on. And maybe you won’t see this stuff again, this is a one-off because it’s stuff that I wanted to paint but couldn’t quite articulate how it fits into this bigger picture. And then through that process, I’ll go back and find myself again and move on, but I’m really considering that, just having a show where it’s just like, these are some things that I’m thinking about. I said I was going to name and a few of my favorite things, but-

DARREN WALKER: I think we all would love that, Amy, and one of the reasons, many reasons, you’re so admired is because it takes a long time to produce an Amy Sherald painting. You don’t have a lot of people in the studio helping and it takes a long time, and therefore, the commercial demands, because everyone wants an Amy Sherald painting, as you know.

AMY SHERALD: Thank goodness.

DARREN WALKER: And my wonderful Kaywin Feldman is out in the audience, the Director of the National Gallery of Art, where I am president, and we have waited to get in line to get an Amy Sherald, and I think we may finally have one.

AMY SHERALD: Yes.

DARREN WALKER: It has been an ordeal, and we’re the National Gallery of Art okay, to get an Amy Sherald painting because everyone… But I can imagine the demands on you when you know the National Gallery of Art is waiting for a painting of mine.

AMY SHERALD: Yeah, I know, I can’t sleep at night. It’s like…

DARREN WALKER: And so I think one of the things that is wonderful to hear, you just sort of freestyling. “I may just do something different. That’s just some stuff I want to do.”

AMY SHERALD: Just want to get it out, and I should be able to get it out without being, I don’t know, I don’t know whether it be criticism or whatever, but I think the art market expects something. Once Coke made Coke, they couldn’t change the formula, it’s like it has to be Coke. And so there is a level of branding I think that happens with art making, and that’s fine, but how do you explore within that realm? How do you evolve and make the next album, essentially?

DARREN WALKER: Right. Well, and you are articulating what every great artist in our capitalist system is confronted with. People want that, they want that Michelle Obama-like portrait. And you may say at some point, “I’m tired of doing that and I think I want to do something else.” And I love that you’re willing to assert your agency over your own creativity.

AMY SHERALD: Yeah. I’m only a slave to myself.

DARREN WALKER: And for you, Annie, as an artist who, so many people over the years have said, wanted to commission an Annie Leibovitz photograph of themselves, because we know that with portraiture, having the most important documenter of whatever, whether it’s portrait or photography, painting or photography, they want to have, well get Annie Leibovitz. Are there people you say, “I just don’t want to take your picture.”

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: It’s actually very hard to do something for someone because there’s an expectation of what they imagine themselves to be, and sometimes you’re not in the same place. It was very hard for me to do portraitures of friends and people that I knew because I knew how they imagine they looked, and it wasn’t necessarily how I saw them.

DARREN WALKER: So with photography, with doing the kinds of portraits you do, it really is about how you see them less than you projecting?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: No, it’s more like how they don’t see themselves.

DARREN WALKER: Because people, particularly the kinds of people who could afford an Annie Leibovitz photograph, think pretty highly of themselves.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: No, no, I don’t think it’s like that. I was just saying it’s just more complicated.

AMY SHERALD: You oftentimes just want to be like, “No, you learn how to be a painter and you paint your own portrait.” So they need to learn how to be a photographer, and then they can take their own, because it’s like, I’m not here to create your vision, you’re here to let me create a vision of you.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: You brought up at the luncheon, the picture of Ella Fitzgerald and-

DARREN WALKER: The iconic Ella Fitzgerald.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: No, no, but it is not. When I drove up to her house, she was later in age, she didn’t live that much longer, and she was in her window on the second story looking out, and she was very closed off from people. And the picture of her should have been in that window looking out. Instead, I did this thing where we did go through her closet, so it was a lot of fun, there were some great clothes in there. And she did have that car in her garage in the back, but we kind of fabricated that, and it wasn’t what I really saw.

DARREN WALKER: But isn’t-

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: So now.I know. And I think back in that, when you’re talking about that picture, I’m thinking, there’s another picture of her.

DARREN WALKER: But isn’t portraiture also about fantasy?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Well, of course. Well, who are you talking to? No, of course. No, it can be a lot of things. Yeah, it’s big, which makes it not real.

DARREN WALKER: No, we started by saying it is real.

AMY SHERALD: Is portraiture?

DARREN WALKER: Are pictures real?

AMY SHERALD: No.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Okay. Thank you.

DARREN WALKER: Then, but they-

AMY SHERALD: Because everybody turns something on unless it’s like [inaudible].

DARREN WALKER: They may not be real, but they tell us something, they serve a profound purpose, do they not?

AMY SHERALD: They are and can be instructive, yes.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I have to think about that a little bit. I think when you see, because there something very interesting about the collective grouping of photographs from a period of time, they start to reveal something more than just individual pictures actually. I don’t know, there’s something.

AMY SHERALD: Yeah, I feel that way when I walked through my show at SF MoMA, just to see all of my little warriors, I call them, all standing together.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Oh, that’s beautiful.

AMY SHERALD: I always say this, work can be employed in many different ways. On one hand we can say portraits aren’t real, on the other hand, they’re very real and representation matters. So I think it’s expansive, like you said. Because for me, I oftentimes feel like as quickly or slowly, because I’m a painter, as I create an image, I’m battling a visual zeitgeist of the opposite of what I’m doing, and it’s like then I become a machine putting out these images to fight the machine that’s trying to tear them down. So there’s a part of me that wants to… I get out of breath even talking about it, because what it feels like making the work, it feels like there’s so much art history to make up, especially when I think about art history, and I think about, I say this in talks all the time, but I’m like, art history is very long. We’re talking about cavemen, and Black artists who weren’t given a show, a real, real show until the 1940s. And so it’s just like this idea of playing catch-up to art history when it’s so long, so I carry that weight with me, but then I also just want to be free.

I was raised in a church, and so this is the language that I’m going to use, I’m not religious now, but that keeps me in the flesh and I’m trying to live in the spirit, and so where do I find that balance where I can continue to evolve as a person, as a woman, as a Black person, as an American? How can I keep that balance of not getting sucked into the flesh of life and letting my spirit roam and be free, and be creative, and make beautiful things that matter?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I really feel like whatever you’re going to do, you could go either way and it’s going to be okay either way. I am just looking at this line, that through imagination, we can invent ourselves and generate the world we want to live in. That’s you.

AMY SHERALD: That’s me.

DARREN WALKER: And both of you using your craft, have really also been at the forefront of social commentary. I mean, Amy, your portrait of Breonna Taylor, I mean that portrait was a transformational painting in a moment of racial history in this country. Why did you feel compelled to stop everything and paint Breonna Taylor?

AMY SHERALD: I’m still amazed that our lives even intersected. It’s just incredible that I found myself in that moment. It felt like the right thing to do. Again, there’s that responsibility to use this talent that I have, this craft that I have, to assist in creating visual culture around a moment like that, what was happening. And I was scared to do it. When Ta-Nehisi first asked me, I was like, “Oh, no.” But I felt called to do it at the same time. It just felt like the right thing to do, and I felt like the right person to do it.

DARREN WALKER: And for you, Annie, as you think about the moment that we’re living through and the role that you can play as a photographer, an artist, what do you want your contribution to be?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I’ve just looked back to a lot of what I’ve been doing lately, I’ve been photographing a lot of women artists, and I didn’t know I had as many as I had. But it’s kind of powerful to look at at us working in the art world, so it’s kind of amazing, yeah.

DARREN WALKER: I’m eager to hear from each of you what gives you delight, joy, wonder, awe?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Process.

AMY SHERALD: Yeah. I think it’s process too, I think it’s not-

DARREN WALKER: Explain that for those of us who are not art people?

AMY SHERALD: It’s not the painting, so process is everything, process is-

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Were you walking down the street when you saw your friend? That story was so beautiful, that was as beautiful as the painting.

AMY SHERALD: That’s process, process was going to the studio every day and being aware of my surroundings and things find you and you realize that this is supposed to make it into a painting. I think that’s the most pleasurable part of my process, it’s like being able to sit down and watch movies, looking at all of your catalogs, and preparation for this conversation became part of my process. I found so much inspiration in seeing image after image after image of what you have been able to capture. Reading is a process, looking at poetry is a process, talking to friends, just having conversations, everything. Life, it’s just life, because life makes art. You can’t make art without living a life.

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: I just want to say am inspired by your work and your simplicity is so powerful to me, and it reminds me that, I know it’s not as simple as it looks, but you make it feel like that and it doesn’t have to… Anyway, I’m inspired by your work, thank you.

AMY SHERALD: Thank you, Annie.

DARREN WALKER: Final question as we wrap. As we wrap, I want, I’d like to be hopeful right now. Amy, Annie.

DARREN WALKER: Can you help me be hopeful in this moment? Because one of the reasons I will tell you I am hopeful is because of artists. Because in moments when I am bereft, or depressed, or dejected, particularly about any social issue, I think about artists and I think about artists whose shoulders we stand on who did not have the privilege that we have, did not have the abundance that we have, did not complain when they couldn’t get a table at the right time at the hottest restaurant in town, the things that matter to us. They never had that and yet they persisted to create beautiful work, demanding, remarkable, courageous poetry and literature. Are you hopeful? Can you find reasons for hope now?

AMY SHERALD: Yeah, to be honest, and I guess I’m cheating a little bit because my natural affect or default is hope, it just is. So, I have friends who I haven’t spoken to since Trump was elected because they just couldn’t handle life after that, and I was like, “This man about to ruin my life.” You know what I’m saying?

I’m about to paint my off, I’m going to paint my off and get myself ready to fight the fight for whoever. There’s a lot of vulnerable communities out there that are going to be affected, and we need to figure out how to help them.

<< Light Scoring >>

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: She said it all. That’s great.

AMY SHERALD: Life is short.

DARREN WALKER: Join me in thanking Annie Leibovitz and Amy Sherald.

<< Applause fades >>

JEFF CHANG: You’ve been listening to a special episode of Edge of Reason.

We’d like to offer a special thanks to the teams at Hauser & Wirth, Cooper Union, and The Ford Foundation for their involvement in the live event, and for making this episode possible.

If you enjoyed what you’ve just heard, Like and Review on Apple Podcast, and help spread the word about our series to other listeners like you.

And stay tuned for our third season of Edge of Reason coming later this year!

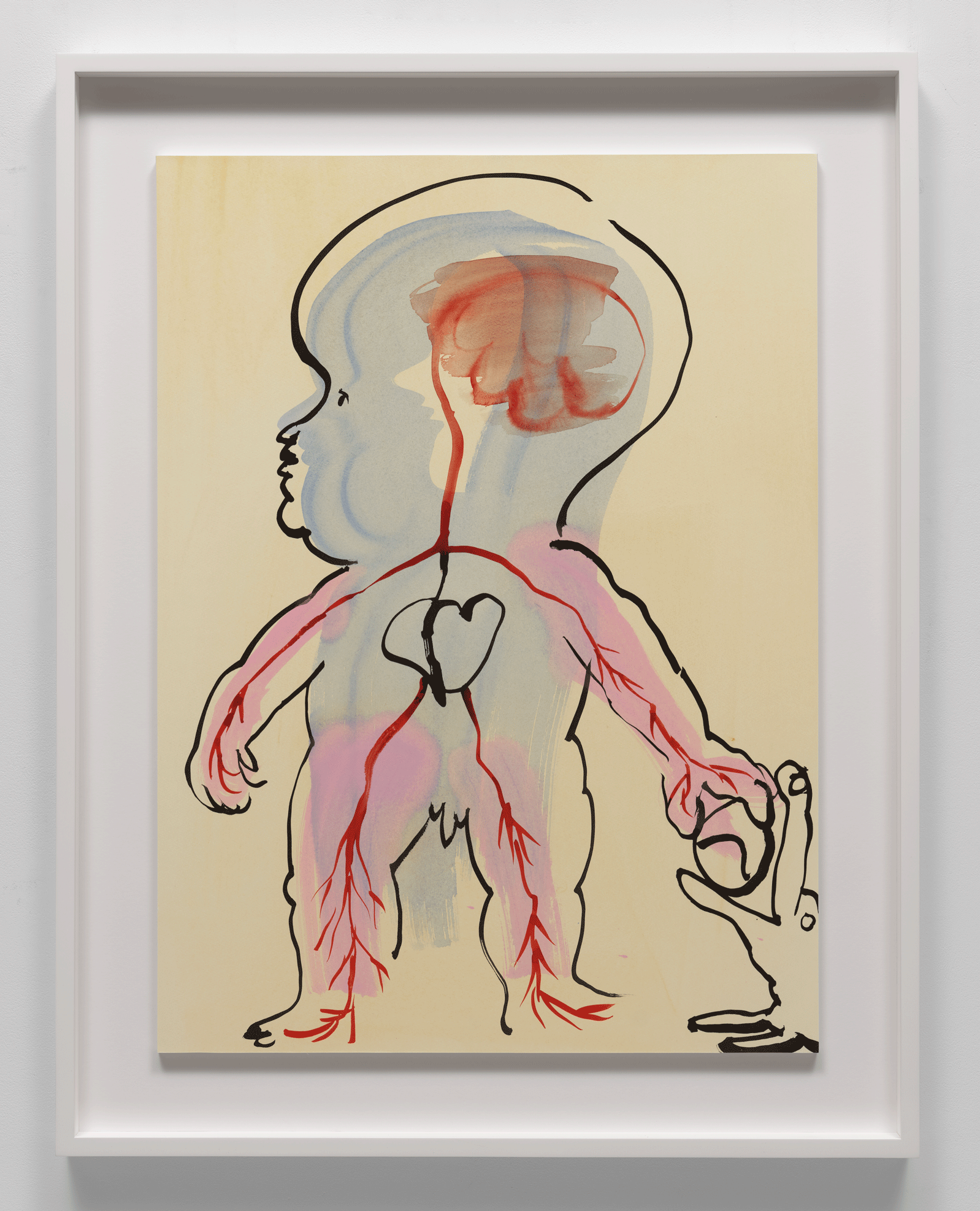

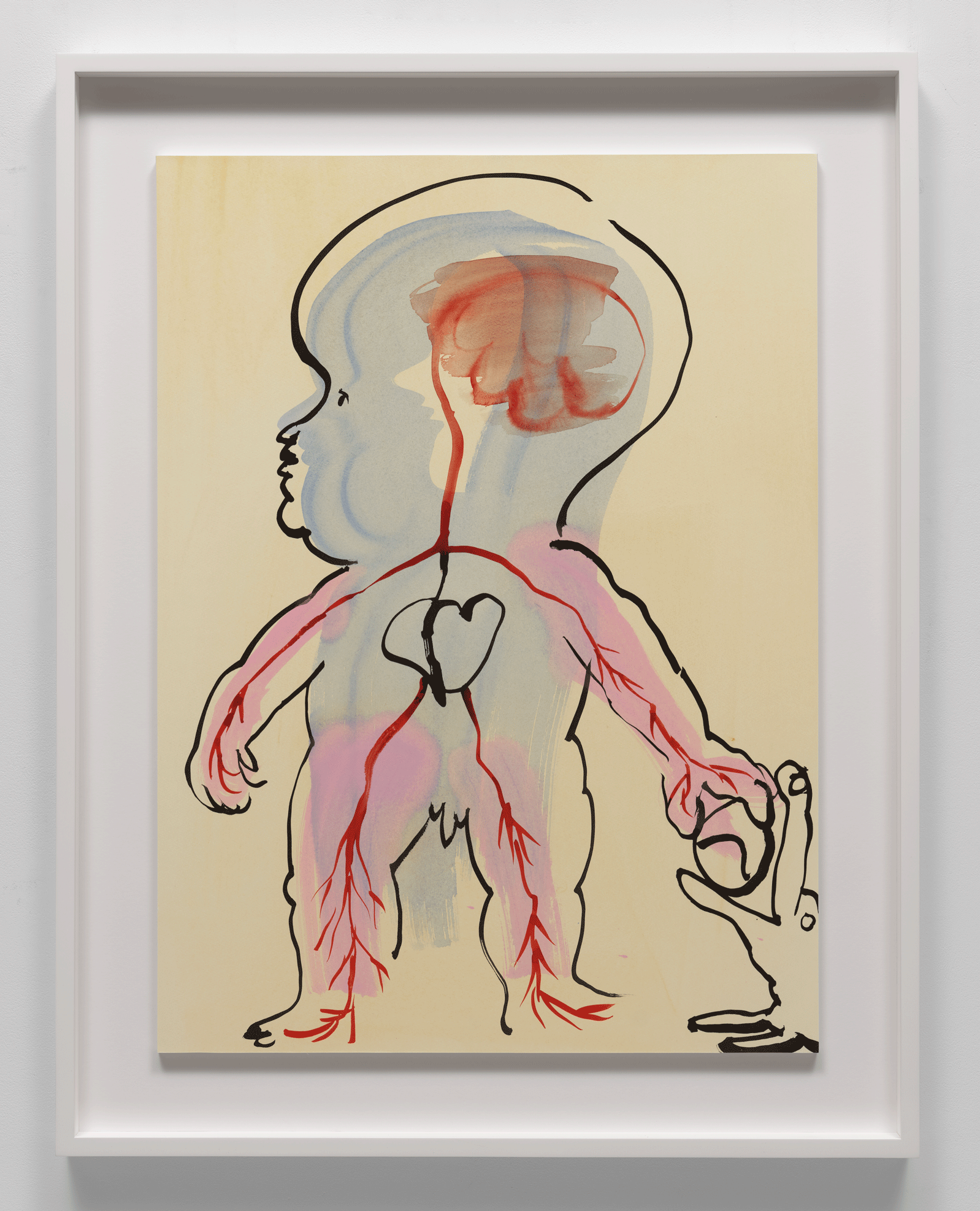

GALLERY

to see more

Our Voices

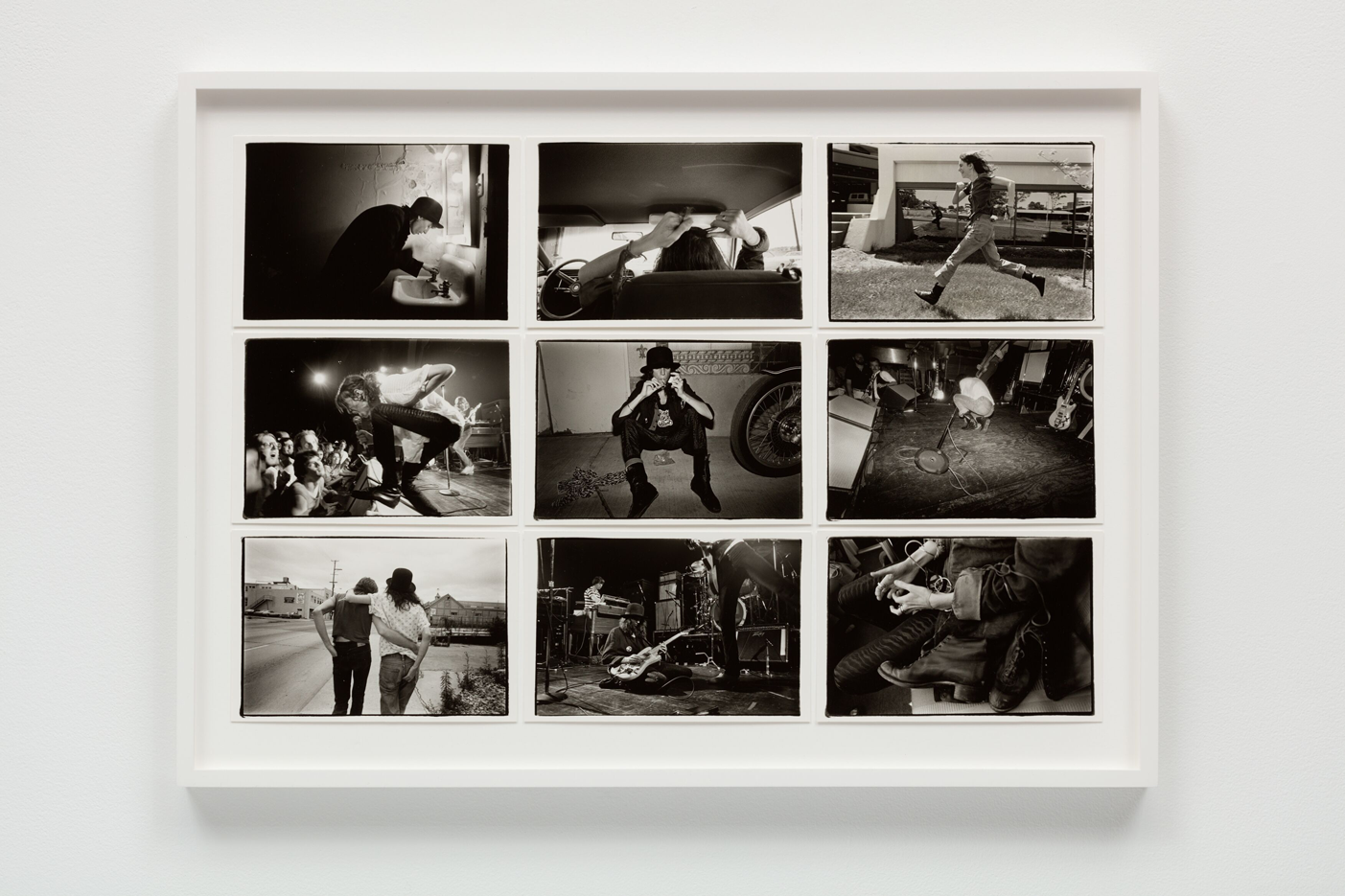

Annie Leibovitz is a legendary portrait photographer whose work captures the intersection of intimacy, theatricality, and cultural history. Known for iconic images like Demi Moore: More Demi Moore and John Lennon and Yoko Ono, her career spans decades of documenting the human experience through the lens of storytelling and visual artistry.

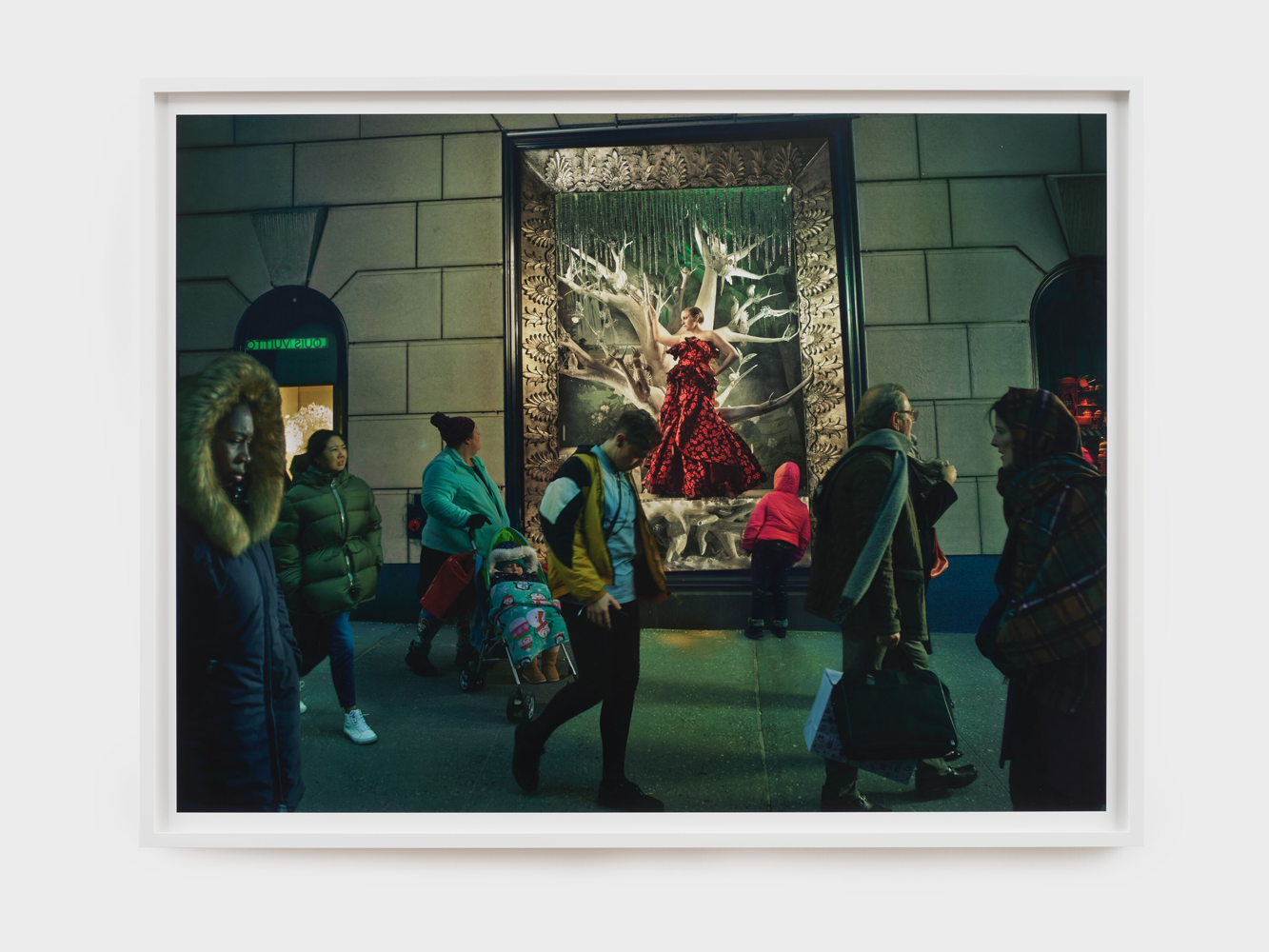

Amy Sherald is a celebrated painter whose vivid portraits reimagine identity and American culture. Best known for her iconic portrait of Michelle Obama, Sherald’s work combines emotional depth with luminous color to explore narratives of Black identity and collective memory.

