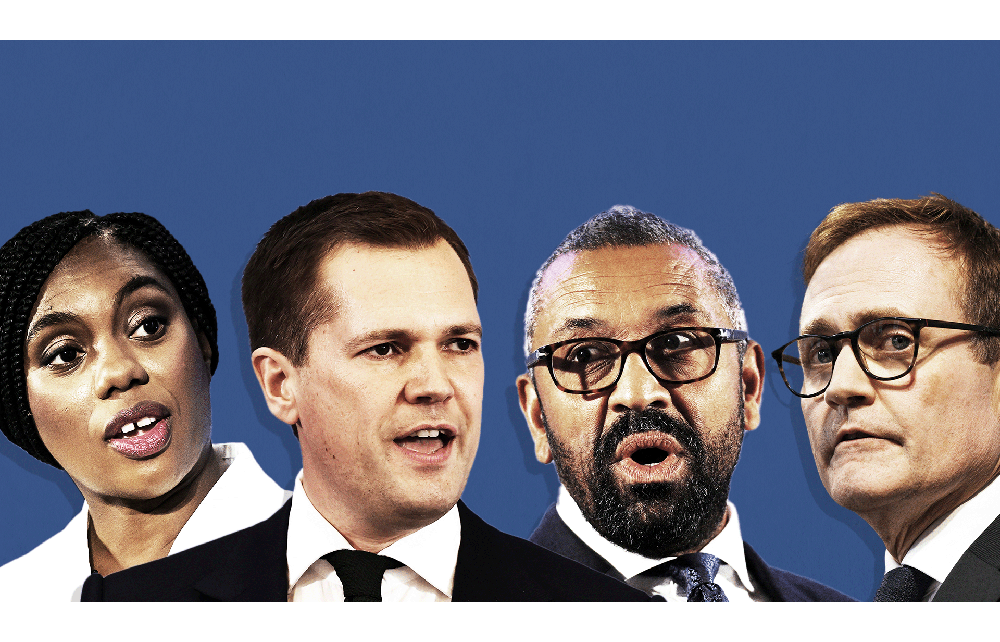

As the four candidates prepare to make their pitch at the Conservative party conference in Birmingham, we quizzed them about their ideas and ambitions.

Why did the Tories lose the general election?

JAMES CLEVERLY: We lost the ear of the British public. They stopped listening to us. We over-promised and under–delivered on a load of issues so our election promises were met with real cynicism. People had literally closed their ears – and minds – to our arguments. Even if we had had the best policy platform in the world, people weren’t willing to give us the time of day. If we make fewer promises but make sure that we deliver on all of those promises, we will regain trust. But that means being disciplined.

ROBERT JENRICK: The government didn’t address properly, in a truly Conservative way, the big issues. We made promises and didn’t keep them. We lacked the courage to do the things that were necessary and which the public would expect of Conservatives, like reforming the NHS, or delivering proper supply-side reforms to get out of this cycle of low economic growth, poor productivity growth that we face as a country (and have done for years). Failure to address immigration and to heed the warnings that I gave at the turn of the year. That was the real reason.

KEMI BADENOCH: When I was campaigning, I’d knock on one door and the person there would say: ‘You’re too left wing.’ And I’d knock on their next-door neighbour’s door. ‘You’re too right wing.’ A few doors down, somebody would say: ‘You’re too centrist.’ The bottom line was people didn’t really understand what we stood for. They just thought we were telling them whatever it was they wanted to hear. And I think to some extent, that was true. We were not leading. We were following. Having focus groups asking people ‘What is it that you want?’ and then trying to offer them that is not true politics. It’s the Henry Ford problem. Henry Ford said that if he’d asked people what they wanted, they would have asked for a faster horse rather than a car. Real politics and real leadership is about showing the way and getting other people to follow you, not just asking them what it is they want and trying to split the difference. That is where managerialism creeps in.

TOM TUGENDHAT: Well, there are many reasons but the fundamental one is we lost the trust of the British people. Let’s be absolutely clear, a lot of people chose to vote either Reform or Lib Dem or Green or in a few cases Labour because they had simply stopped trusting us. They’d seen us arguing among ourselves, they didn’t know who to believe, who to listen to and they went: ‘Well if you can’t agree, then there’s no way I’m choosing you.’

Does the UK need to leave the ECHR to control immigration?

JENRICK: Reform [of the ECHR] doesn’t exist [as an option]. It’s a binary choice: you either leave or you remain. We should leave. There are those who say that we should attempt to derogate: that’s impossible. So I think we all face a simple choice: ‘Do you want to remain within it?’ If so, you’re consigning this country to illegal migration for decades to come with all the consequences that flow from that. Or you can leave, fix these problems once and for all and then settle the migration challenge that we’ve faced as a country. Then move on to talk about the other things that we care about in British politics: education, the environment, the health service, the economy. That’s where I am. I think that’s where the membership of the Conservative party is and I think that’s what we can persuade the country is the right way forward for us all.

