Netflix Rules Over International Content in Hollywood, and It’s Only Getting Bigger

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 2015, a crime drama about the rise of international drug cartels, filmed in Colombia in both English and Spanish and starring Brazilian actor Wagner Moura as Pablo Escobar, seemed like a risky play for Netflix, which had only started producing original content four years earlier.

But despite the bilingual dialogue — and a mishmash of local accents that were ridiculed by Colombians — “Narcos,” with an estimated budget of $25 million, turned into a critical hit and became a cornerstone in an emerging global strategy that has made Netflix the undisputed leader overseas, both in original productions and subscribers.

While its rivals, including Disney and Warner Bros. Discovery, have taken a more deliberate road to international expansion, Netflix made early and expensive bets on overseas co-productions, and established a global foothold by launching in dozens of markets — even ones where it was difficult to break even because of lower pricing for the service.

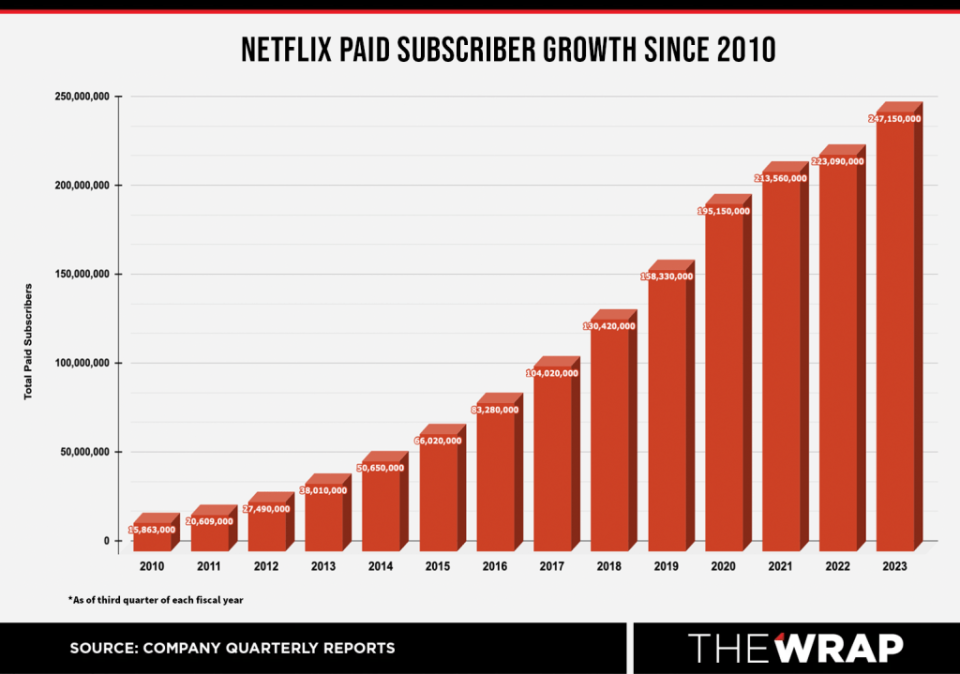

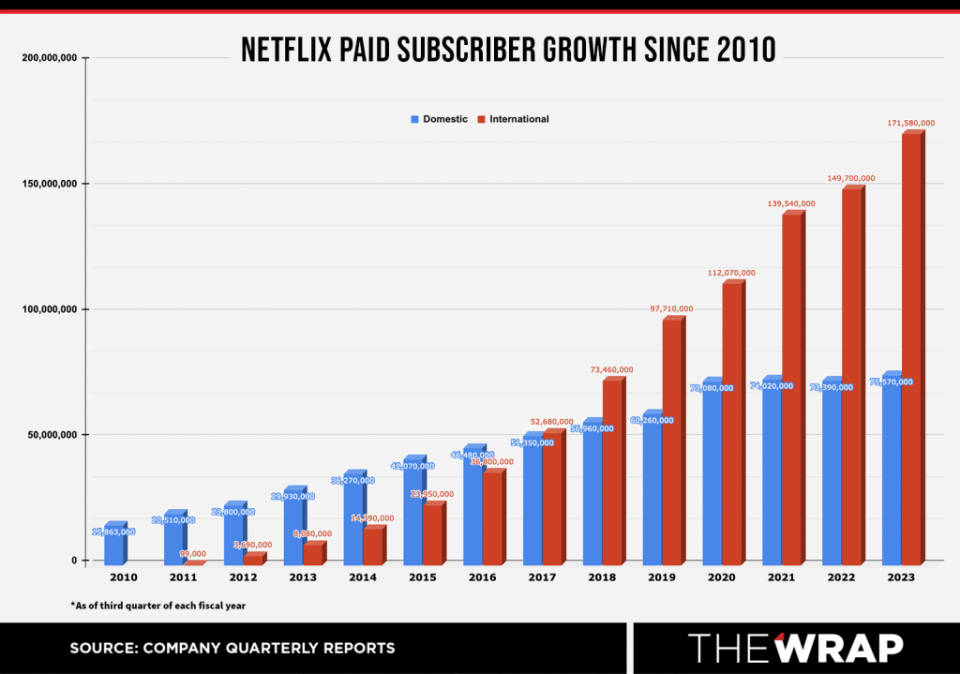

Today, thanks largely to its sweeping international bet, Netflix is not only the most profitable streamer, but also the market leader in total subscribers, with 247.15 million as of the third quarter 2023 — more than 70% of which are outside the United States. From January to June of 2023 alone, non-English language titles accounted for 30% of viewing, according to a viewership transparency report released on Tuesday.

“Without international, you can’t win this game,” Oppenheimer & Co. managing director and senior internet analyst Jason Helfstein told TheWrap. “If you want to have the most and the best content, you need to be able to monetize globally. It’s expensive to have more content unless you have a global scale.”

Before Netflix, television shows primarily found success within their own geographical bubbles. Occasional hits would trickle over from time to time — such as the UK hit “Doctor Who” in the U.S. and the NBC juggernaut “Friends” globally — but by and large, non-English language shows struggled to find an audience in the U.S.

That changed with “Narcos,” the first show where American audiences “started reading subtitles,” series director Andrés Baiz, who also directed episodes of “Narcos: Mexico,” told TheWrap. “People started just seeing shows not as being American or Colombian. It’s for the world.”

The steamer’s first exclusive international acquisition was the Norwegian drama “Lilyhammer” in 2012. And its biggest overseas hit remains the South Korean series “Squid Game,” which secured a self-reported 2.2 billion hours viewed in its first season. (The next-highest original is “Wednesday,” which has over 1.7 billion hours viewed.)