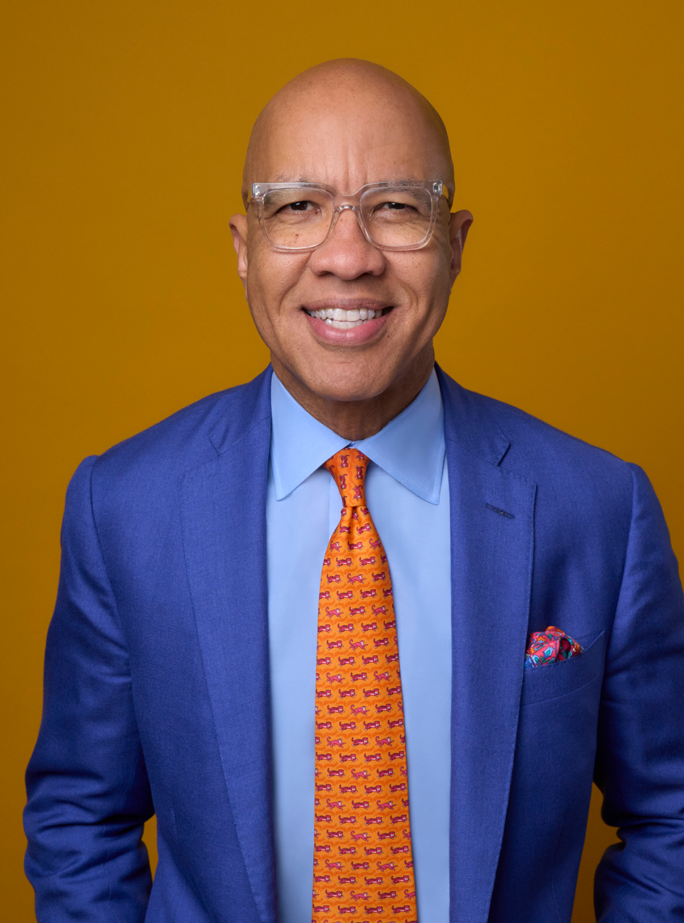

Darren Walker is the president of the Ford Foundation and a philanthropist dedicated to advancing social justice. Under his leadership, the Ford Foundation has redefined modern philanthropy, focusing on equity, inclusion, and progress. He serves as a director at the National Gallery of Art, where his passion for the arts aligns with his mission to promote cultural equity.