BADENOCH: Other candidates have talked about leaving the ECHR on day one. I actually think we need to be far more radical. We need a root-and-branch reform of immigration. Countries who are in the ECHR, like Spain, for example, are able to deport illegal immigrants properly – in a way that we can’t do here. We have people in our Home Office who man our borders who don’t really want to deport, they want to look after refugees. So dealing with the people, having a strategy for what kind of people we want coming into our country is absolutely key. Then you can have a cap. Then you can talk about maybe leaving the ECHR if it’s not working, but starting with leaving just shows that we haven’t learned the lessons of Brexit – or even net zero – where we say we’re going to do this thing without working out the consequences, without working out what it entails.

TUGENDHAT: It’s not necessary to leave the ECHR to tackle small boats. What it is necessary to do is to be absolutely committed to the security of the British people and that’s why I set out actually something I have been setting out since 2013. I first wrote on the ECHR in 2013 just after I’d left the army – before I was even a parliamentary candidate. [I said] the ECHR doesn’t always work in the way that it should. Other countries have responded to this by opting out of certain elements. That’s called derogation.

CLEVERLY: Look at the United States, which has a very activist legal system. They are not members of the ECHR and yet they really struggle with deportations and returns. There are no silver bullet solutions to this – and anyone who is promising a silver bullet solution I think is slipping into the habit that we got into in the last parliament: making big bold promises that are not that easy to deliver. That’s what got us in trouble in the first place so let’s not do that again.

What’s the least conservative policy of the past 14 years?

TUGENDHAT: Vaccine passports. That’s why I voted against it.

CLEVERLY: I suppose all of us have got to recognise that our response to Covid was inherently interventionist… the social restrictions that we introduced, I think all of us now look back and say that was far, far, far too much. It was the Conservative party and we cancelled Christmas. I mean Boris Johnson and Oliver Cromwell, the two national leaders who in our history cancelled Christmas and you wouldn’t have expected the Venn diagram of Oliver Cromwell and Boris Johnson to have had much of a crossover.

JENRICK: I think it was failing to tackle the Blairite inheritance that we got. Just as Tony Blair accepted the Thatcherite consensus in some respects, we, wrongly, accepted what he left us: the legacy of laws that he put in place like the Human Rights Act, the Equalities Act, the Climate Change Act. These are laws that make it immensely difficult for ministers to get on and do the job.

BADENOCH: There’s so many things which I disagreed with. But the least conservative one? The smoking ban. I voted against it. I think it was violating multiple principles – personal responsibility, it violated equality under the law. It treated people who might have been born days apart differently.

Has Elon Musk been a good thing for freedom of speech?

BADENOCH: I think Elon Musk has been a fantastic thing for freedom of speech. I will hold my hand up and say, I’m a huge fan of Elon Musk. I look at Twitter before he took over and after: there is a lot more free speech. Yes, there are many, many more things that I see on, well, X, as he calls it, that I don’t like. But I also know that views are not suppressed the way that they were. That there was a cultural establishment – that was very left – that controlled quite a lot of discourse on that platform.

TUGENDHAT: We’re seeing lies grow in the darkness. We’re seeing some states exploit the anonymity of the online world to spread frank untruths that – were they able to be challenged, as you’d be challenging me and the way we challenge each other in open forum – they wouldn’t happen. So there’s an honesty element here as well. If you are running a platform that is entirely dominated by anonymous bots, is that freedom of speech – or just propaganda? If you are allowed to say whatever you like but you put your name to it, that’s freedom of speech. And it should be defended, absolutely.

CLEVERLY: Elon Musk bought what was then Twitter and set about changing it because his perception was that Twitter was silencing right-of-centre voices. A lot of people like having their thumb on the scales as long as the scales are weighed in their favour. When someone comes along with perhaps a bigger thumb and pushes harder on the other side of the scales, suddenly everyone cries foul! So be very, very careful about curtailing voices that you disagree with because you might not always be the ones in charge about who gets to speak and who doesn’t.

JENRICK: I don’t have a strong opinion, to be honest, on Elon Musk. I’m interested in AI but I’m not going to be booking a tête-à-tête with Elon Musk any time soon.

For Theresa May, it was running through fields of wheat; what’s the naughtiest thing you’ve ever done?

CLEVERLY: It’s all on a [BBC] interview I did with John Pienaar in 2015. [Cleverly told Pienaar he had smoked cannabis at university and watched online porn.]

JENRICK: I was actually quite naughty as a child and teenager. So a lot of the things I did probably should not enter the public domain. I’ll give you one, which, I’m afraid, is by no means the naughtiest thing I did. After a few too many drinks, as a teenager, I did accept a bet to climb the Christmas tree in Wolverhampton’s city centre. That did not end well.

BADENOCH: I don’t care to say. It definitely is not running through fields of wheat, but I’m not going to tell you the naughtiest thing I’ve ever done.

TUGENDHAT: I invaded a country once which was a few years ago, 2003; I was part of the invading army in Iraq.

Watch the Tory leadership candidates on Spectator TV:

This is an edited excerpt of the answers given to Spectator TV. To watch the full interviews go to spectator.co.uk/tv

Comments