Netflix is leaning into its international advantage. The streamer, which is pulling in about 60% of its total revenues from overseas — a figure that is likely to grow over time, the company has told shareholders — plans to spend $17 billion on content in 2024, which will include more international spending, co-CEO Ted Sarandos revealed during the UBS Global Media and Communications Conference earlier this month.

The current king of global

Nearly every major network and streamer has experimented with international co-productions in recent years. CBS aired the U.K. version of “Ghosts.” HBO collaborated with Italy’s RAI and TIMvision for the Italian language “My Brilliant Friend.” And the CW has heavily invested in Canadian co-productions as of late, including “Son of a Critch” and the upcoming “Wild Cards.”

But Netflix, which is available in more than 90 countries — excluding China, Crimea, North Korea, Russia and Syria — is currently involved in projects in over 50 countries and languages. Overall, the streamer has produced or co-produced 722 international series filmed in a non-English language, by TheWrap’s count, including scripted, unscripted, docuseries and specials.

Of Netflix’s 247 million subscribers, less than one third, or 77 million, are based in the U.S. and Canada. Nearly 84 million are in Europe, the Middle East and Africa region; nearly 44 million are in Latin America; and 42 million are in Asia Pacific. (By comparison, 107.3 million of the 150.2 million total Disney+ subscribers, or 71%, are based outside the U.S. and Canada and 42.5 million of Warner Bros. Discovery’s 95.1 million subscribers, or 45%, are international.)

Netflix Co-CEO Ted Sarandos said the company’s international success has stemmed from giving decision-making power to overseas executives, rather than dictating from its global headquarters in Southern California.

“[It’s] having people on the ground running those businesses that understand the local culture, the local ecosystem, the local payment methods — all those things that really do vary country-to-country,” Sarandos said during the UBS conference. “And we’ve been able to build on that scale by investing in that international presence.”

Expanding overseas

While “Narcos” proved to be a global hit, the first bold step in Netflix’s international expansion occurred in 2010 when the company launched the service in Canada.

At the time, Netflix had 16.9 million subscribers. Within a year, Netflix moved into 43 countries and territories in Latin America, starting with Brazil and then Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile, Mexico and Colombia, and the Caribbean — marking the first time the company would be available in a language other than English — and grew to 21.4 million subscribers.

By 2013, the streamer had 27 million subscribers in the U.S. and more than 6 million subscribers in other countries, after it launched in the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Nordic countries.

In 2012, Netflix released “Lilyhammer,” a dramedy series starring “The Sopranos” actor Steven Van Zandt and filmed in English and Norwegian, which first aired on NRK1 in Norway.