Explore Other Episodes

with

dream hampton

Listen Now →

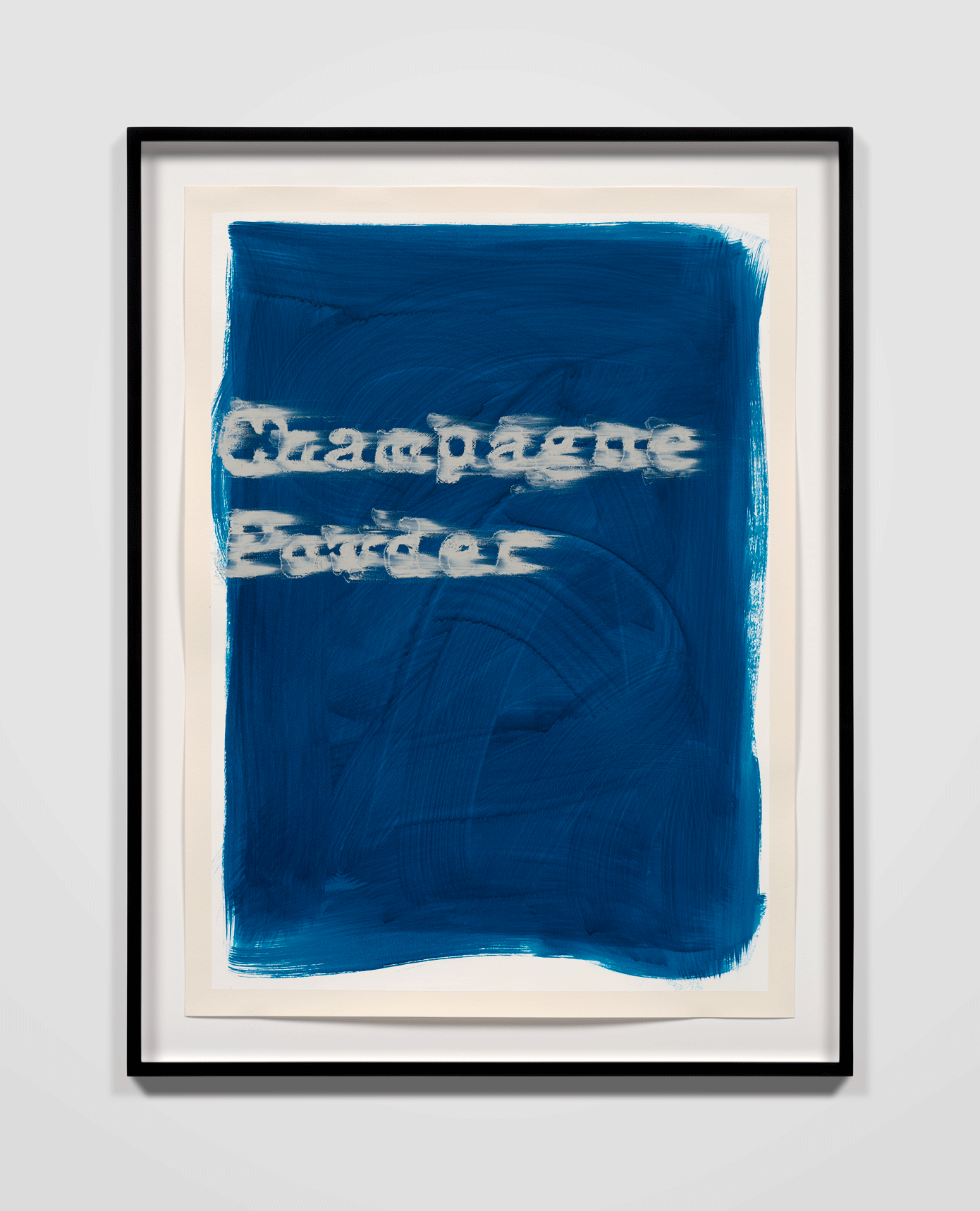

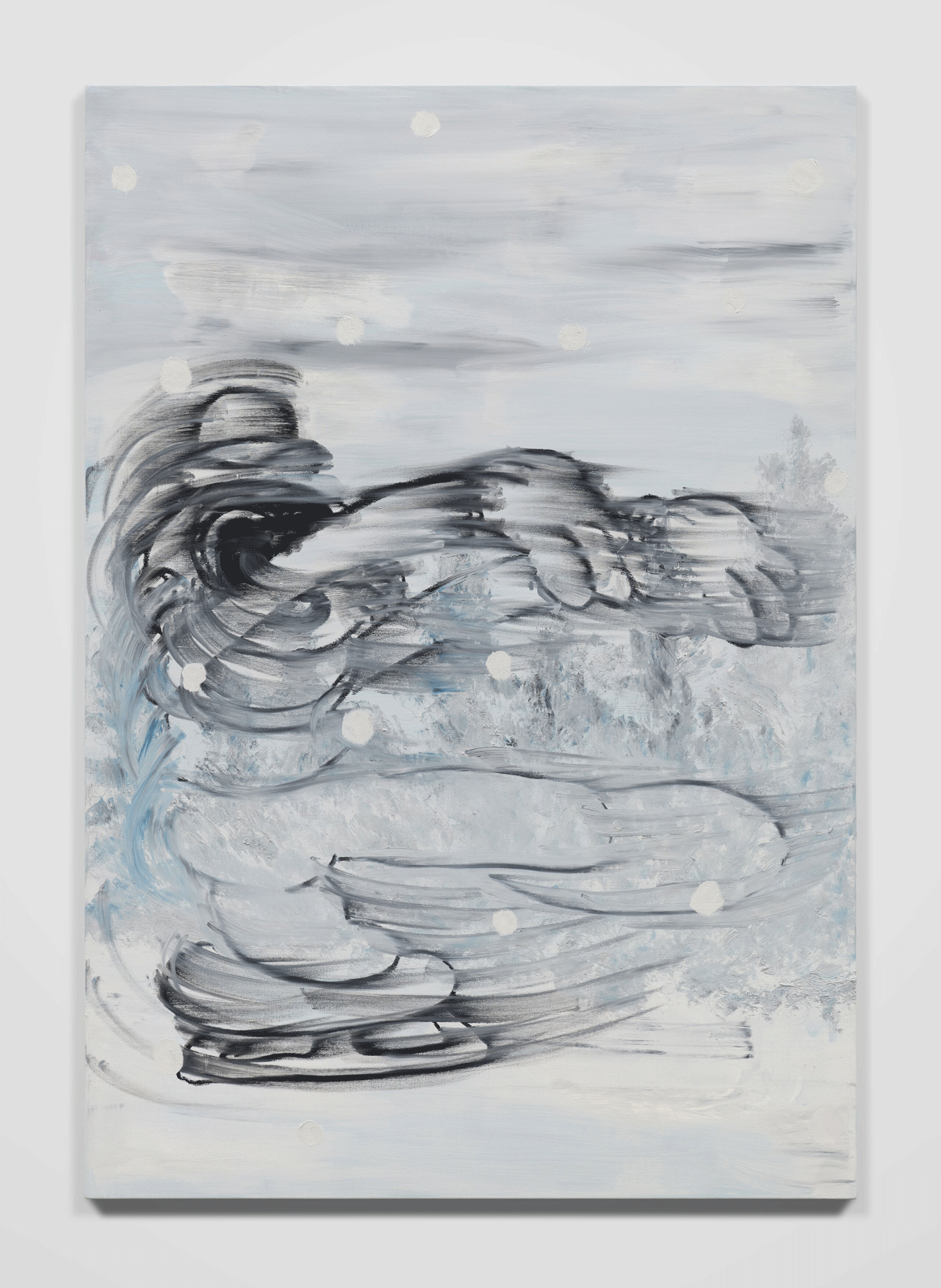

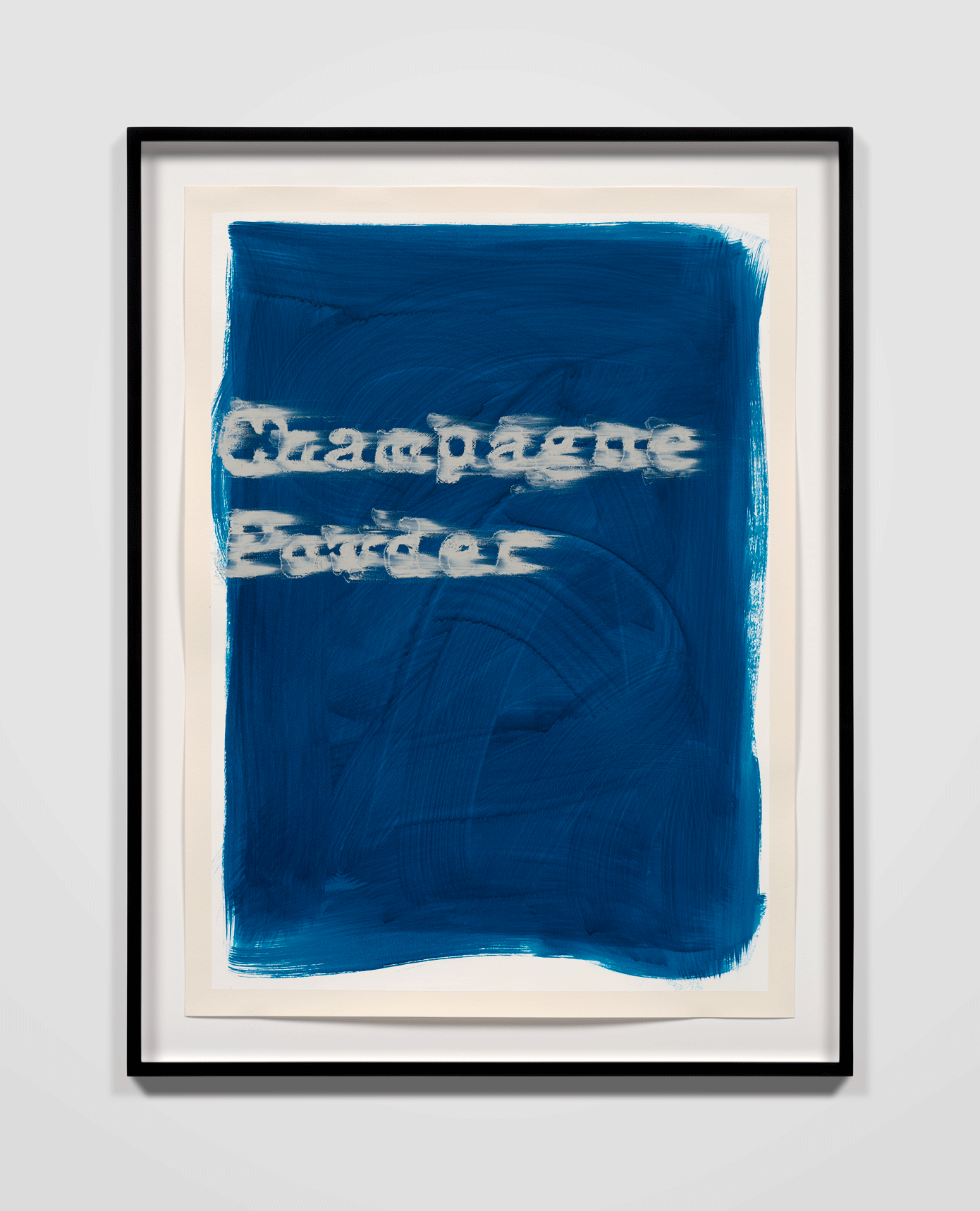

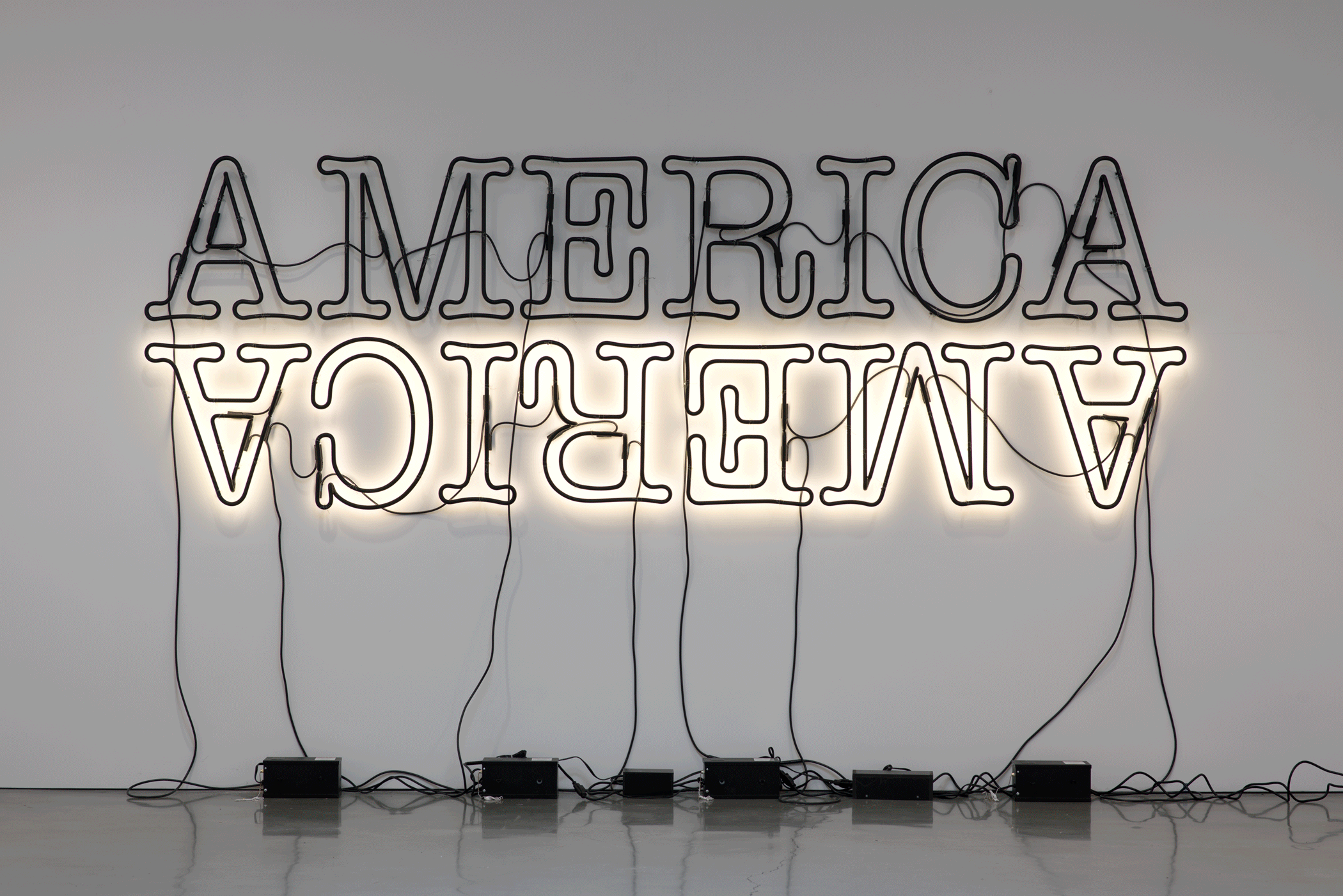

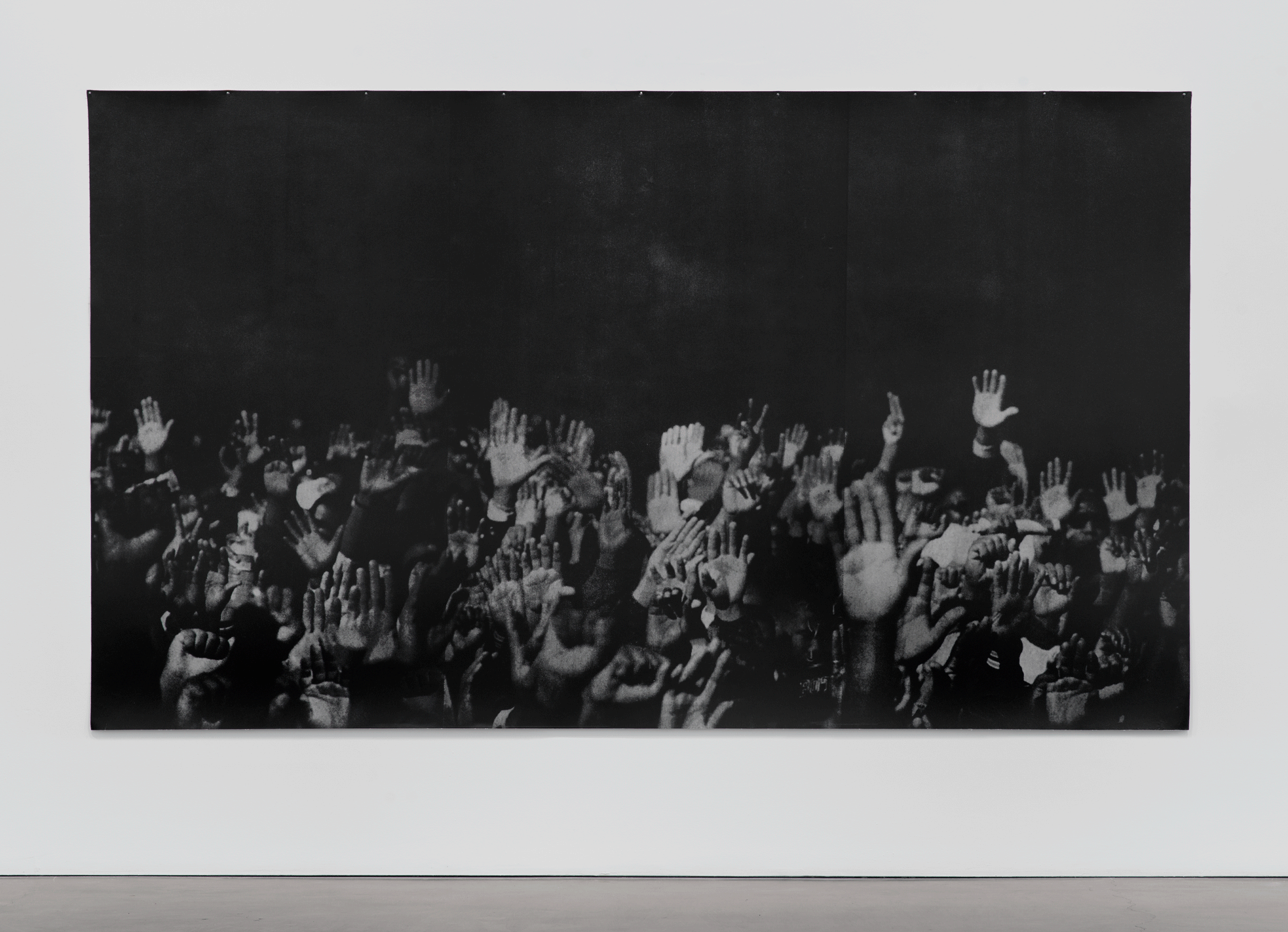

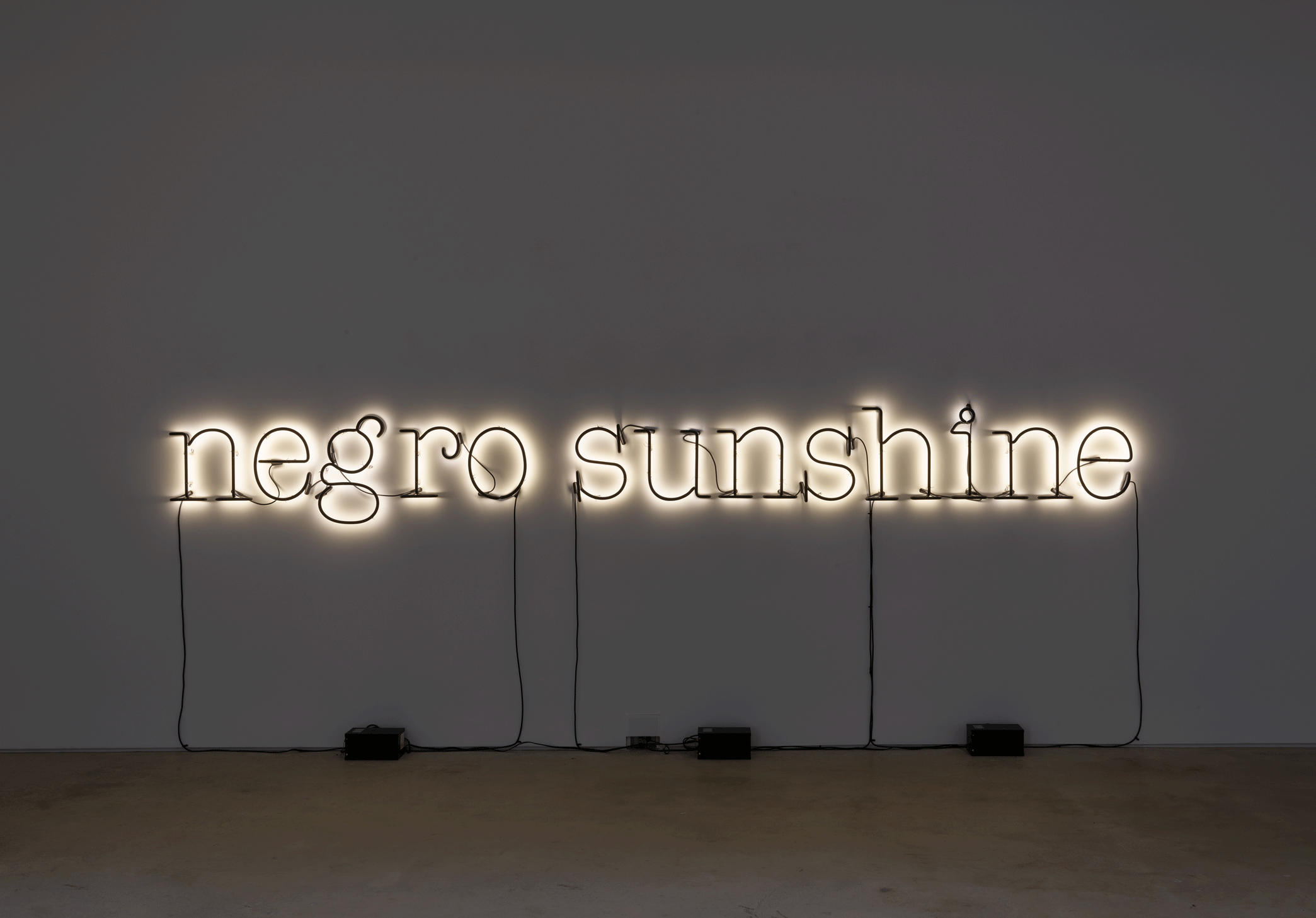

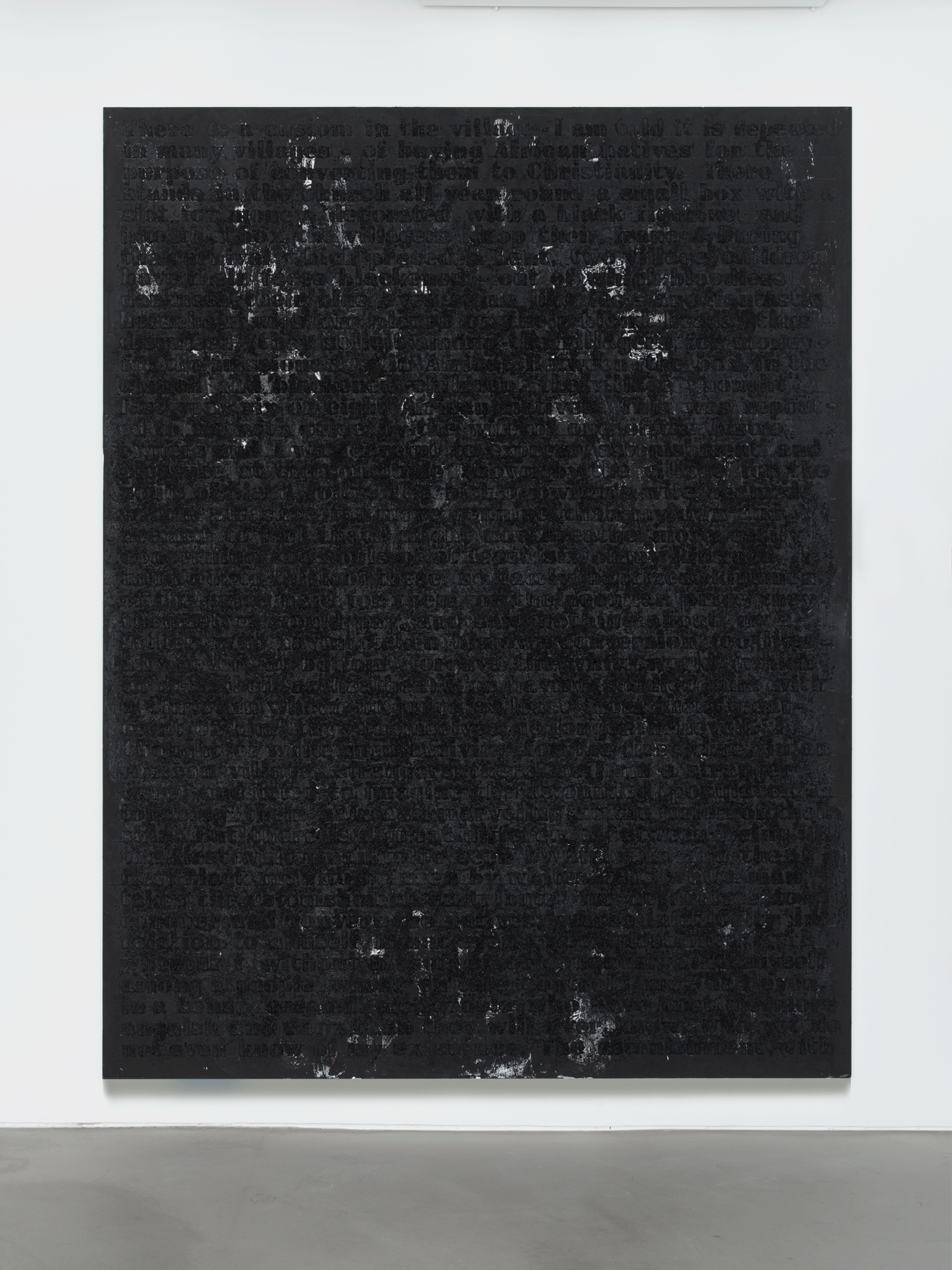

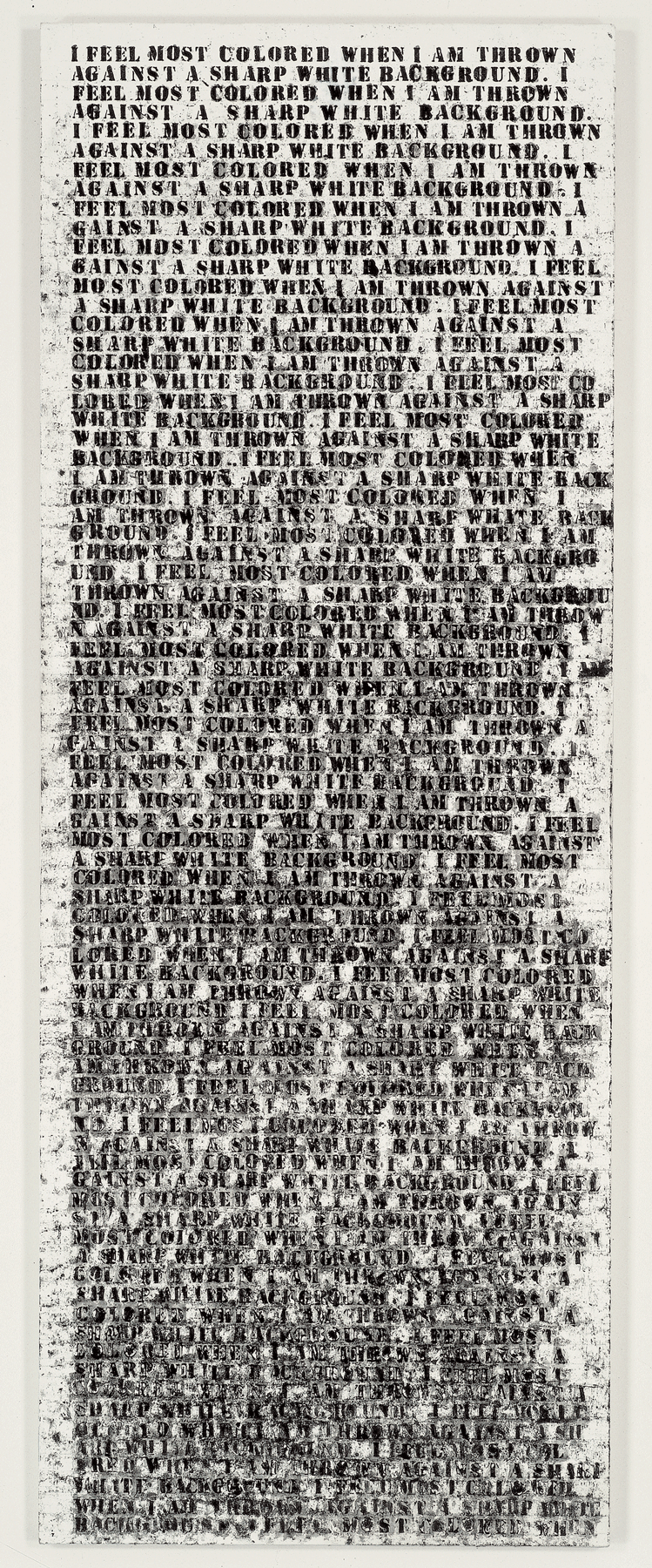

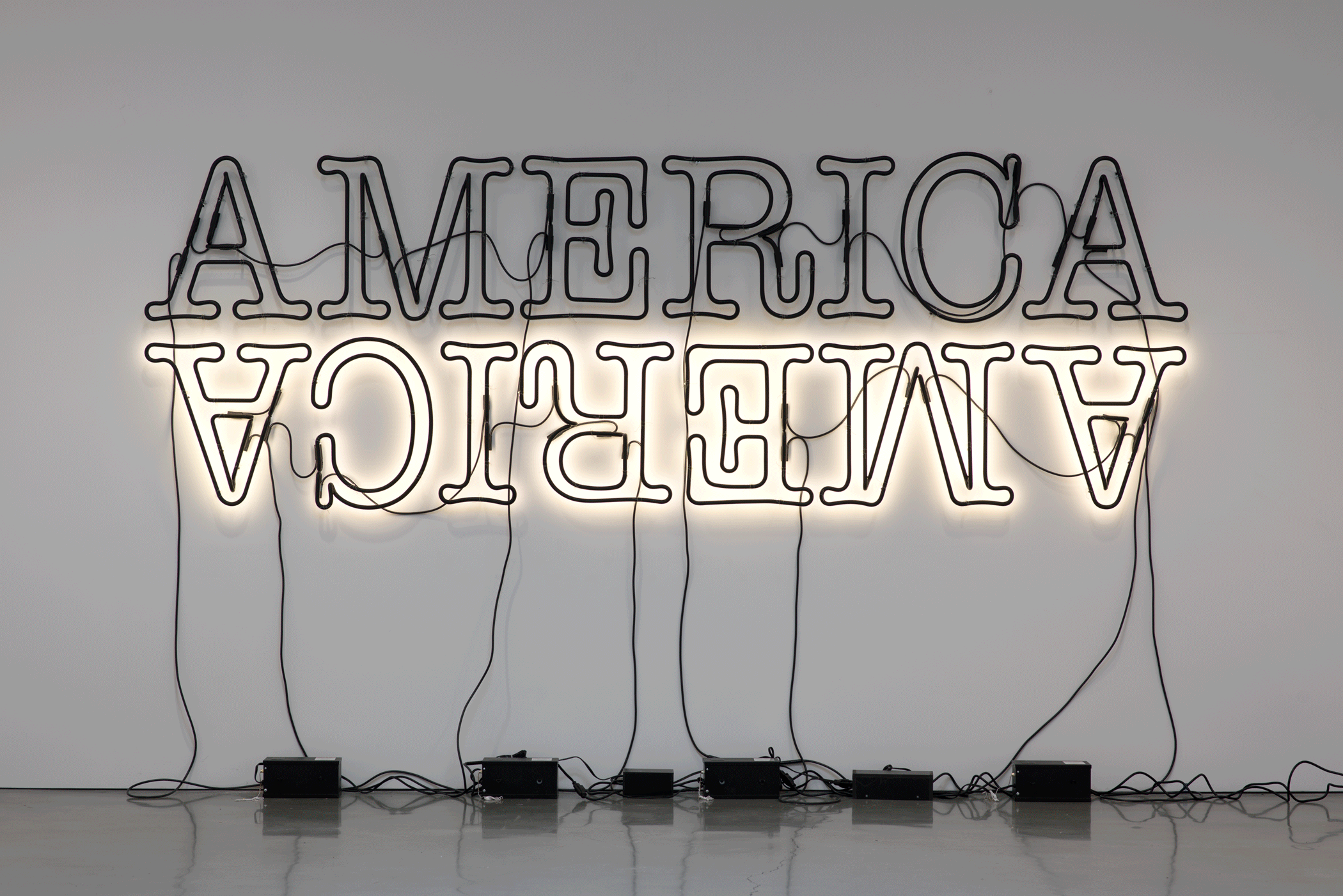

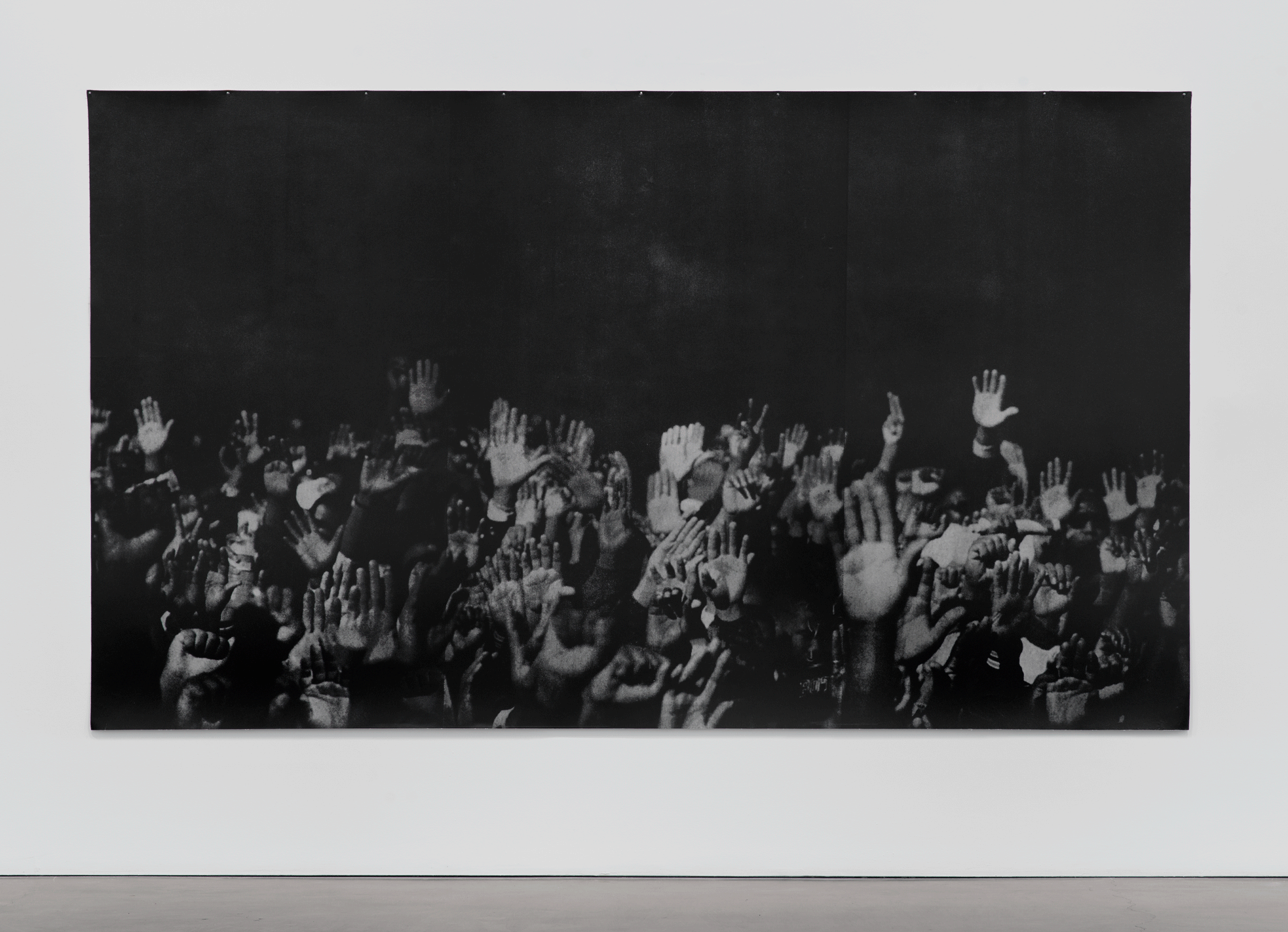

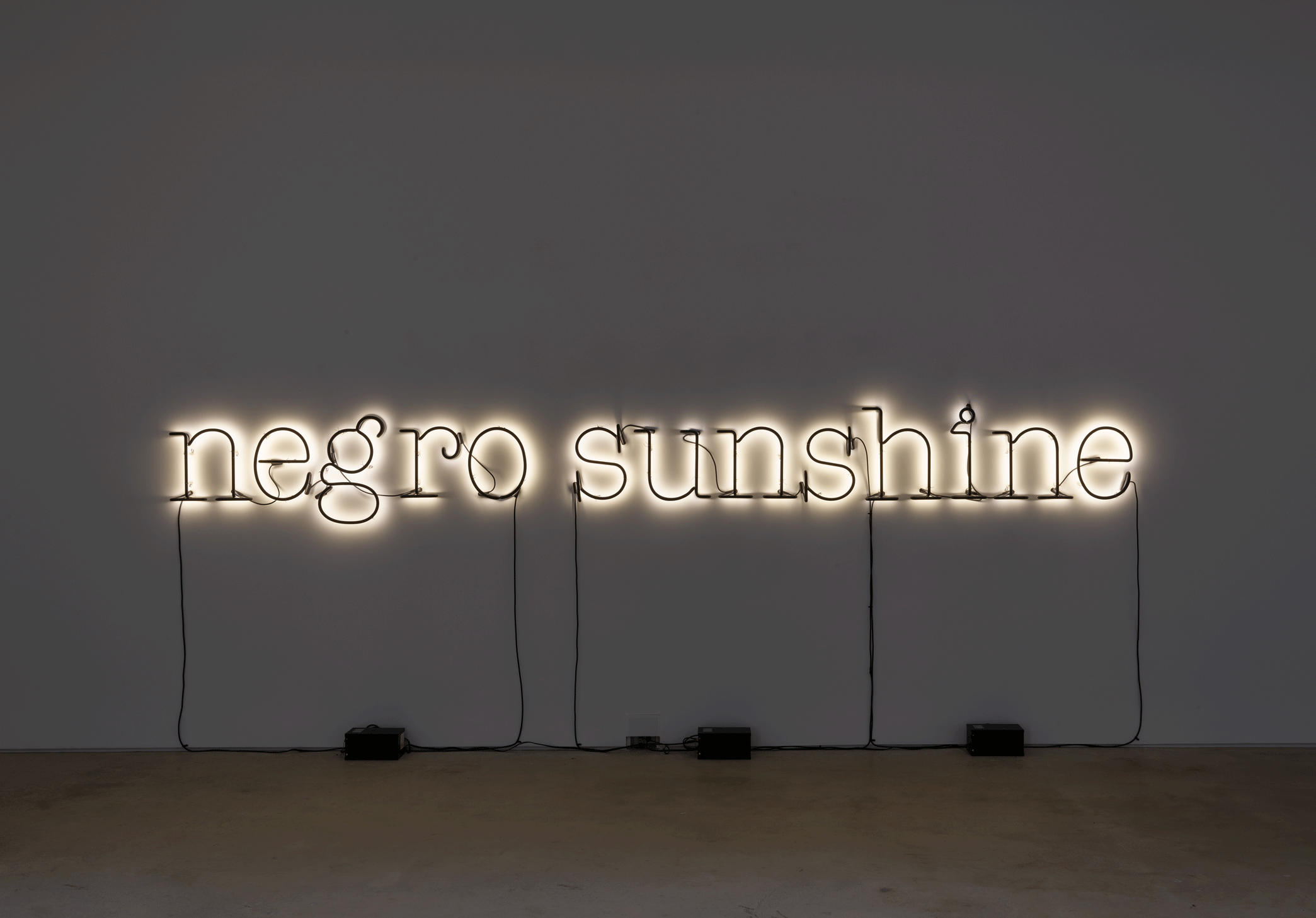

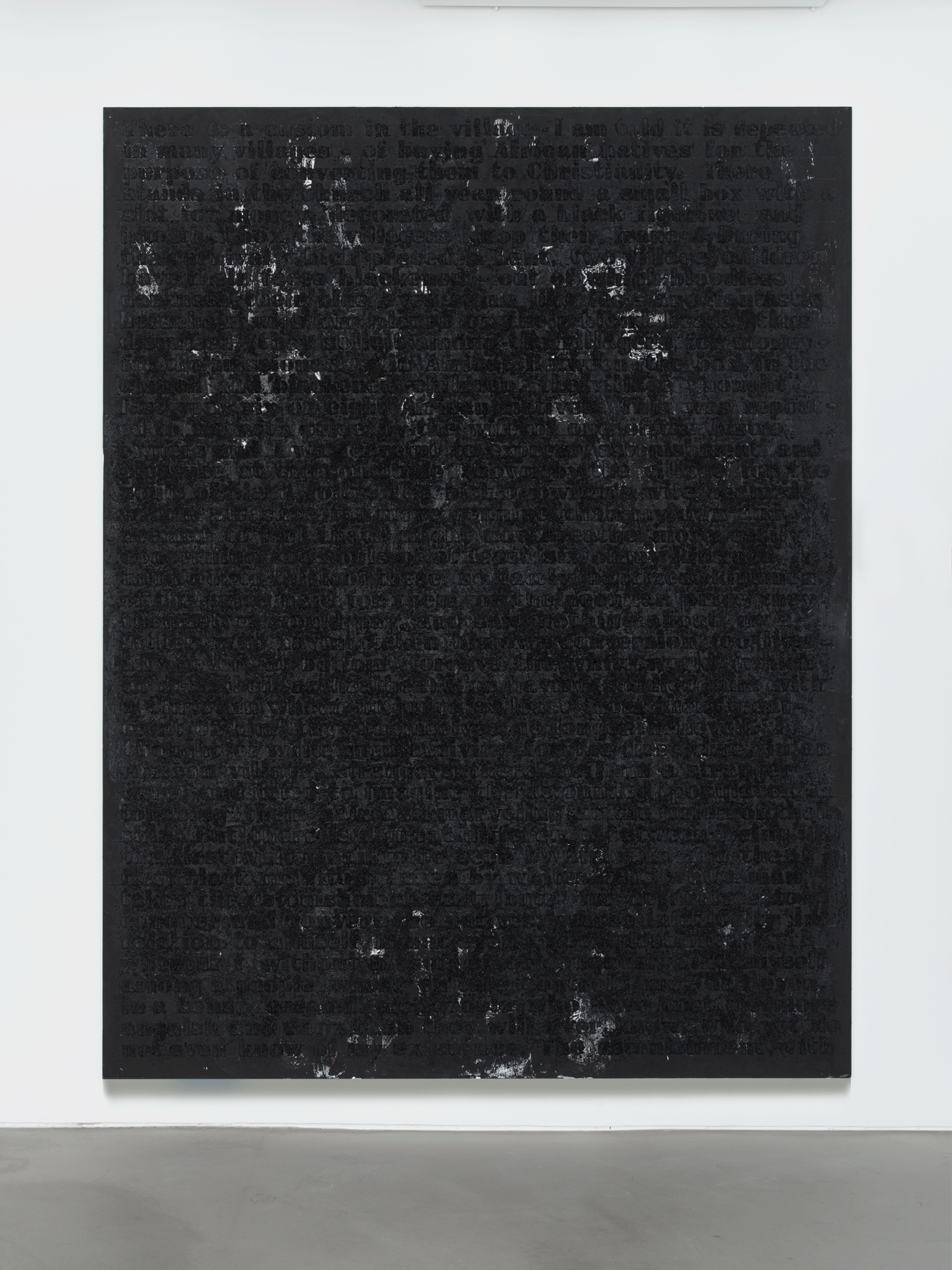

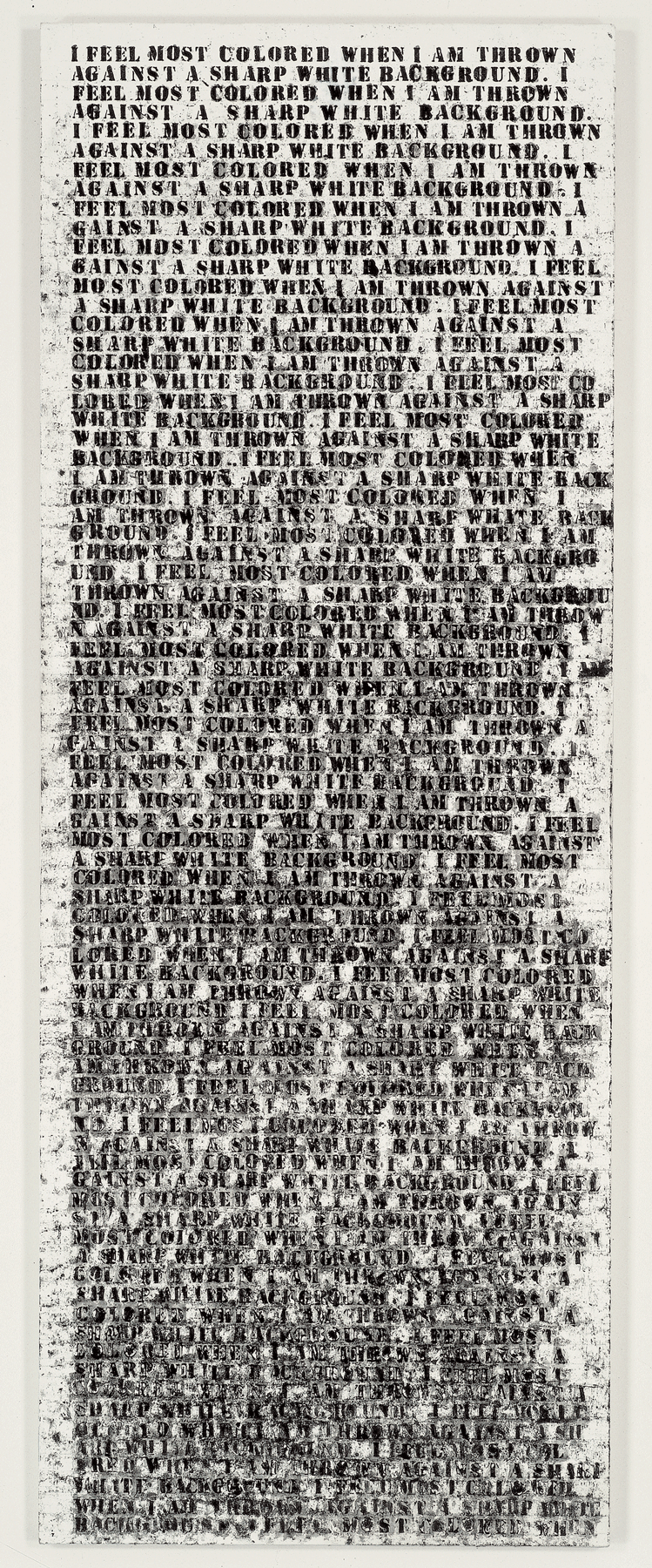

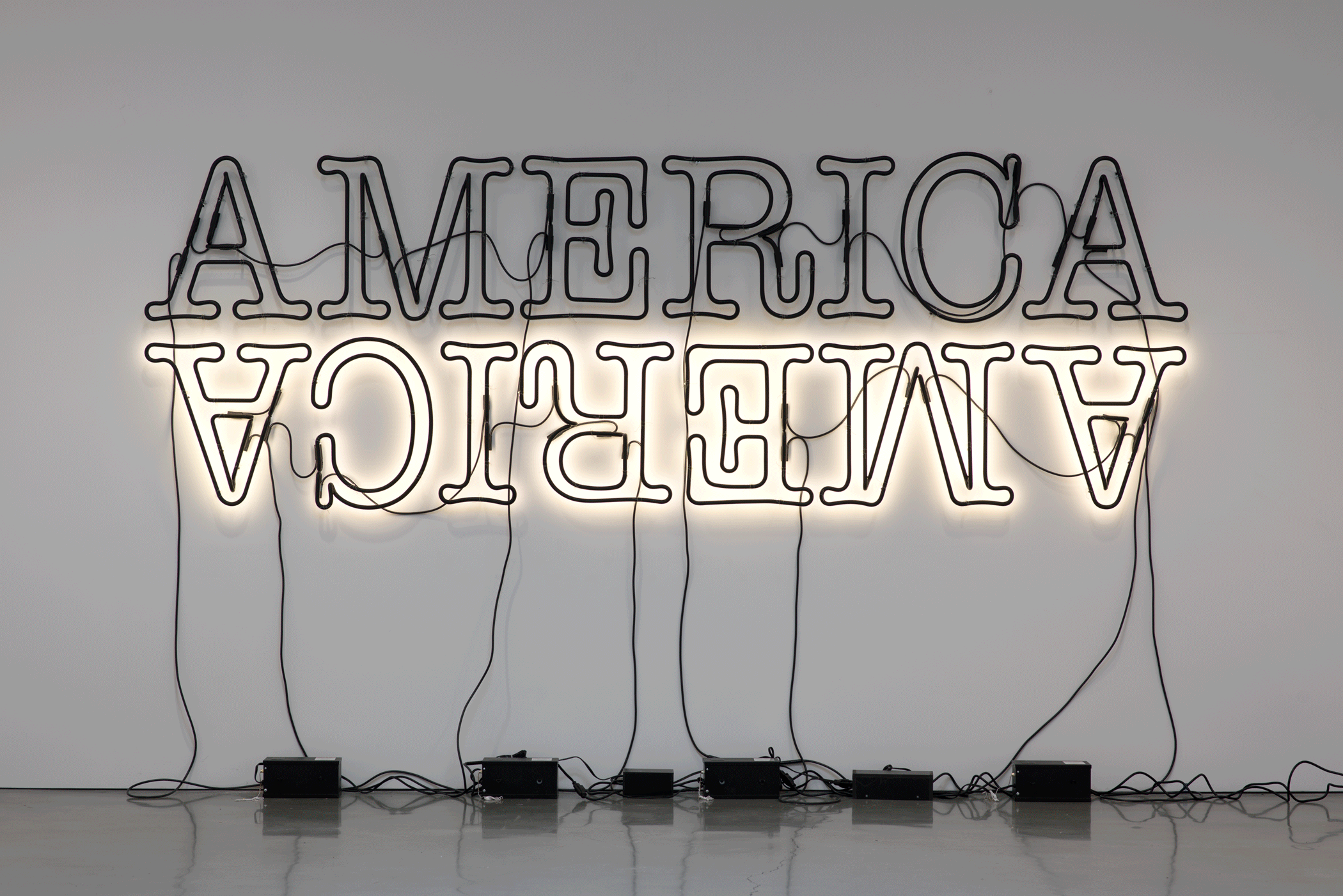

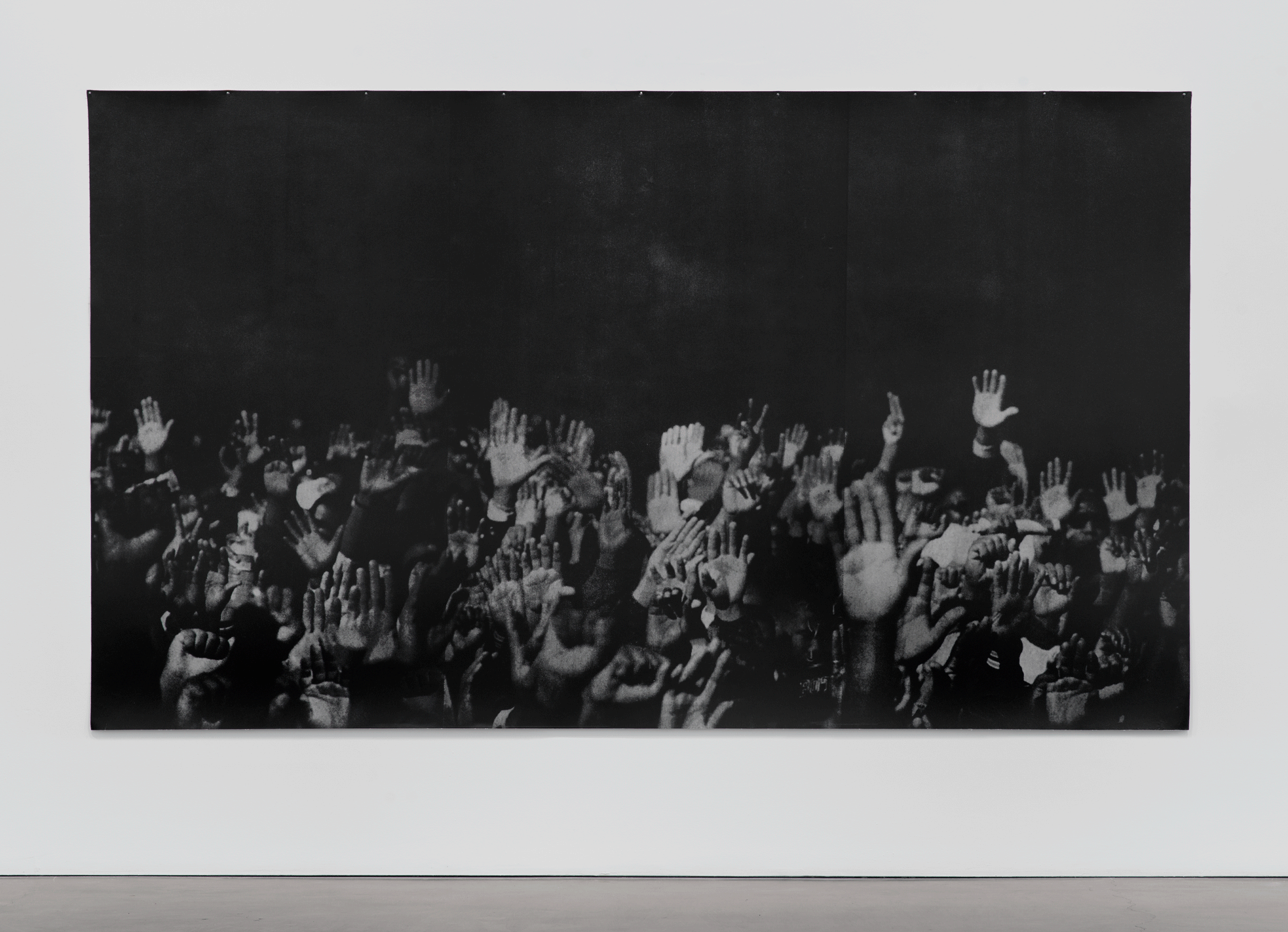

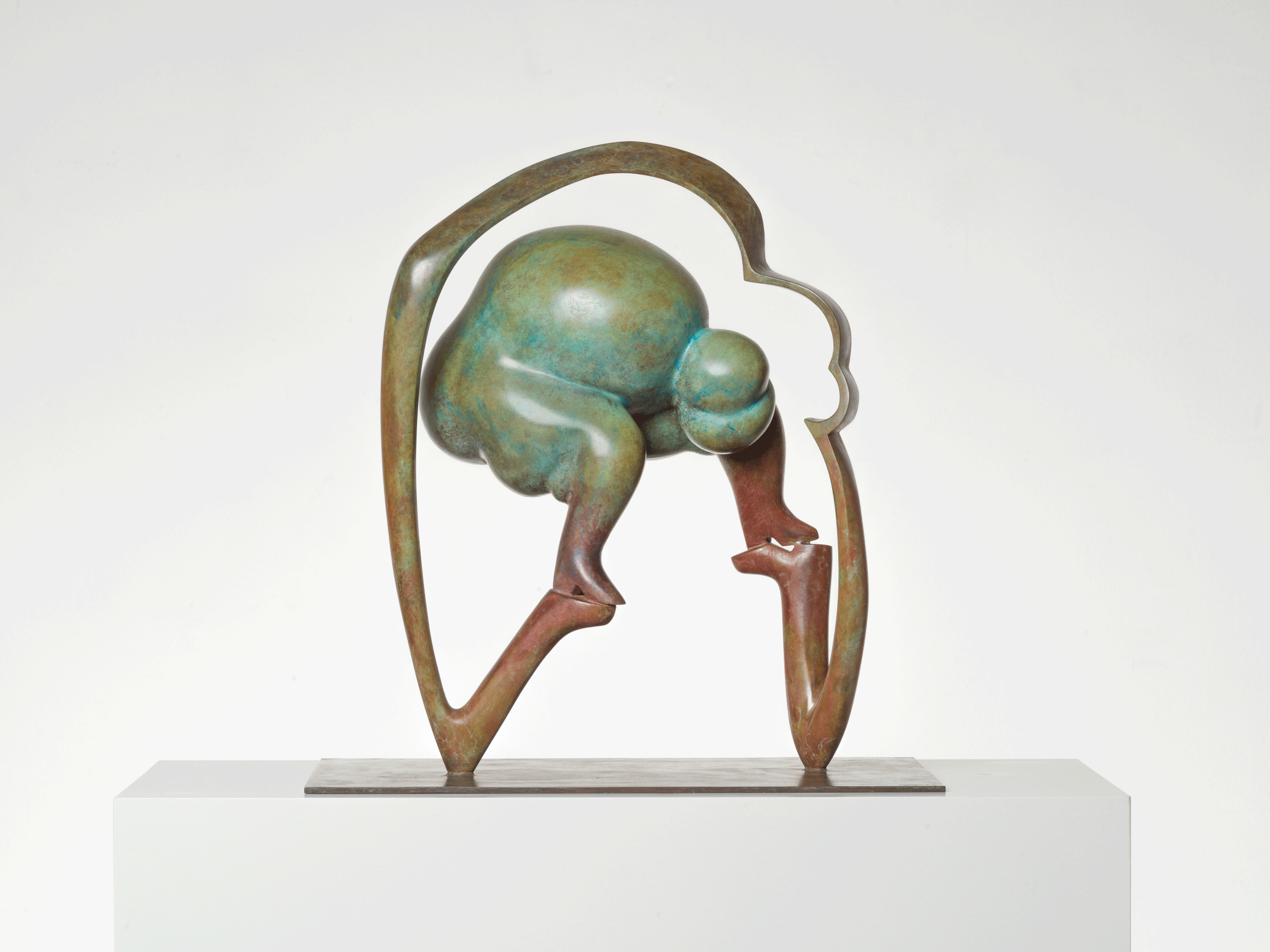

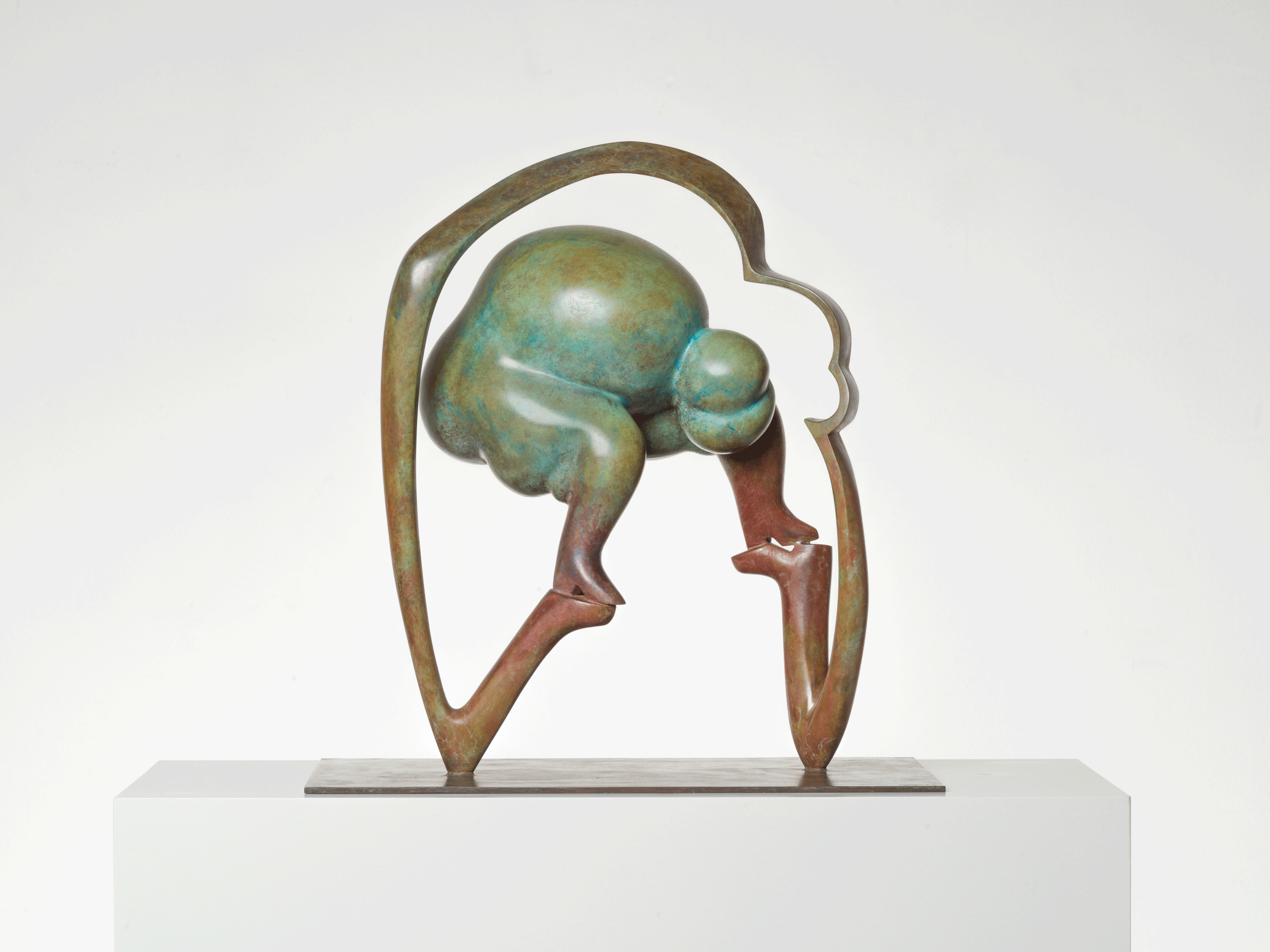

Gary Simmons

with dream hampton

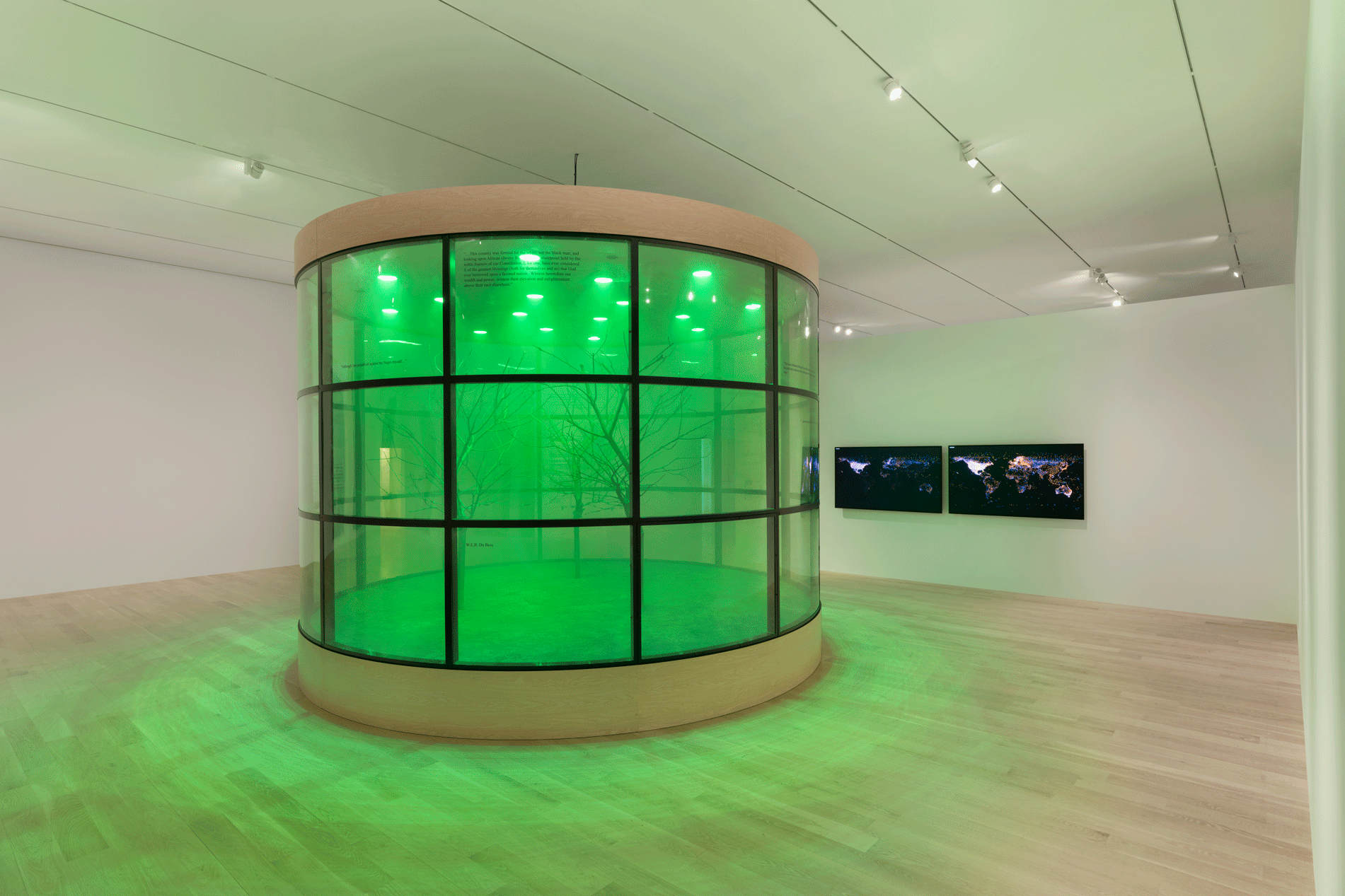

MEMORY examines how personal and collective recollections shape our identities and histories, inviting us to reflect on what we choose to remember—and what we forget.

In this episode, artist Gary Simmons and filmmaker dream hampton delve into the ways memory shapes our identities and our collective histories. Simmons reflects on how cultural memory—particularly through race and erasure—has influenced his work, from his iconic chalkboard drawings to his installations that blur the lines between representation and abstraction, while dream hampton offers insights into the silencing of certain memories and the power of remembering and reclaiming erased narratives. Together, they reflect on the personal and societal implications of memory, how it shapes art, and how art, in turn, redefines our understanding of the past and future.

Edge of Reason, Season 2 | Memory

SECTION ONE | THE THEME

Jeff Chang Welcome back to Edge of Reason. This season, we’re shifting from Enlightenment-focused ideas to something more personal, exploring the big ideas and forces that shape art and life. Memory, perception, attachment, and the magic hidden in everyday moments. These are some of the themes we’ll dive into, themes that touch both the individual and the collective, where logic meets creativity, and where art helps us make sense of it all.

In today’s episode, we begin with memory. Memory can haunt us, soothe us, or even elude us. It stirs nostalgia, puts us at ease, or reminds us of what we’d rather forget. Some memories we create together, shaped by shared experiences. While others connect us to people, we’ve never even met. How fluid or fixed must memory be to hold power?

What happens when some memories are best left forgotten? And how does memory influence who we are, both individually and collectively?

These are the questions we’ll explore at the Edge of Reason.

<< Theme Music >>

Jeff Chang …a limited-series podcast produced by Atlantic Re:think—The Atlantic’s creative marketing studio—in partnership with Hauser & Wirth—a home to visionary modern and contemporary artists.

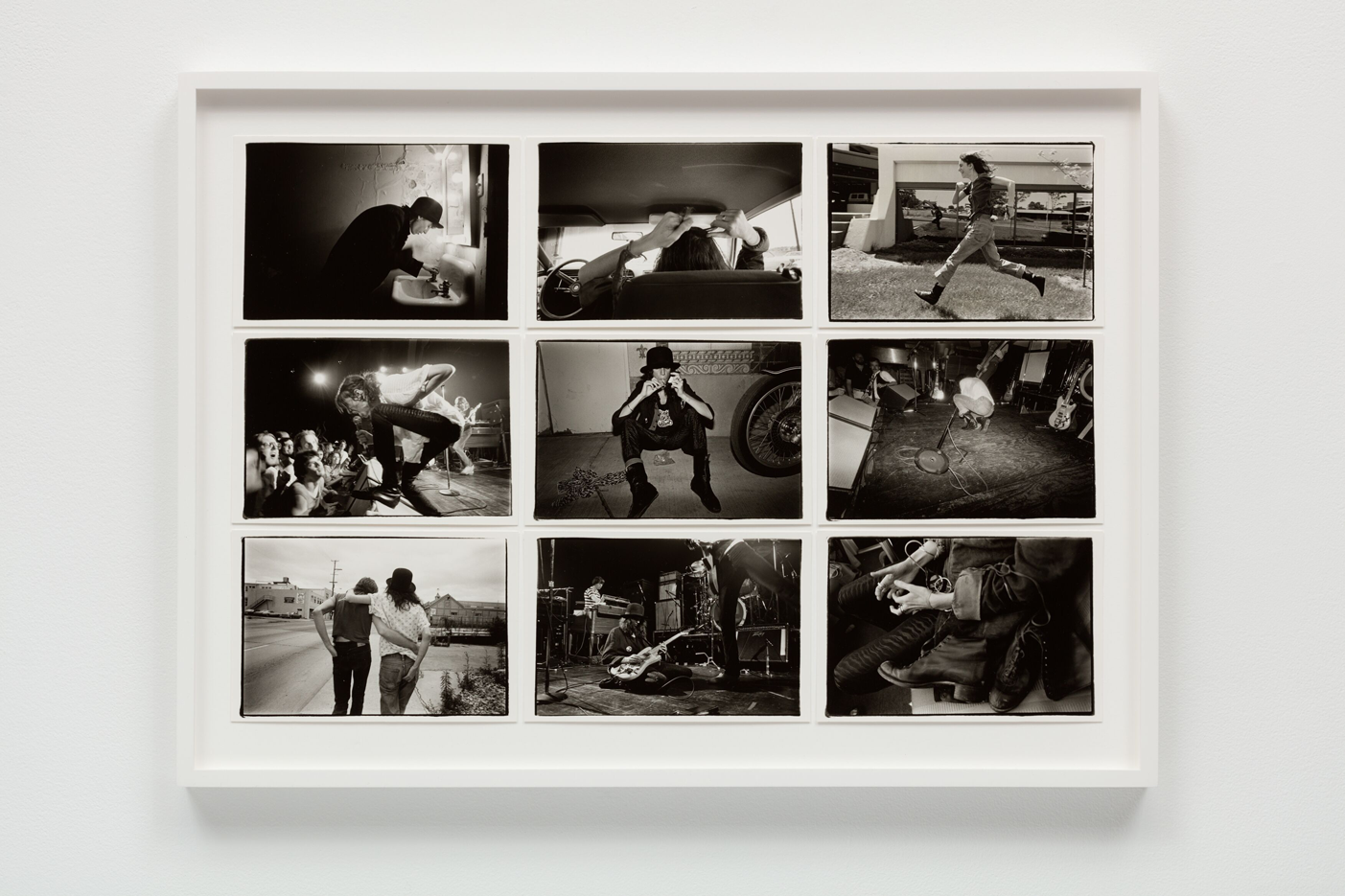

Joining us today are two visionary artists who explore the complexities of memory. In the late 80s and early 90s, Gary Simmons made a name for himself with his erasure technique, using blurred images to investigate race, history, and cultural memory. Dream Hampton, a groundbreaking filmmaker and writer, captures both personal and collective memory in her work, shedding light on forgotten stories of survival and justice, highlighting the true power of narrative.