Netflix doled out around $24-$25 million for the streaming rights to the first two eight-episode seasons in the U.S., Canada and Latin America, as well as second window licenses in the Nordics, the U.K. and Ireland, an insider familiar with the deal told TheWrap. Netflix renewed the show and spent another $12 million, or $1.5 million per episode, for a third and final season.

“Lilyhammer” executive producer Lasse Hallberg told TheWrap that he and Van Zandt were drawn to Netflix because it was a new platform that was already starting to create buzz overseas. That collaboration would go on to be a “dream come true,” he said.

At first, it opened doors for Hallberg, Van Zandt and “Lilyhammer” creators Anna Bjørnstad and Eilif Skodvin. On a grander scale, Hallberg said it blazed a trail for other local directors, writers and actors and foreign language content across the globe to become more internationally accessible.

“It was so easy to work with them at the time,” Hallberg said. The show “really marketed Netflix in Norway and the Nordic region and made them become the biggest streamer immediately there.”

Hallberg has since teamed up with Netflix on “Gangs of Oslo,” which was released on the platform this January.

“A good drama is a good drama if they’re speaking South Korean, Spanish or German,” Hallberg said. “Good stories travel and educate the audience, and Netflix helped them out.”

After establishing itself in the U.K. and Latin America, the streamer pushed further across Europe. Between 2013 and 2015, Netflix launched in The Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Luxembourg and Switzerland, setting up a European headquarters in Amsterdam and an office in the U.K. It also entered Japan, Cuba, Australia and New Zealand. Most of these territory expansions brought with them plans for new localized original content.

But it was 2015 that marked the shift that would later define the company. Prior to then, Netflix had only licensed international co-productions. That changed with “Club de Cuervos” (Club of Crows), Netflix’s first non-English original series filmed in Mexico. That was followed weeks later by the debut of “Narcos,” an American co-production with Gaumont International Television that blended both English and Spanish as the story called for it.

At a time when it was rare for any streaming show to receive awards attention, “Narcos” scored nominations for two Golden Globes and three Emmys in its first season. That success helped stem concerns about American audiences being thrown by its subtitles. “It became organic,” Baiz said.

“The trust and the creative freedom I get, the way that they present notes, the way they speak to the creative team, it’s never imposing,” added Baiz, who recently worked closely with Netflix on the upcoming crime drama “Griselda,” starring Sofia Vergara. “I feel at home there.”

As its content became more global, so did the company. By the end of 2016, Netflix was available in more than 190 countries and 21 languages around the world with 93.8 million members globally. That year, it premiered “The Crown,” its first-ever original drama series from the United Kingdom (Netflix spent a reported $130 million on the show’s first two seasons); “Marseille,” its first original French series; and “3%,” its first original Brazilian series. The Emmy and Golden Globe-winning “The Crown” would go on to become one of the streamer’s biggest shows to date.

By the end of 2017, Netflix had hit another major milestone: For the first time in the streamer’s history, more than half of its subscribers were based outside of the U.S. The company reported a total of 117.58 million subscribers, including 62.83 million international subscribers.

Over the next two years, Netflix would release its first originals across several languages, including the German series “Dark,” the Italian series Suburra,” and the Spanish series “Cable Girls” and “Elite.”

Dario Madrona, the co-creator of “Elite,” told TheWrap that working with Netflix has allowed him to work and travel all over the world and for co-creator Carlos Montero to start his own production company. First released in 2018, the critically acclaimed teen drama about a fictional elite high school, which is set to end after its eighth and final season, remains one of Netflix’s most-watched non-English series in the United States. Season 3 is currently the 10th most-watched non-English season on Netflix ever with over 50 million views.

“Back in the day, there hadn’t been any worldwide streaming hits yet that weren’t from the U.S.,” Madrona said. “We remember someone at Netflix telling us that workers at their [Los Angeles] HQ were passing around our screeners, talking about it around the water cooler, hooked on the show.”

Awards payoffs and production expansion

While it’s difficult to determine the success of Netflix shows and movies released prior to 2020 —the year the streamer first unveiled its Top 10 list — by 2018 evidence that the globalized strategy was working started to emerge on the awards front.

That year Netflix received an Academy Award nomination for Best International Film for the Hungarian film “On Body and Soul.” The following year Alfonso Cuarón’s “Roma” became an awards juggernaut, winning the Oscar for Best International Feature Film as well as Best Directing and Best Cinematography.

Netflix’s production started to match its globalized subscriber base and content. In 2019, the company opened production hubs in Madrid, New York, Toronto and the U.K.’s Shepperton Studios.

The next year it expanded its Paris office, as well as offices in Copenhagen, Rome and Stockholm, and Istanbul in 2021. As the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged the globe with lockdowns, Netflix was still making international history, launching its first Norwegian original series (“Ragnarok”), its first South African original series (“Queen Sono”) and its first Tamil original film (“Paava Kadhaigal”).

A “Squid Game”

In 2021, Netflix scored two major non-English hits: the French series “Lupin” and Korean series “Squid Game,” which remains Netflix’s most-watched original series of all time. Its popularity inspired a reality show spinoff, “Squid Game: The Challenge,” which has been viewed over 11.4 million times since its debut in late November. Wins like those have given the company the confidence to stay the international course.

In the first half of 2022, Netflix’s revenue growth began to slow as it suffered two consecutive quarters of subscriber declines, which it attributed to connected TV adoption, account sharing, competition and macroeconomic factors such as sluggish economic growth and the impacts of the war in Ukraine. Its subscriber troubles proved short-lived as the company began to bounce back in the second half of the year, climbing to 230.75 million paid subscribers.

The Europe, Middle East and Africa regions became the company’s largest growth areas with 76.73 million paid subscribers as of the fourth quarter of 2022, compared to 74.3 million paid subscribers in the U.S and Canada, 41.7 million paid subscribers in Latin America and 38 million in Asia-Pacific.

The pros and cons of going international

Netflix’s gamble on globalization has “mostly worked in their favor,” Wedbush Securities analyst Michael Pachter told TheWrap.

By operating outside the U.S. the streamer has been able to lower its overall production costs, expose its existing catalog to new countries and create workarounds for recent production disruptions caused by the Hollywood strikes. But offering the platform across the world has meant Netflix has had to price the service at lower levels in less-wealthy countries, hurting its average pricing. The streamer has mitigated that challenge by only providing lower-priced and catalog content in certain countries.

“International subscribers outside of high GDP areas [such as] Western Europe, Japan, Korea and Australia are generally unprofitable and require adept management to get them close to break even,” Pachter added.

And competing successfully in major markets around the world is an expensive endeavor — a risk that doesn’t always pay off. Netflix will have spent around $13 billion on content in 2023 and $17 billion in 2024. Though the company does not break out its content spend figures by region or country, it has previously pledged to invest $2.5 billion in South Korea through 2027, including for production and training initiatives and programs for local crew. It’s also on pace to invest nearly $6 billion in the United Kingdom by the end of 2023 and will spend $1 billion reais (about $200 million) on Brazilian content through 2024.

“To date, Netflix has walked the tightrope of keeping content costs in check relative to the average revenue generated per subscription,” S&P Global analyst Seth Shafer told TheWrap.

While Netflix’s competitors have struggled to catch up, Disney, Paramount and WBD also avoided some of the heavy upfront costs Netflix endured in its global expansion by being more deliberate about international markets they expand into, and by relying on distribution pacts with pay TV and telecommunications operators, Shafer said.

The future of Netflix international

Despite the challenges, the streamer has no plans to pull back on global content anytime soon. Sarandos revealed at the UBS conference that Netflix would start focusing more on local language unscripted programming initiatives, citing recent successes such as the British docuseries “Beckham” and South Korean reality show “Physical: 100.”

To bolster subscriber growth, Netflix embarked on a password-sharing crackdown for an estimated 100 million households globally, including 30 million in the United States and Canada. The company has rolled out the initiative in every region it operates in, executives disclosed during Netflix’s third quarter earnings call.

The streamer also launched a new $6.99 per month ad-supported tier, which has surpassed 15 million monthly active users globally as of the offering’s one-year anniversary on Nov. 1. Sarandos said he’s been “completely satisfied” with the ad-tier rollout, noting that it has purposely been slower to account for county-to-country nuances and regulations.

Shafer believes Netflix’s future success is “clearly linked” to how it performs overseas, including in Brazil, Mexico, the U.K., France, Germany, India and emerging Southeast Asian markets.

He touted Netflix’s ability to maintain “enviable” average revenue per user (ARPU), even in challenging markets in the Latin America and Asia-Pacific regions, as a key driver behind its sustained profitability and growing free cash flow. But continuing to maintain profitable ARPU levels, particularly in higher growth APAC markets, remains a bigger challenge for Netflix moving forward, Shafer said, which may hinge on the success of its password-sharing crackdown and the continued rollout of the ad tier.

Looking ahead, Pachter expects Netflix to slowly raise prices while continuing to focus on “low cost and highly leverageable foreign-produced content.” The streamer boosted prices in the U.K. and France in October and announced plans during its third quarter earnings call to phase out its ad-free basic plan in Germany, Spain, Japan, Mexico, Australia and Brazil.

“Netflix will ultimately be profitable everywhere,” he said.

The post Netflix Rules Over International Content in Hollywood, and It’s Only Getting Bigger appeared first on TheWrap.