Together, they offer powerful insights into how memory influences art and how art can shape our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. And I’m lucky to call both of them friends.

SECTION TWO | THE ARTIST

Jeff Chang Gary, I’m so excited to dig into this with you. Welcome to Edge of Reason.

Gary Simmons Jeff, thanks for having me, brother.

Jeff Chang Today, we’re diving into memory and shared memory. And you and I both came up as hip hop heads, uh, around the same time, even though we didn’t meet up until much later. And I remember first encountering your work. It might’ve been Line Up, that piece that you did, the installation with the gilded shoes on a platform in front of a mugshot gallery.

Or it could have been your early erasure drawings where you had sketched out cartoon characters that were rooted in blackface, like, like Mickey Mouse, right? And then you erased them on chalkboards. And all I know is your work gave me chills. It was like this bolt of recognition where it was like we shared the same memories.

Uh, but for our listeners, I’d love for you to unpack this. Where did those ideas for those pieces come from, and how do you approach memory in your work?

Gary Simmons You know, I think that I’d have to go back a bit to my undergraduate years. I was fortunate enough to go to the School of Visual Arts in New York and Cal Arts in LA, and the foundation of my education was really a lot of minimalism, a lot of conceptualism.

Most of it was through a kind of white male Lens at that time. And although I was drawn to it, I never felt like there was a me in there. I didn’t feel like my voice was being heard through minimalism and conceptualism. I started drilling into the history of education and black kids and public school and where we learned.

And the earliest forms of memory that I can think of and education combined was cartoons. Those images left a massive impact for me. Um, but when you start to look back and critically deconstruct what it is that we were looking at, that’s where it became very interesting, you know, it was embedded with a lot of very racist imagery.

So one of the earliest is probably Disney. So I was looking at things like Dumbo. And thinking back about, you know, here’s this little elephant, has this shortcoming, so to speak, of these gigantic ears, and he gets taught how to take what’s perceived as a negative and turn it into a positive. What’s interesting about it is that the characters that teach him to use that shortcoming for his benefit are blackface crows.

And I started to realize that the memory of that cartoon started breaking down along racial lines. So, you know, thinking about the blackface crows, black folks remember those crows completely. And non black people were looking at the cartoon and thinking about just the elephant. And so I started to dig deeper and try to find race cartoons.

That’s where that started to come about was how we track our memory, how we break down things that we’ve seen and recall and the snatches of information. that are lost in between the reality and the perception. And therein lies that blur that my work sort of hovers. It’s sort of between representation and abstraction.

Jeff Chang I know that theme has been a continuing through line in your work, and I wanted to ask, what were you hoping to achieve, or what are you hoping to achieve with the meaning of these images, uh, by blurring them or erasing them as you do?

Gary Simmons What happens is when you’re a young artist, you’re trying to make a mark for yourself. You’re going to make these big statements. You know, and I think there were a lot of things at the time that I could draw on. It was a really rich time visually and culturally, and hip-hop was starting more or less. And I started to pick up on the idea of sampling and cutting back and forth. Where you’re taking this kind of soundscape and creating something different.

And that application went into literature, music, fashion, art, all of that. If you were probably downtown or in LA or Detroit or wherever, and you were a young kid in the city, those images, those sounds, those things spoke to you. You know, that was the first time that you’re up there and it’s like, that’s us.

There’s a strength in that.

Jeff Chang There’s so much to impact there. And we’ll dive into some of those questions shortly, but first, let’s welcome our guest dream hampton. dream, originally from Detroit, is an acclaimed filmmaker and journalist. She started out as one of the few women involved in early hip-hop journalism, working in music, culture, and politics.

She’s gone on to produce and direct Surviving R. Kelly, which earned her a Peabody Award. Her recent work includes Freshwater, and It Was All a Dream. Among her many accolades, she was named one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People.

SECTION THREE | THE GUEST

Jeff Chang: dream, my old friend, welcome to Edge of Reason.

dream hampton Thank you. I’m so honored to be here with both of you.

Jeff Chang Your work from writing and organizing with Black August to your films, your filmmaking, has always focused on uncovering silent stories. I’ve heard you mention this before—cultural amnesia. How do you define that? And what does it mean to you?

dream hampton So erasure, right, is, um, I often talk about this as a black feminist praxis, right?

It’s citation, right? We’re constantly having to put ourselves back in a history. So doing things like putting Cindy Campbell back in this story, and that has since been contested, but whatever. Like, so Kool Herc’s sister who throws the actual party that we call the beginning of hip hop is a perfect example.

Even just the history of women in hip hop period gets erased. I saw something: Tony Hawk is holding his grandson and apparently, the grandson is his son’s kid, with Francis being Cobain, and the tweet was saying Tony Hawk and Kurt Cobain are the grandfathers, and I was like, wow, Courtney Love can get erased too.

Like, you know what I mean? Like, and she made herself enormous, you know, but it’s… so, so women are always in danger of being erased. It’s just how it is. It’s the truth of like patriarchy and the insidiousness of it and the everywhere ness of it.

Jeff Chang If I may, I wanted to quote Gary here, who talks about memory.

Uh, you said once, I think of memory as more than what we are willing to tell ourselves. It’s also composed of our refusals, our failures to account. With that in mind, dream, I wanted to ask you, what responsibility do you feel towards memory, particularly those memories that are silenced or ignored? How does absence or silence play a role in your work?

dream hampton We’re always racing against time and the bandwidth that we have to like, remember and keep people in our histories, to keep it alive and So, you know, I’m thinking about like this Black feminist generation that so shaped me that we’ve already lost Toni Morrison and Tazaki’s still here. But, you know, um, I just saw June Jordan and Audre Lorde’s notes around Palestine become this huge, um, talking point.

I was thinking about how we’re projecting a today’s politic onto their moment, but that moment wasn’t that far away. It was the 80s and sadly so many of the issues remained static. So I was thinking about how these questions. are at once, like, a history and a present and a future. Um, and sometimes the players are just shifting.

So the questions remain the same. In my last documentary, the questions of misogyny, the questions of erasure of women, the questions of when and where we enter this work and how we criticize it, they all remain the same. So, I mean, I don’t know what the work is. I always say that I want problems worth having, and that usually means new problems, right?

Like I, back to hip-hop, like Fat Man Scoop dying on stage, or Elvin Jones, you know, great drummer. dying in the morning after a gig, right? I don’t want to spend my, like, last breath arguing with some rapper about misogyny, right? Or any man, right? So, there’s that work, and then there’s that exhaustion from that work.

Some of it is memory, but some of it is still right now. And sadly, like, the future that we face with the same problem.

SECTION FOUR | THE CONVERSATION

Jeff Chang Let’s bring both of you in the conversation. Now, Gary, as you’re listening to dream, what’s coming up for you?

Gary Simmons I mean, I agree completely with what dream’s saying. I think to add to it, I think not all memory sits in that glow of amber light. I think that sometimes memories are painful and create certain traumas for certain people, and it’s how you deal with that moving forward, right? And so I think colored folks have a long history of needing to reinvent certain histories. I think that there’s, because we’re oral historians in a lot of ways historically, right? There wasn’t things written down. There was things that are passed down and how that, you know, it’s almost like a game of telephone where I tell dream something and then she tells it to Jeff, and so on and so on.

The basis of the story stays the same, but there are little nuances. Or, you know, even if you get into something where you translate material from one language to another, there’s slippages and loss between those two. And I think that you’re, that our memory works in a similar way. The further we move away from an event, the blurrier it gets. And there’s a kind of desperation to to complete the gap between the actual and what we’ve now sort of preserved. I don’t think, you know, to use dream’s word, I think it’s extremely fluid. It goes back and forth, and there’s ebbs and flows and things like that that we’re forced into completing.

I can remember sitting in the kitchen, and I idolized my grandmother. She was my everything. And I would watch even the way that she moved through the kitchen. And, you know, she’d be making codfish cakes or something, and nothing is written down. So I’d say, “Gram,” you know, “How much pepper or scotch bonnets do I put in for that?” She’s like, “Oh, sweetie, you’ll just know. And, you know, you just kind of sprinkle it in.” And I’m… I’m like, wait a minute, yeah, like I gotta get this down so that I could make this for my daughter and her kids and so on. She’s like, oh yeah, you’ll just pass it on.

And I think there’s something really beautiful that the meal kind of subtly shifts, but somehow in our memory, our grandparents have that perfection that they always get the meal right. And I think as a boy child in this household full of women, very strong women, West Indian women, you know, that oral history passed down is essential.

There’s this photograph that I talk about, that’s me and my sister in the backyard. I think my sister’s in her diaper or something, you know. It’s like nineteen, late 1960s, early 70s or so. I’m aging myself, obviously. And I have one of those little tin pedal cars that we all had. And my grandmother must have told me what was going on in that photograph probably a hundred times before she passed. Now, what’s interesting about that is I can’t really, truly recall what happened. But the retelling of that event has become so like, like part of my own history.

That her recollection of that photograph has become my memory. And I think that that’s a really fascinating thing to deal with. And it sort of represents the way all of us have grown up with that way of how we deal with recollection, even if it’s once removed. And somebody’s retelling you the history that you went through, and you have to respect this, and you have to respect that.

Jeff Chang You’ve touched on so many things here. First, the impossibility of memory. the need to fill a kind of a vacuum and then how the artist takes memory and brings it forward. It actually makes me think of this line from Freshwater dream, like where you have that beautiful yet devastating line from your grandmother about water never stopping and I’m getting chills just thinking about it, but this idea of water always moving.

Uh, and then you show these powerful images of your family in the flood and you talk about how the floodwaters consume your memories and that a flood is water that can’t move, that is not allowed to flow.

So as you listen to Gary’s reflections, uh, on memory, what comes up for you and maybe for both of you, what role do you think the artist has in shaping memory for the present and, and even for the future, like for your kids and for your grandkids?

dream hampton Well, something that struck me that Gary was talking about is actually a lesson, like, as I now have an adult child, and nieces and this idea of the photograph, right? Which becomes kind of a shared family memory, but really there’s someone who’s dictating it. Or the photograph, we don’t actually remember the birthday party.

We remember the photograph of the birthday party. So I’m also trying. not to be too prescriptive when it comes to the past, you know? The other thing I thought about when he was talking about the opposite of memory being in an amber glow, I was thinking about something I don’t talk publicly about often, um, just because it never feels that safe, but like, intimate and love relationships, you know?

And being older and having the distance and sometimes the wisdom to not judge them and cast them in the same ways. that I did when they caused me so much heartache or trauma, right? And, and in not like judging and casting the relationship in a particular light, I then free that person, that lover, from a memory that I associate with my own suffering.

And then it becomes a more generous exercise in like, what love is really supposed to be, which isn’t just about your own self. Like that kind of the ego way that we are constantly processing the world is through our own lens and our own feelings. I hate that, um, Maya Angelou quote, that it doesn’t matter what happens.

It matters how you felt about it. I’m like, no, it matters what happened, right? Although I know that to be true, I know that she’s accessing like a fundamental kind of truth about how we process. But then to give yourself again, not just like your lover the grace or your family member the grace, this also could be like love isn’t just our, romantic and, you know, sexual relationships.

It’s like you’re giving your parent that grace to know that the time that I actually, like, really judged my mom and hate her for failing or whatever, she was like 20 years younger than I am now. Right. And I still haven’t figured it out. Right. And the same obviously with our dads, you know, like, like, I, you know, all of the stuff that like, um, men are learning and relearning and have been forced to kind of reckon with, like, then to try to give some of the, you know, male figures in my life some grace, you know, um, so that has been an exercise that is connected to like, remembering and honoring.

And But it’s also like a rewrite or a remix. So it’s like crate digging, but the remix.

Jeff Chang I’d like to pivot here to talk about Greg Tate. For listeners who aren’t familiar with his work, He began as a writer at the Village Voice in the early 1980s and went on to define what would come to be called hip-hop journalism. Greg was a fearless writer, critic, and musician who was a dear friend and mentor to all of us. His sudden passing left us all feeling a deep sense of loss.

We memorialize him in our work, often asking ourselves, “What would Greg have done? What would make Greg say, ‘Okay, let’s talk about this’?” I think we all hear his voice in our heads, and it raises a bigger question about how we fill our memories and pass them on.

Dream, in Freshwater, you ask if the stories and memories we have today will still be around in a thousand years. Gary, if we knew the answer to that, how would we feel? What does it bring up for you, thinking about memory on such a long scale, especially as we honor Greg’s legacy in this moment?

Gary Simmons Well, first of all, so one of my dearest things about Tate was I could bump into him on the corner of Broadway and Astor because he would just hold court there. And if you walk down Broadway, you saw Tate in his Carhartt and his boots just, and his bag over his thing, and somewhere lurking, if you’re lucky, A.J. shows up.

Jeff Chang For our listeners, A. J. is Arthur Jafa, a renowned visual artist, cinematographer, and filmmaker best known for his work with Julie Dash, Solange Knowles, and Jay Z. And for his piece, Love is the Message, the Message is Death, he was a longtime friend and intellectual sparring partner of Greg Tate.

Gary Simmons If you get in a conversation with Tate and A.J. and yourself that, that conversation can take hours. I mean, dream can attest to this. I mean, it’s like hours. My wife, Ellen, she’s been with me when I bumped into the two of them on the corner. I lived around the corner from there. I still have that apartment. So every time, talk about memory, every time I come out of my apartment in New York and I go to the corner of Astor and Broadway, if she’s with me, I instantly go, this is the Tate corner like this.

This is what this is where it all happens. And for me, I used to ask him, why do you stand here and do this? And yes, his office was there. But for him, it was like life comes to you and through you and, you know, those things that he may have said, a lot of them are very poetic and accessible to many people.

Each of us had these like, intimate relationships with Tate that defined how we understand him. I think there’s also when you start to hear other people tell stories, you click into those things, and there’s a kind of unity to it. It’s like, Oh, you’re one of us. It’s almost like that movie Goodfellas, like, oh, yeah, he’s a good fellow.

You know, you name it and it passed through them Even in my studio, and that was, that’s a very special talent to be that griot and filter that people of all backgrounds and forms of production pass through. Like, it’s just, it was one of those moments in New York downtown that you had all of these incredible people, I can actually still see dream walking down from Union Square towards Astor Place and dropping in for like a minute.

You know, and seeing us like sitting there talking and just being like, you guys, man, I got to get up out of here. It’s too much testosterone here for me.

dream hampton I felt like I was Elaine in Seinfeld. I don’t know who A.J. would have been, but We had a 20-year throuple thing happening, and it was all conversations, but you know, I was, as you were speaking, Gary, I was thinking about place, and I think about this all the time.

It’s so sweet that you still have your place in New York, but no place stays the same. Nothing is static about place. And I knew, like, when I landed in New York, people were bemoaning the 80s. They were like, it’s over. You just missed Jean Michel and, you know, Fabricating his stories of, like, what the 80s were like.

And then that, when I arrive in 1990 to attend NYU, there’s a whole nother New York. And so a city like that is constantly resetting itself. So I have this sadness of, like, you know, New York without Tate is not New York to me, right? I also don’t, I’m not a nostalgic person, so I know that there’s a New York that’s happening that feels like what you were talking about, Gary, where people are still just running into each other.

They’re having their queer day parties in Brooklyn, and there, it’s just something we don’t have access to. Like, we’re not the kids anymore, so we have our memories, and we’re standing in front of a Duane Reade like, this used to be Nell’s.

Gary Simmons Haha, It’s totally true.

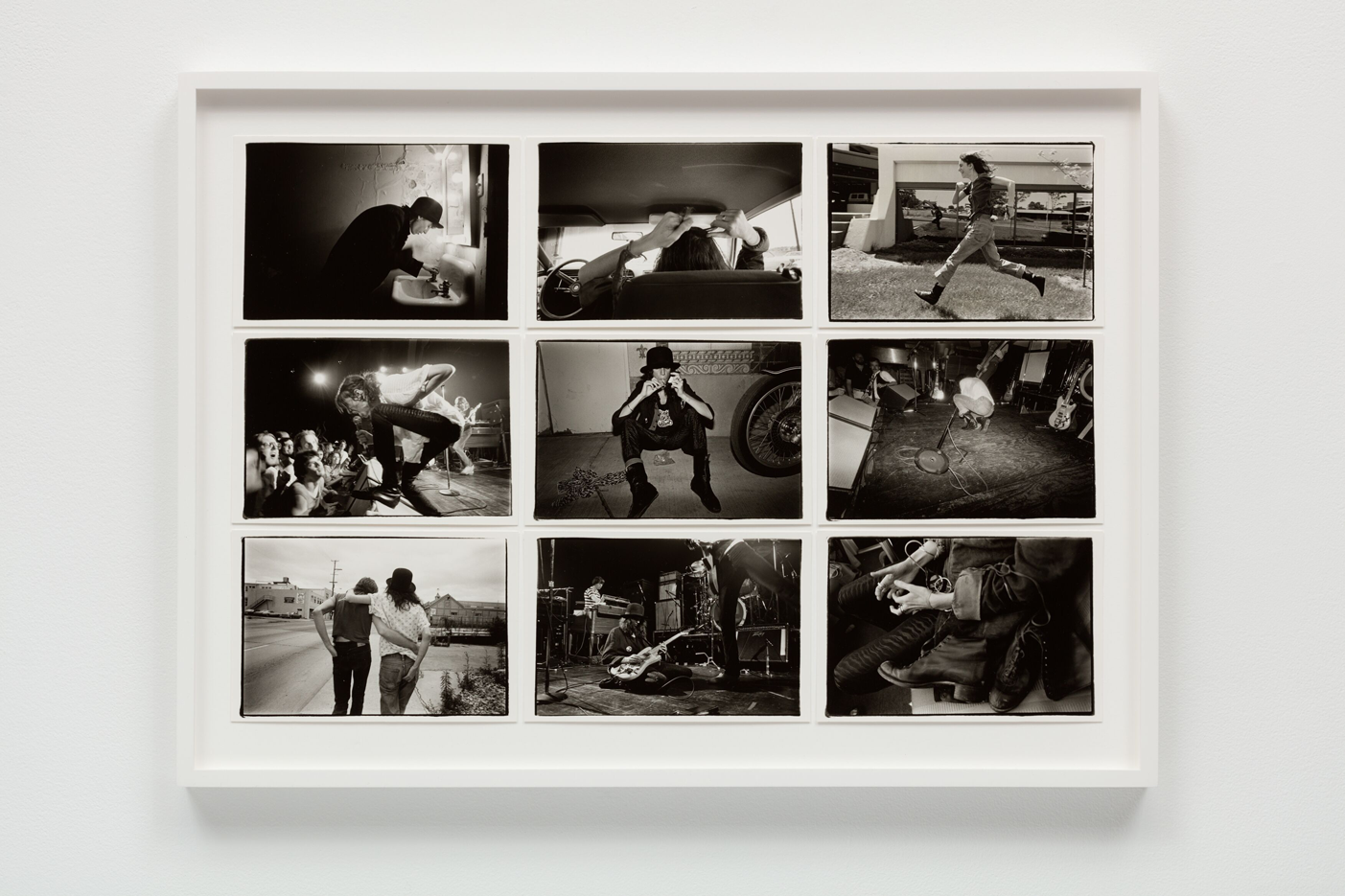

Jeff Chang dream, I wanted to bring up Gary’s backdrop photos, especially since you were the subject of, of one of them. These were scenes where Gary took portraits of friends and strangers, and they were like real-time snapshots, I guess, in a way, much like what we see on today’s social media. But over time, they’ve become a, this collection, something deeper, a self-portrait, maybe of a community in a specific moment.

How do you see artists, including yourself, activating the process of, of capturing and preserving collective memory within a community? And how does that process shape the way we, as a community, make history through shared memories? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

dream hampton I don’t know that one should be thinking about history when one is in the process of making work, you know?

I think that If you feel the work is important, and I haven’t always felt like everything I do is important. But when I am, particularly when I’m holding other people’s lives in my hands or stories in my hands, I do always take it as a serious and important work. And I’m not concerned, you know, this is this question of being present in the moment.

But you don’t have an idea what’s to come. And when I’m shooting Biggie, for my class at NYU, which is really the thing that’s in front of me. And then later for a documentary that I was calling, And It Don’t Stop. I’m shooting him for that. I have no way of knowing the fatal standoff that’s gonna cost him his life, the some rat beef.

I have no way of knowing what lies ahead for all of us. It’s important to just be present in that moment and to be I don’t even want to use words like honest, you know, um, because maybe honesty isn’t always the assignment, but an authenticity definitely isn’t always the assignment, you know, so it doesn’t always have to be literal.

Um, it doesn’t even always have to be honest. You know, I love a good yarn, a good tail. And I think about that with family members who spend these yarns for us, right? Like that. Okay. You know, that is just as important. That becomes its own kind of truth. It’s the lies you tell to survive something, to, you know, to spruce it up, to spice it up.

But either way, the idea of history shouldn’t be at our forefront as we’re creating.

Jeff Chang dream, you were speaking about the importance of being present as an artist in the moment when you’re creating, not thinking necessarily about what the impact is gonna be down the line, uh, about making history, so to speak.

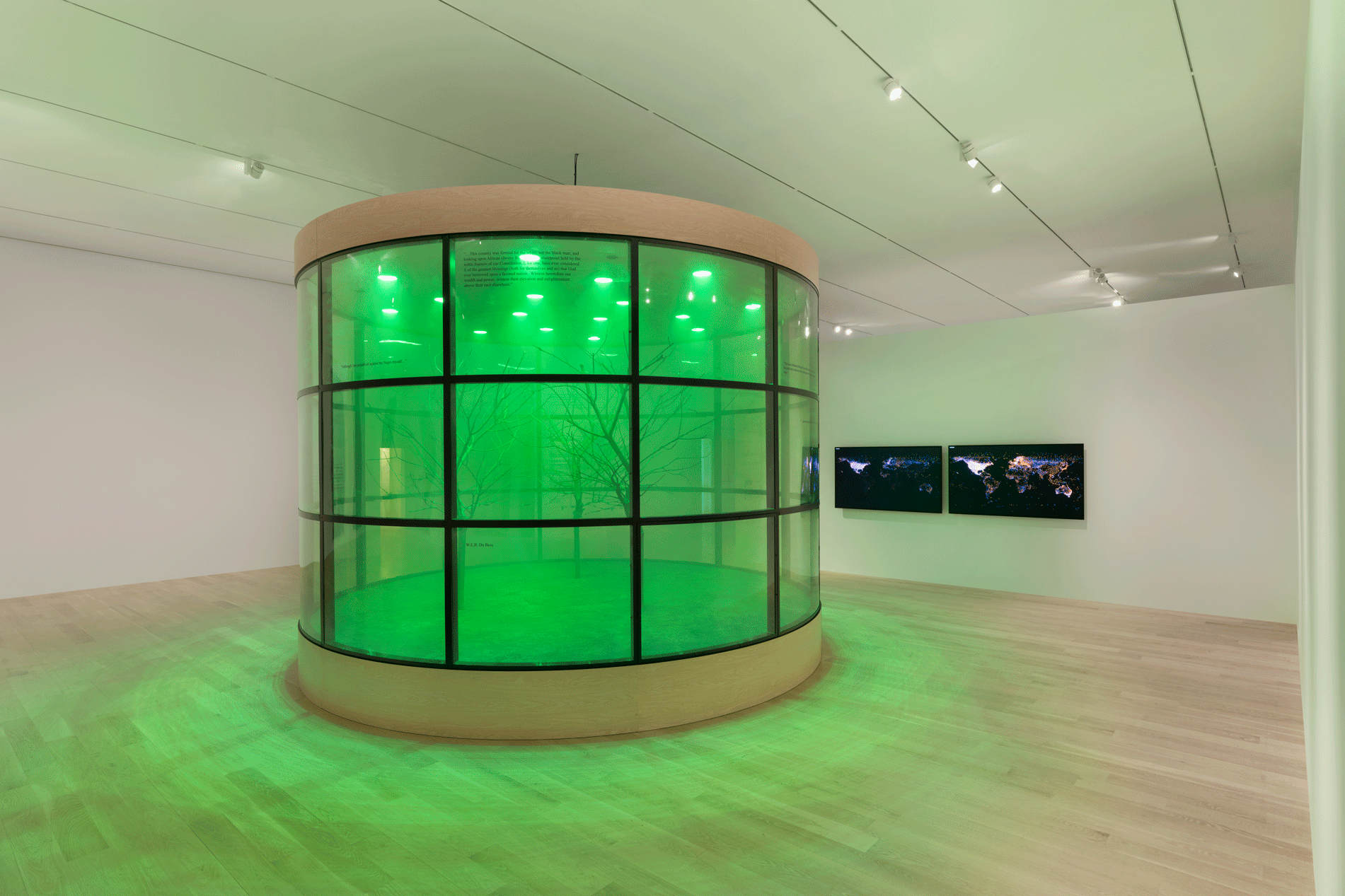

And I’m thinking about the ways that that kind of immediacy also connects up with Gary’s work. Gary, could you talk about your Black Ark installation and how that captures memory and history, especially in the context of creating something in the moment that later takes on a deeper kind of historical meaning?

Gary Simmons That’s interesting. I think something like the Ark taps into some of the things that dream was just talking about. That’s a very personal piece in some ways for me that I leave out of the equation or out of the way it’s talked about or defined. Generally, you know, music was very important in my household, and my father had a really quick fuse temper, and it could get scary sometimes, and uh, one of the ways that we chilled it out was with music.

So if I got myself into some problems I’d look at my sister, and she’d be, like, scrambling around for Johnny Nash records.

I think about why that piece was called Recapturing Memories of the Black Ark was, it’s based on Lee Scratch Perry’s studio, which goes to memory to begin with. He burned down his studio, I think, two or three times, and that was called The Black Ark. So, I always loved the way the Jamaican sound system worked as this center in a community, this booming sound, and I thought, I want to take some of what was left behind from Katrina.

I was invited to do this show in New Orleans, so I drove around the Ninth Ward, collected a lot of wood, and got together with a carpenter who was also a musician. And I said, listen, I want to make a Jamaican sound system out of all of this. This discarded wood, this terror, really, of these destroyed houses and lives.

It’s terrible, really. The thought of destroyed houses and lives. I thought it would be great to, to put something together that was positive. And what completes the piece is, I invite other artists to come and perform on the Ark. So once it gets turned on, by whoever, we record it via video, and it’s, it’s put into a kind of library that just keeps going, but it’s, it’s fantastic to watch how people see this object interact and mesh into different cultures. It’s fantastic.

It’s, to me, that’s how memories formed is almost collectively to put a, you know, a cherry on this.

Jeff Chang Well, it’s been incredible to share memories with both of you today. Your insights and stories have given us so much to reflect on, from the personal to the collective, and how memory continues to shape our art, our communities, and our histories.

Thank you both for allowing us to listen in and explore these powerful connections together—here on Edge of Reason.

<< Outro music >>

Jeff Chang Well, it’s been incredible to share memories with both of you today. Anytime I can get with either one of you is amazing. But both of you together at the same time. Wow. Thank you both for joining us on Edge of Reason.

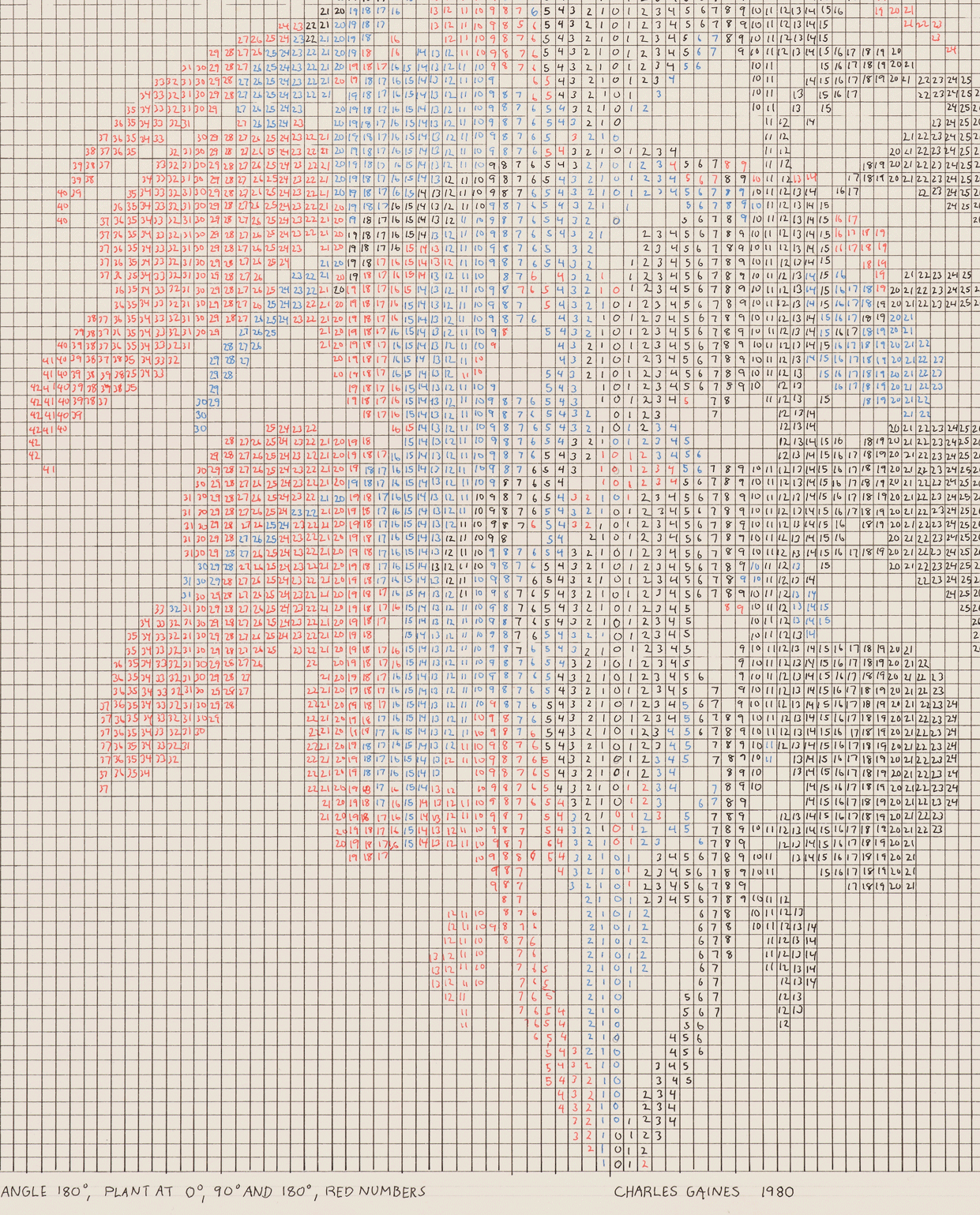

I’m Jeff Chang, and you’ve been on a journey to the Edge of Reason. Join us next week when we speak to Hauser Wirth artist Charles Gaines and acclaimed fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner to explore how perception versus truth drives their work.

If you enjoyed what you’ve just heard, Like and review on Apple Podcast, and help spread the word about our series to other listeners like you.

GALLERY

to see more

Our Voices

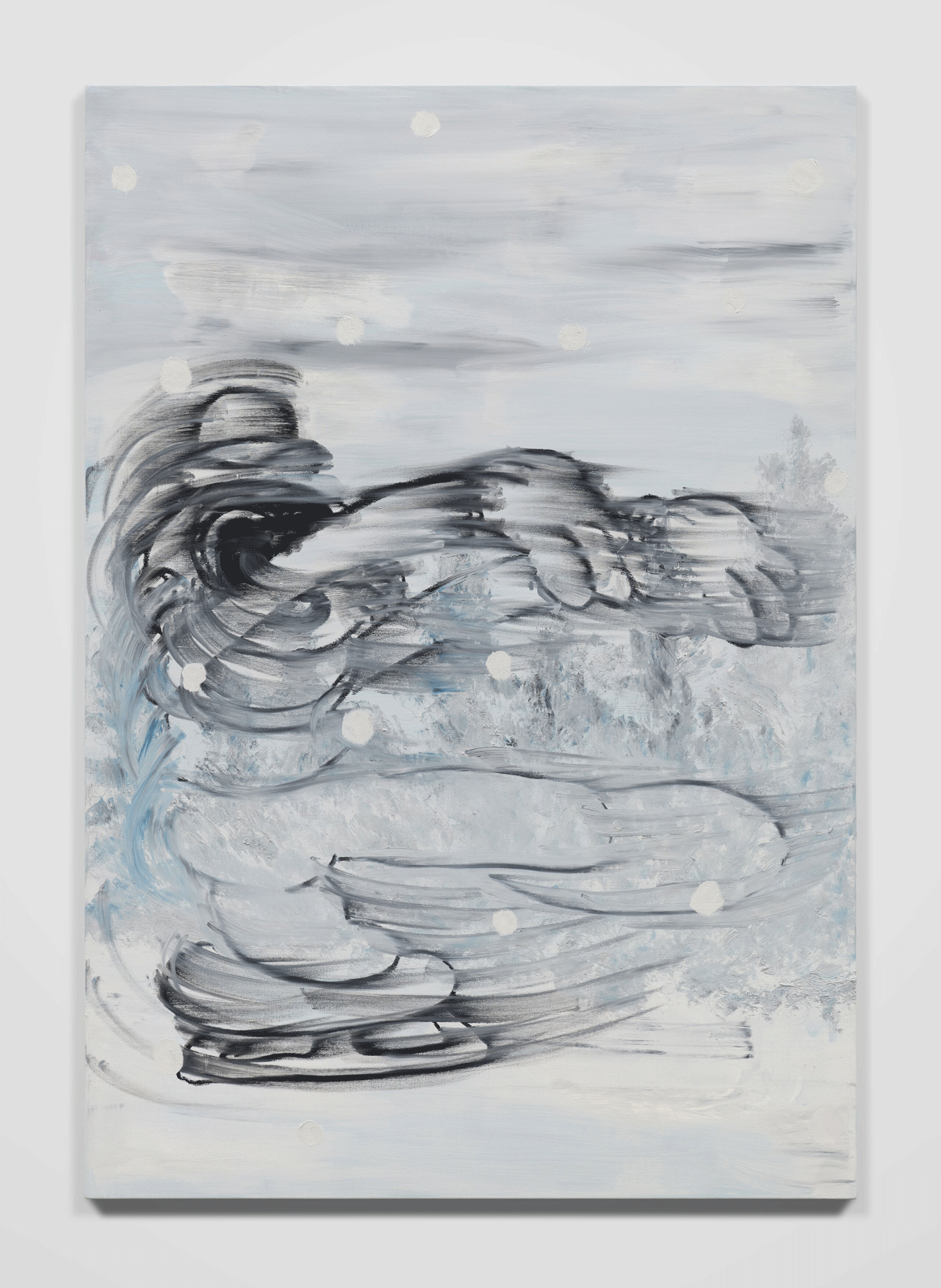

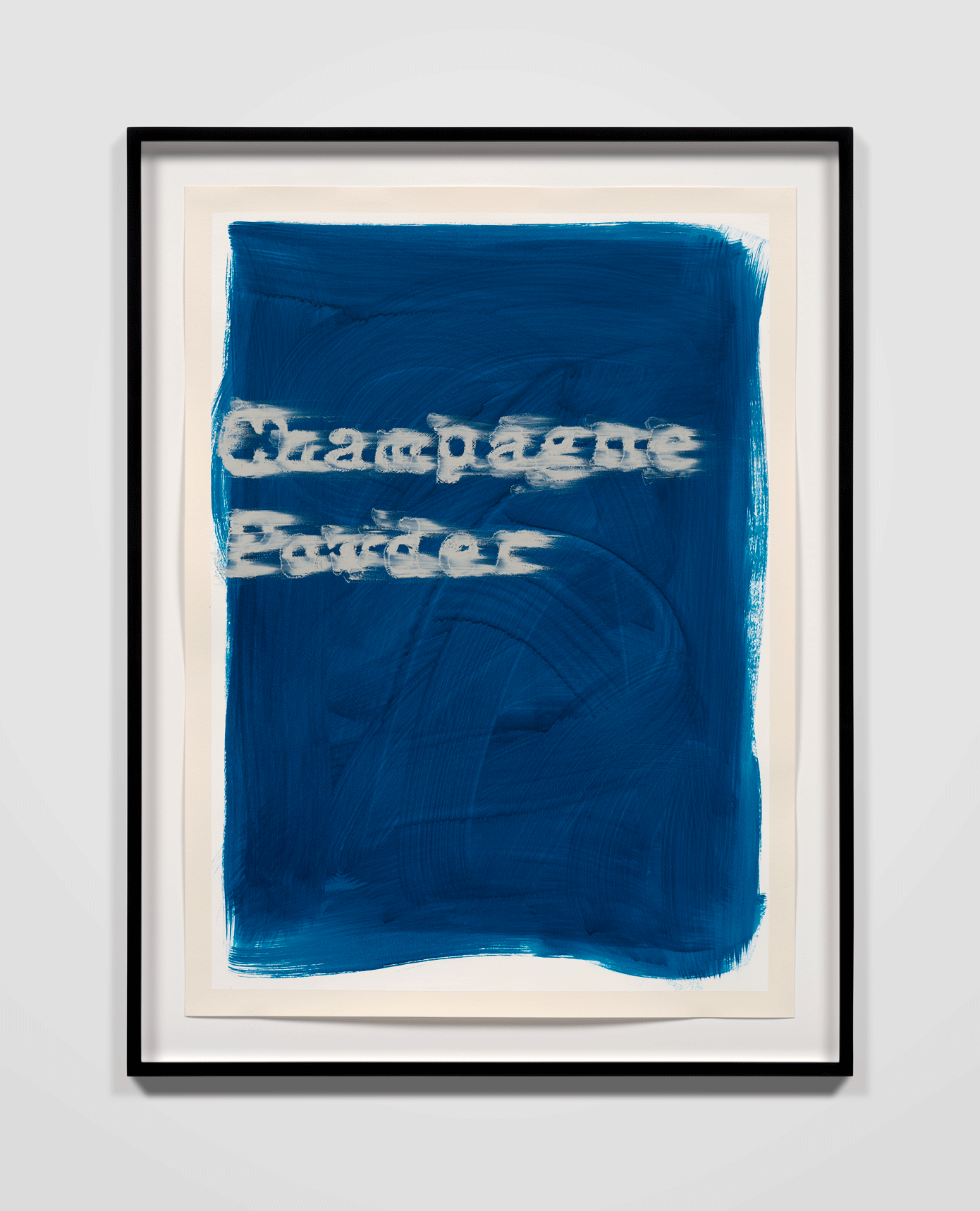

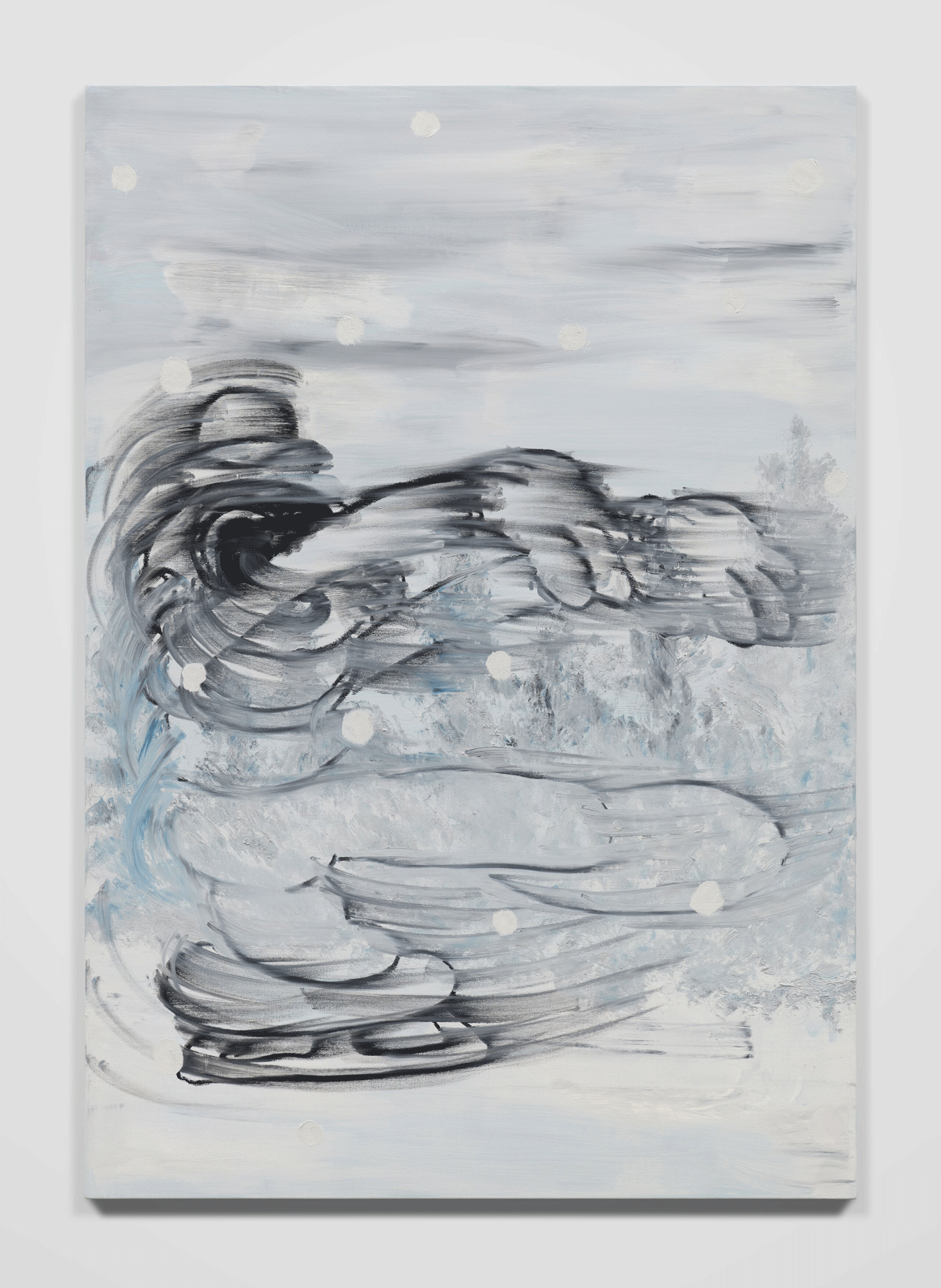

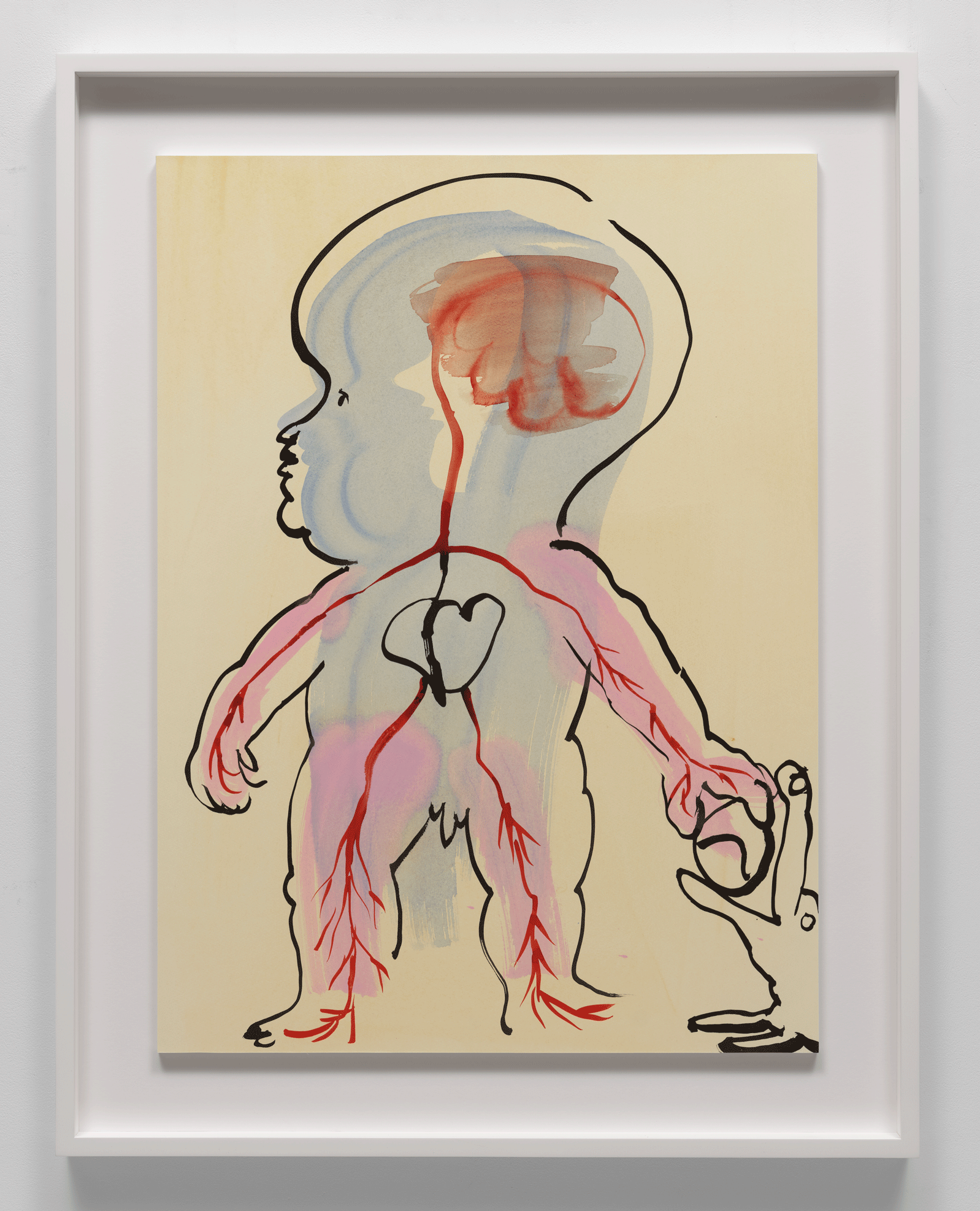

Gary Simmons is an acclaimed artist known for his signature “erasure” technique, blurring imagery to explore themes of race, memory, and cultural history. His multidisciplinary practice spans painting, sculpture, and installation, revealing the hidden narratives and collective memories embedded in popular imagery. Through his work, Simmons challenges viewers to reconsider how memory is constructed and how it shapes our understanding of the past and present.

dream hampton is an award-winning filmmaker, writer, and activist whose work centers on issues of race, gender, and justice. Perhaps best known for her groundbreaking documentary Surviving R. Kelly, which earned her a Peabody Award, hampton has spent decades amplifying underrepresented voices and uncovering silenced stories. Her influential career spans journalism, film, and activism, positioning her as a leading figure in the exploration of cultural memory, identity, and truth.

with

Grace Wales Bonner

Listen Now →

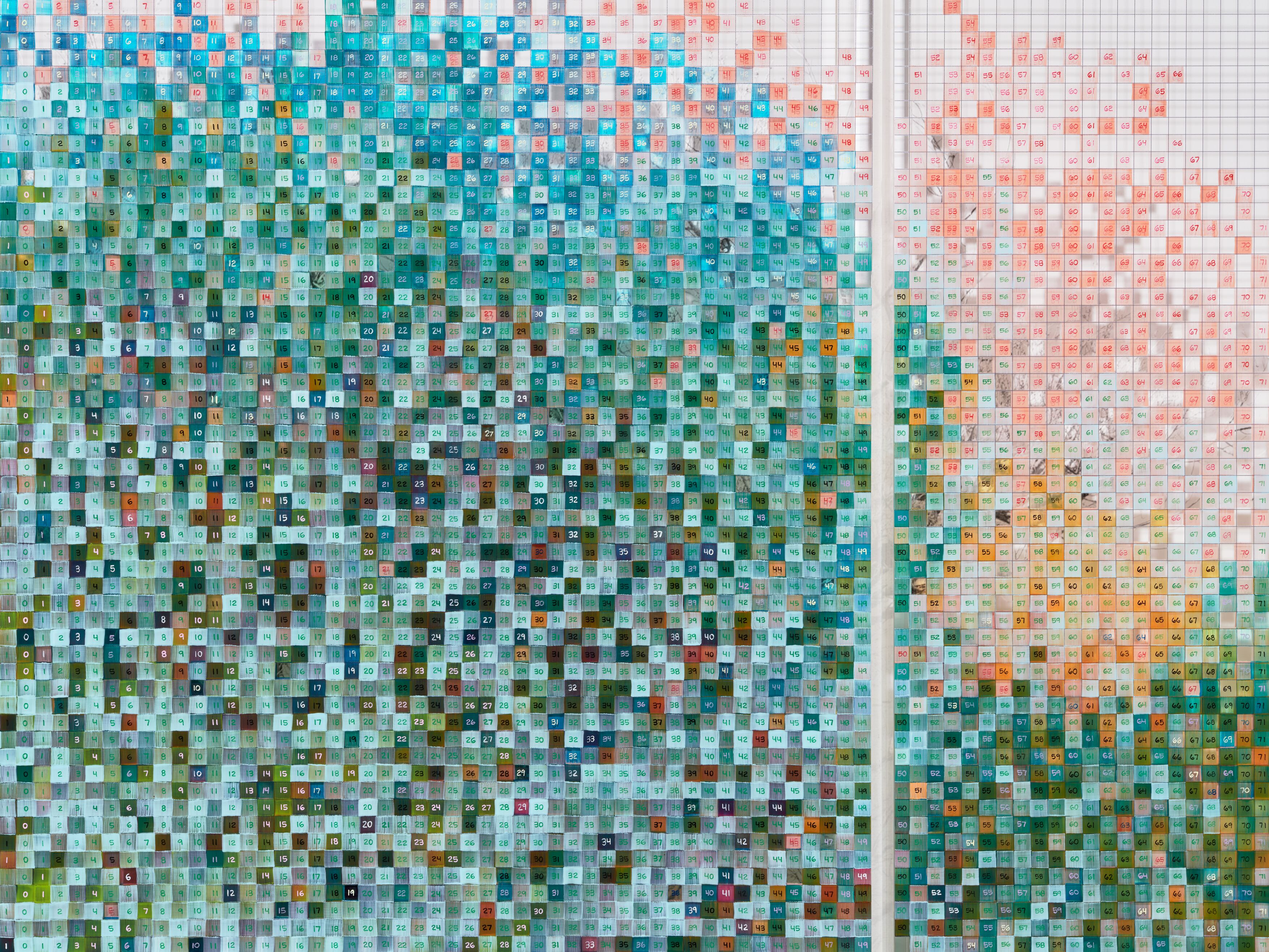

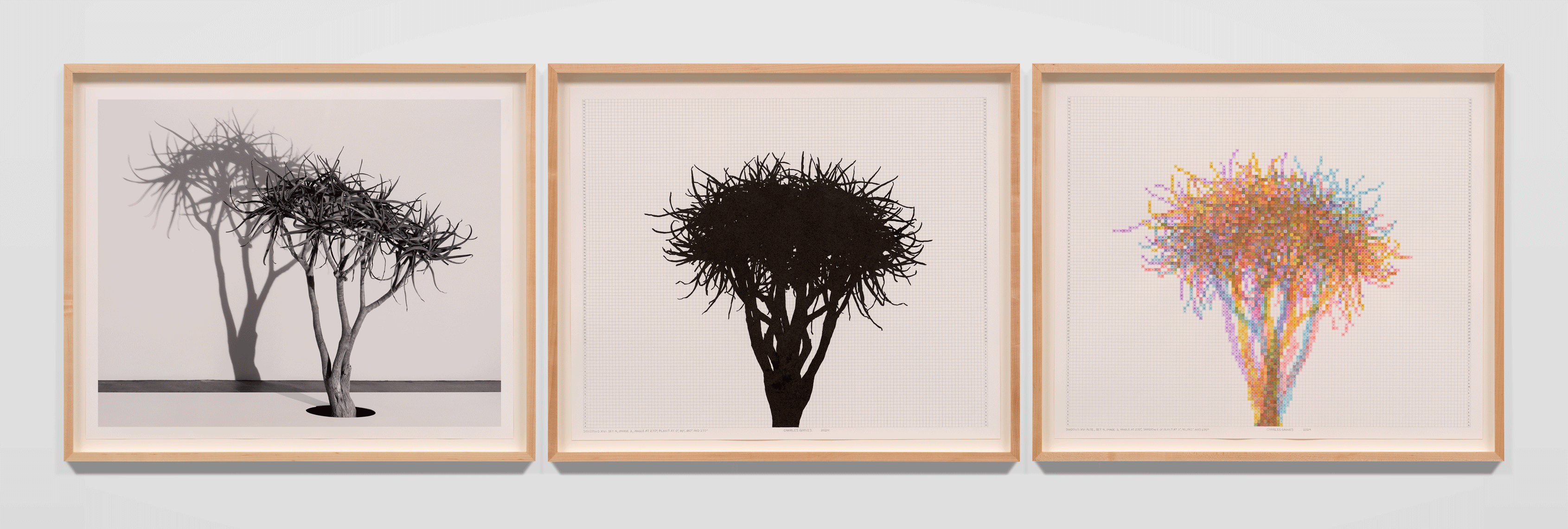

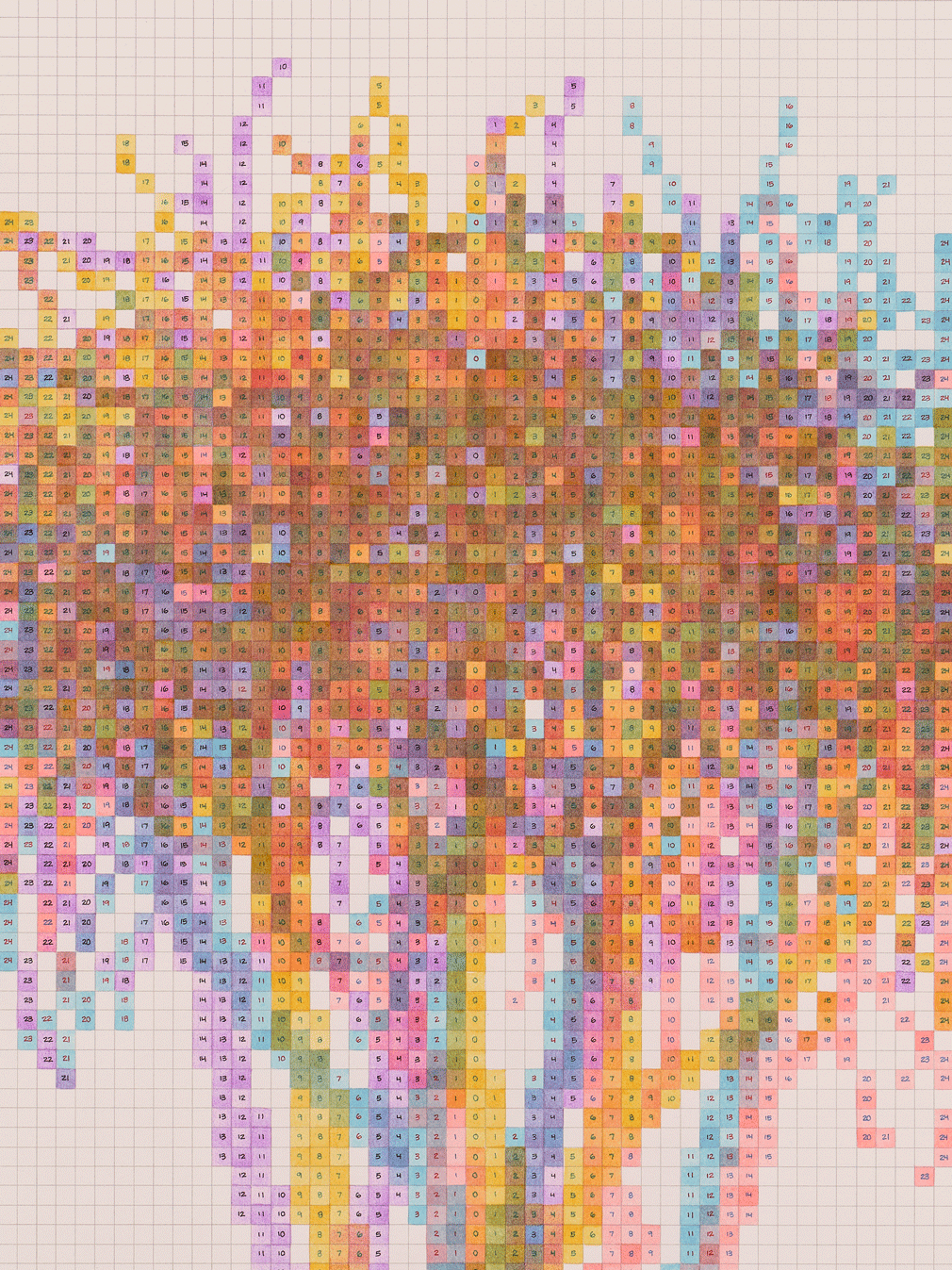

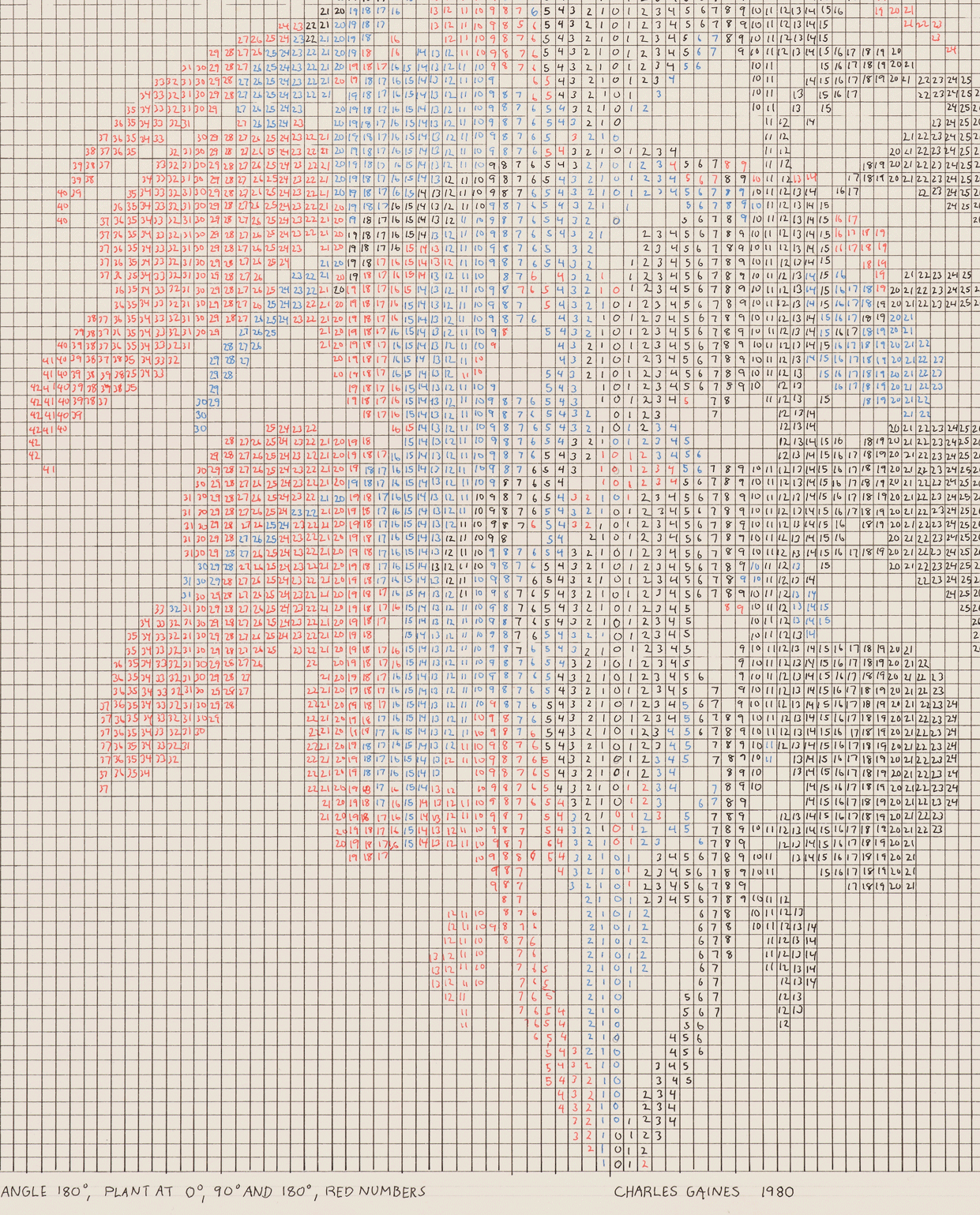

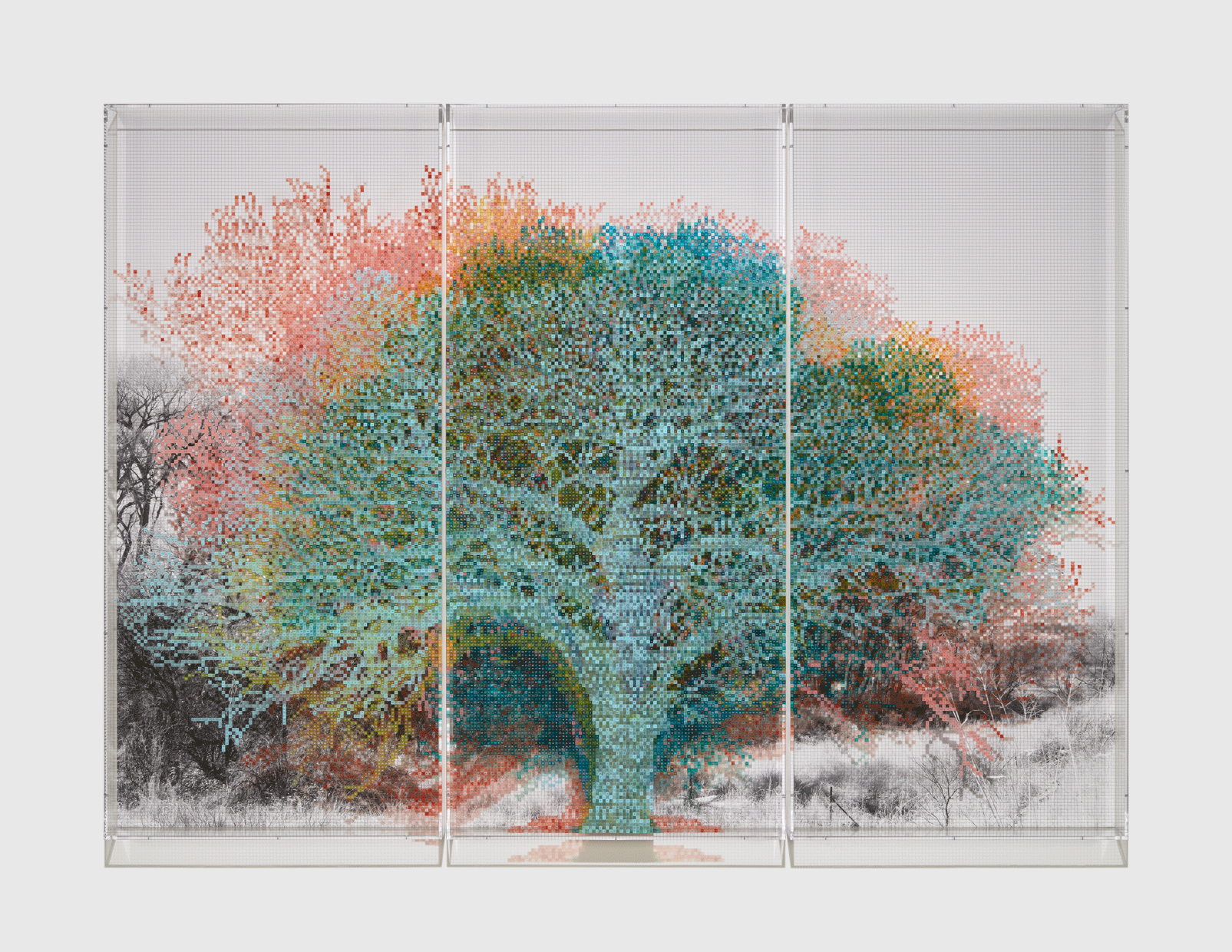

Charles Gaines

with Grace Wales Bonner

PERCEPTION VS. TRUTH explores how subjective interpretation and objective reality intersect, challenging us to question the blurred lines between what we see and what is real.

In this episode, artist Charles Gaines and designer Grace Wales Bonner delve into the ways in which subjective interpretation and objective reality shape our understanding of the world. Gaines’ conceptual systems challenge the notion of a singular truth, while Bonner’s fashion designs reveal the layers of identity and history embedded in her work. Together, they reflect on how art can bridge the gap between what we perceive and what is real, prompting us to question and deepen our relationship with truth.

Edge of Reason, Season 2 | Perception

SECTION ONE | THE THEME

Jeff Chang: In a world where the lines between image and reality, between perception and truth are increasingly blurred, understanding reality feels more complex than ever. For centuries, artists and thinkers have pursued this question: how can we represent the world in ways that get people to think and to feel? Today, we’ll explore the idea of “Perception” and “Truth.” A theme that challenges us to examine the ways in which artists reflect and reveal society. How do artists move their audiences to perceive the world and experience truth? How do they mold how we think and how we feel through the paintings, the music, even the clothing they make? Is a common shared truth even attainable? These are some of the questions we will encounter at the… Edge of Reason…

<< Theme Music >>

Jeff Chang: …a limited-series podcast produced by Atlantic Re:think—The Atlantic’s creative marketing studio—in partnership with Hauser & Wirth—a home to visionary modern and contemporary artists. This season, we explore the line where left brain meets right brain; where logic and reason end and creativity begins; and how personal and universally resonant themes—like “Perception” and “Truth”—connect art with the human experience.

Joining us on this episode are two visionary artists who embody this exploration. A pioneer in conceptual art, Charles Gaines uses systems and algorithms to challenge how we perceive reality. Grace Wales Bonner, an acclaimed fashion designer and visual artist, blends Afro-Atlantic aesthetics with European tailoring traditions, crafting garments that tell deeper stories about identity, race, and culture.

Together, they offer profound insights into how art can bridge the gap between perception and truth, leading us to a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

SECTION TWO | THE ARTIST

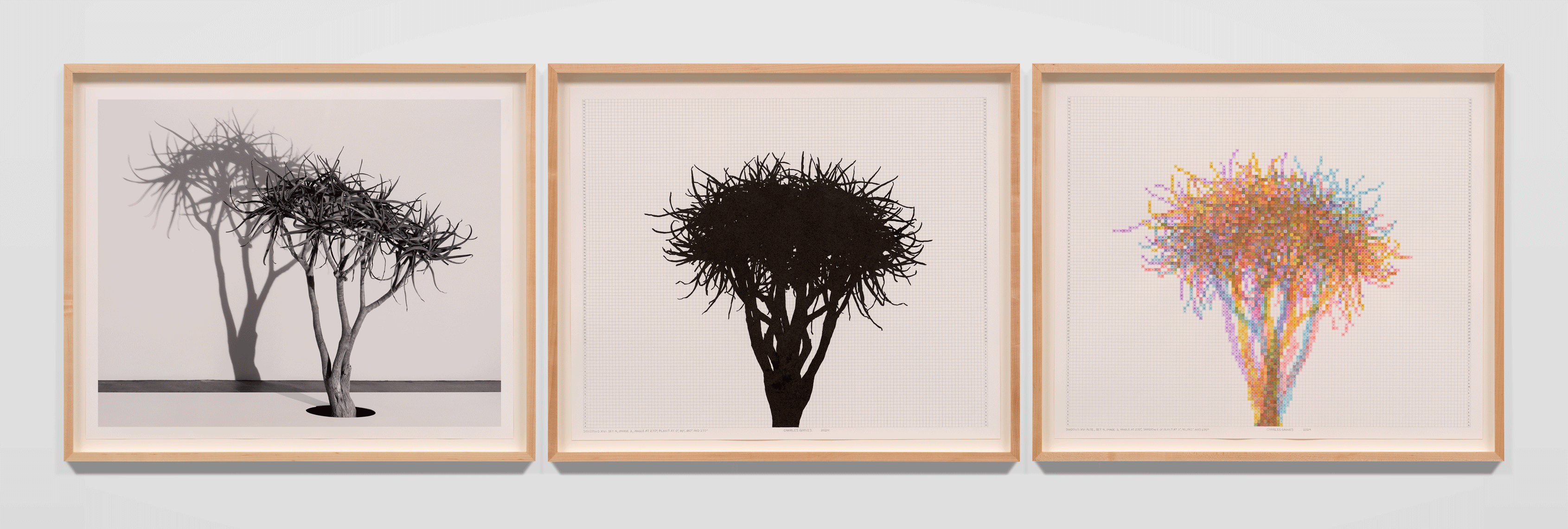

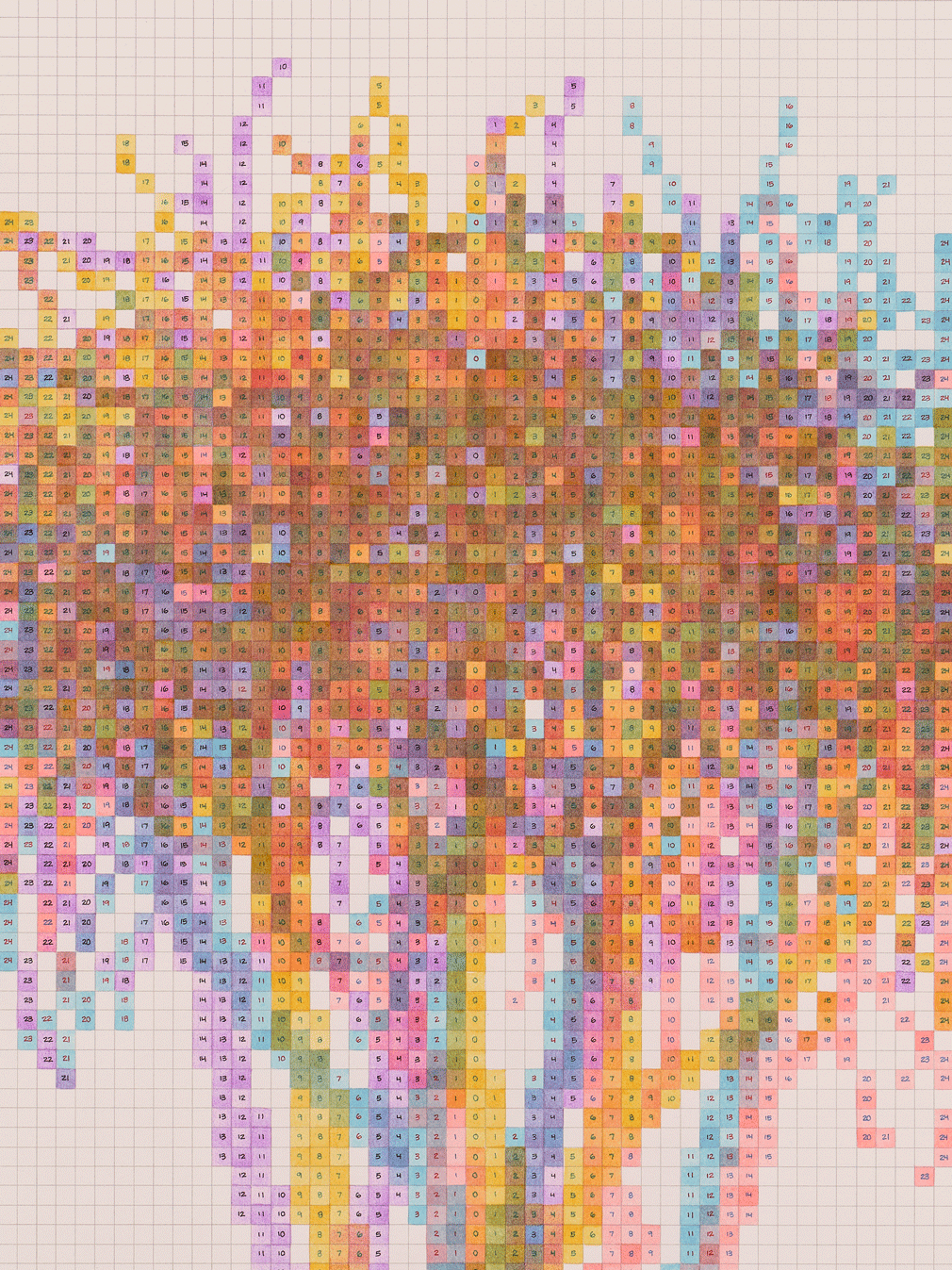

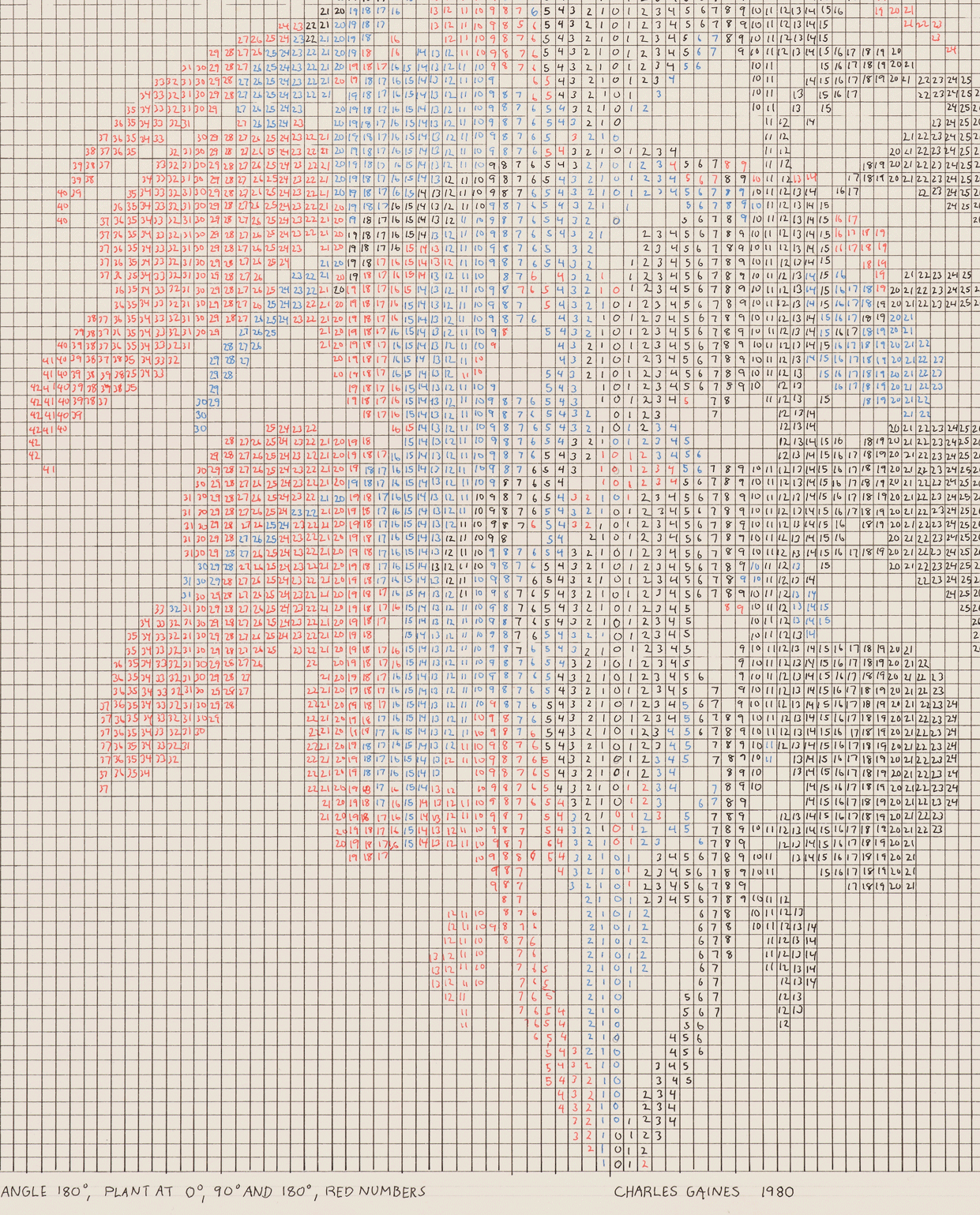

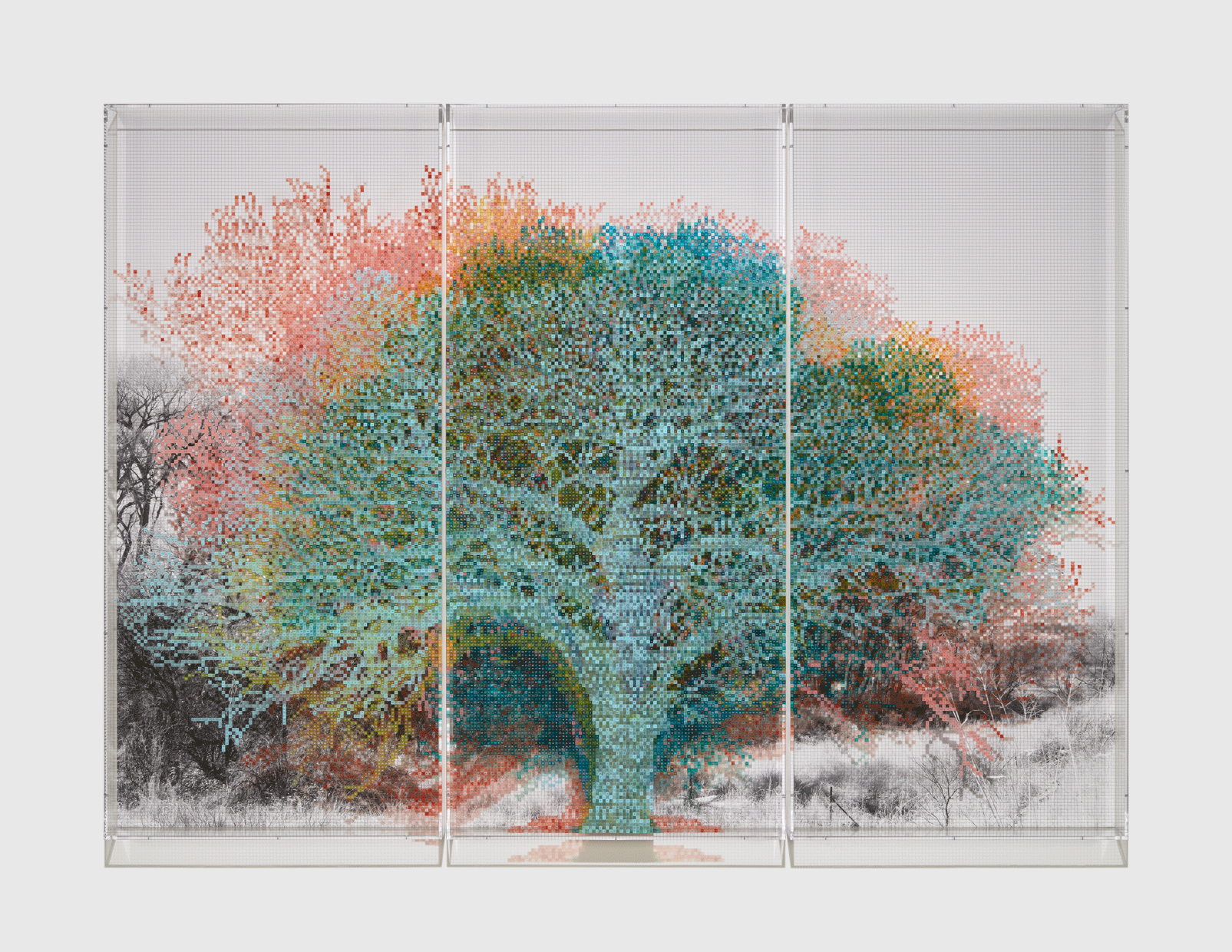

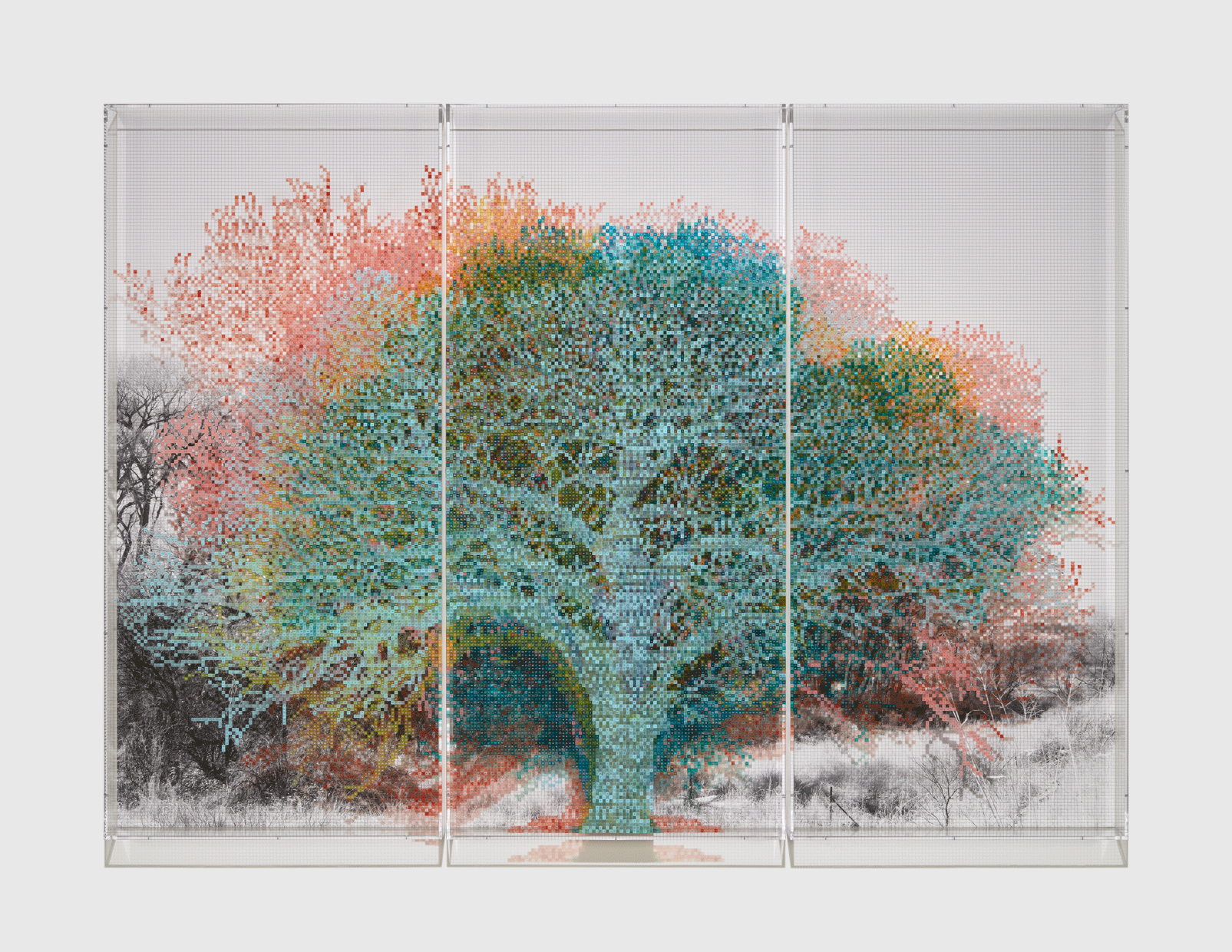

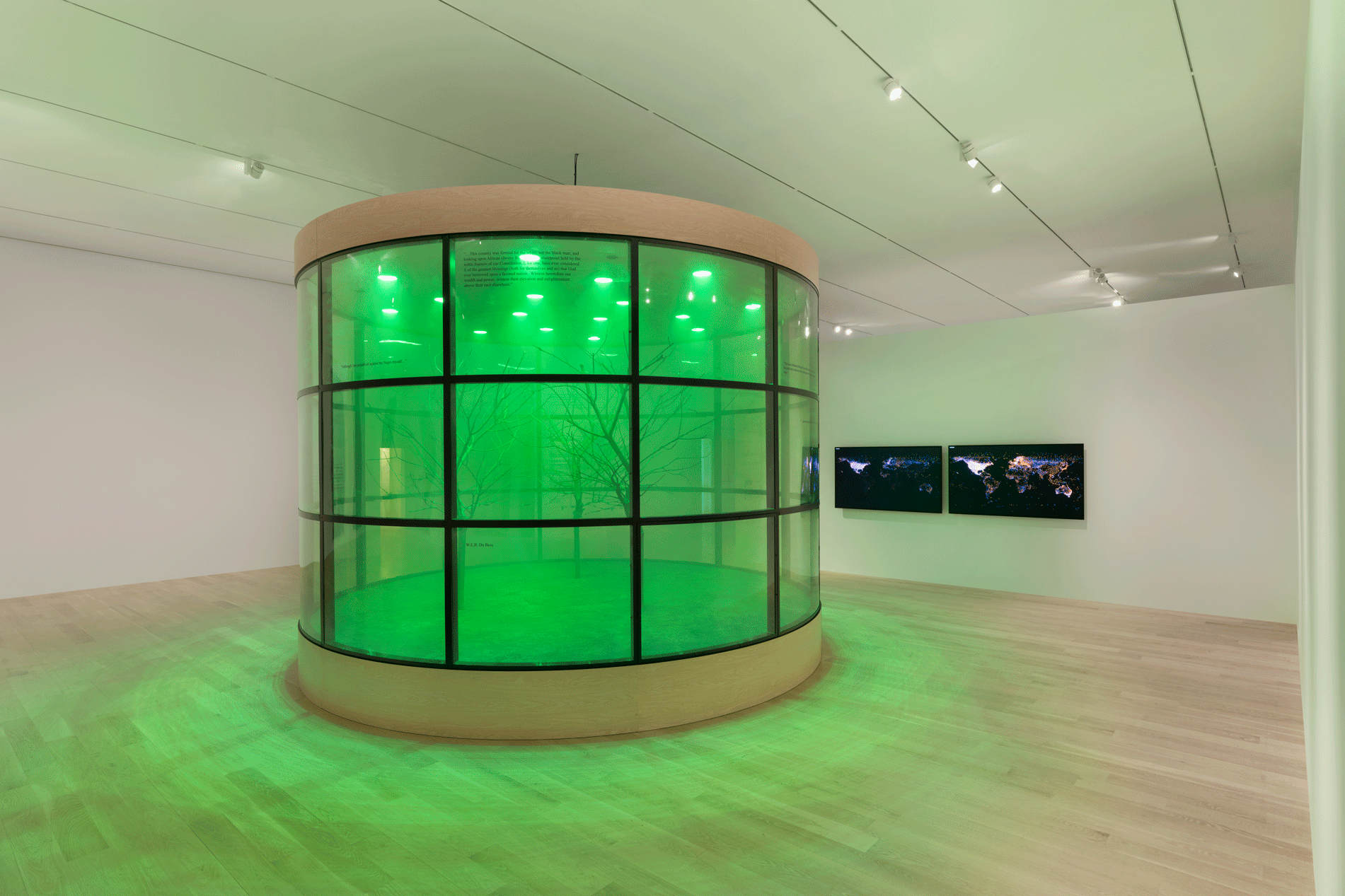

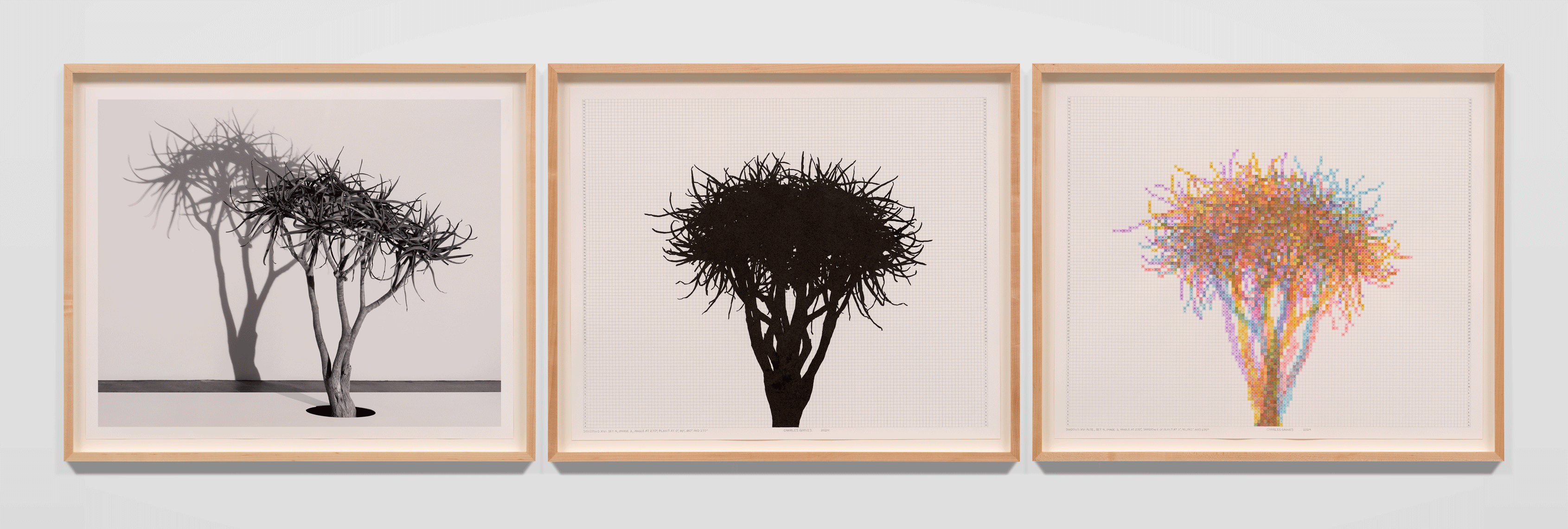

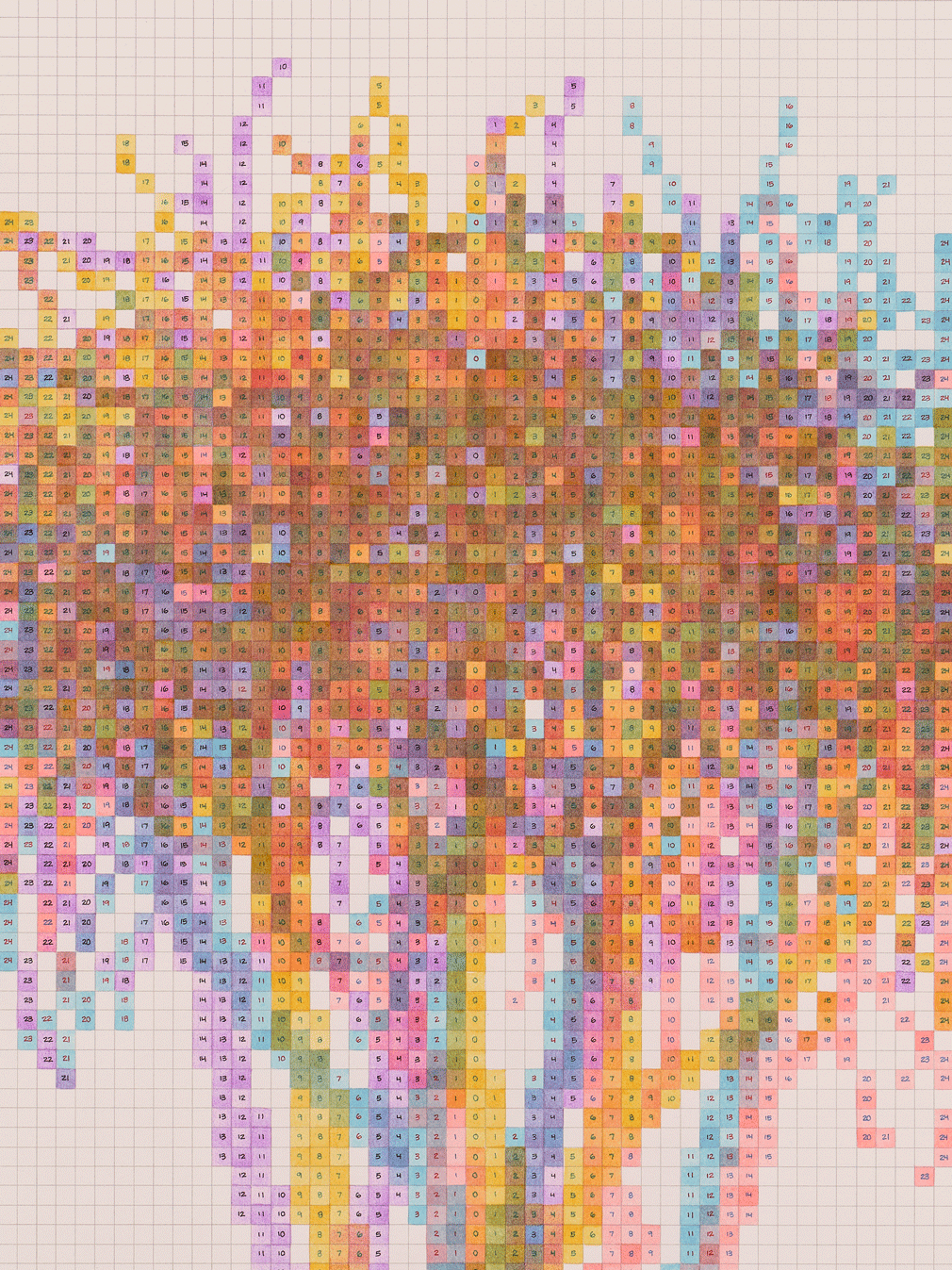

Jeff Chang: At 80 years old, Charles Gaines has had a long, storied, and multi-hyphenate career. He has made paintings of palm trees, the faces of multiracial people, and other objects that layer images upon images upon grids, as a way of showing us how we make order of points of data. But he is also an accomplished composer and drummer. His work challenges us to think about how we individually and collectively create truth and beauty.

Charles, welcome to Edge of Reason.

Charles Gaines: Thank you for having me.

Jeff Chang: I wanted to start with a question, actually, about growing up in the 1950s in the Black neighborhoods of Newark. You excelled at art and at music but some of your teachers, underestimated you. And I’m wondering, how did this shape the artist that you became and the way that you chose to make your art?

Charles Gaines: I was born in Charleston, South Carolina, and moved to Newark when I was five years old with my family. And we moved into a neighborhood that was almost all black.

But it was a neighborhood in transition. There was a high school called Arts High School that you can say was the first, high school dedicated to to music and art.

I got a really good education, but I had this feeling of being overlooked, which I understood later, to be a general feeling that black people have in a area or a neighborhood that they aren’t dominant.

And one of the things that was with me from a very young age is a certain curiosity about the way things come to be. A certain interest in the values and meanings of the social and cultural situation around me.

Obviously, the the most important of those questions was: Why am I black and why is there racism? Why are white people privileged and black people aren’t?

And I think that they, reflecting back on the past, they got me to, to believe that my general interest in the critical assessment—social-political assessment about my environment— was something that came out of that experience of: first, Jim Crow laws in the South and then the, kind of, de facto segregation that happened in the North.

And I read what those things meant, and it didn’t make sense to me. I thought it was completely unjust and unfair. And I wondered about how those things got put into place.

Jeff Chang: Mmm. I want to come back and ask you a lot more questions about how that drove you into conceptual art as opposed to other types of forms that your work might have taken.

But let’s bring in our guest right now, Grace Wales Bonner…

As one of the most exciting young fashion designers in the world, Grace makes some of the most beautiful and desired clothes in fashion, which reveal an attention not just to detail and fit, but also to the storied history of Black art and artmaking.

The details are often subtle— a monogram here, a stitching there, a detail from a Kerry James Marshall painting or an image by Sanlé Sory or an inspiration from a poem by Ben Okri.

Grace, welcome to Edge of Reason.

SECTION THREE | THE EXPERT

Grace Wales Bonner: Thank you so much for having me. It’s a pleasure.

Jeff Chang: Grace, I’m wondering, you know you grew up in in London in the 2010s—a much different time, a much different place. And as you’re listening to Charles’ story, I’m wondering how you reflect upon your own personal experiences and how that shaped your particular approach to making fashion and art that live in the world.

Grace Wales Bonner: Yeah, it was interesting hearing Charles and those were definitely things that I could relate to in what he was saying in terms of certain questions around identity and also thinking about systems and structures that can support or hinder expression.

So I grew up in London, and it’s quite a multicultural city. So I think that informs the way I think about culture and cultural expression. And, kind of, questioning also having a white mother and a black Jamaican father. I guess I was thinking a lot about representation, as well. But I think at a formative age then I started to, kind of, think about, for example, being Black doesn’t need to be fixed in any way.

I think my work has been very guided by showing a sense of its expansiveness and possibility. And I think I’ve also been gravitated towards expressions of beauty and elegance, which I guess I’ve probably grown up around. When I think about representation, a lot of what I think I do now is about connecting with history, connecting with a living archive and revealing threads that have always been there, really.

My work very much interacts with the past, but it’s looking to create a future reality. And I think that something that guides me is an exploration of beauty. And if I think about what I did growing up, I was seeking images. I was seeking images to confirm a sense of identity and belonging.

Even if if I was somehow dislocated, say, from family in in Jamaica, I think I used images as a way to connect to people.

Jeff Chang: The two of you recently connected to collaborate recently on Grace’s Spirit Movers exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. And yet you all, the two of you haven’t had a chance to really sit down and and talk. So it’s an honor for us to be able to be here and listen in on this conversation.